On 1st July 2024, the European Union-Kenya Free Trade Agreement (known as the Economic Partnership Agreement) entered into force. EPA negotiations and agreements have been going on for the past two decades and are now so ordinary in Kenya-EU trade relations that it almost feels mundane to make a fuss of the Agreements entry into force. But in extoling the expected outcome of EPAs, the EU has triumphantly called them key milestone in EU-Kenya economic partnership. While Kenya has a varied number of trade agreements with different countries ranging from preferential trade agreements to customs union, the EPA agreements still remain perhaps the most emblematic of the country’s enthusiastic embrace of trade liberalization and acceptance of the inevitable tide of trade reciprocity between the global north and south states. Free Trade Agreements have become a tool of choice in the country’s quest for market expansion. Therefore, as the country slides further into a variety of Free Trade Agreements, it is important to pause and reflect on what the Free Trade Agreements really portend for the country’s trade creation. Have the EPAs been effective trade tools for Kenya? Have the EPA’s triggered some national principles on the logic of free trade agreements? With Whom and why?

As I argue here, the entry of the EPAs into force provides an opportunity to not only evaluate their effectiveness in market preservation for Kenya, but also to clarify the logic of free trade agreements. From a Kenyan perspective, clarity on each of the strategic objectives and owning the narrative of what the country expects from each of its free trade agreements is essential.

On trade, EPAs have delivered

| Growth in value of Kenya exports to the EU | Comparative Growth in Exports for Kenya 2018-2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | $1.16B (0.4%) | 1. | Africa | 100% | |

| 2015 | $1B (0.54%) | 2. | Asia | 31% | |

| 2010 | $814m (0.41%) | 3. | Americas | 16% | |

| 2005 | $652m (0.45%) | 4. | Middle East | 68% | |

| 2001 | $399m (0.46%) | 5. | Europe | 22% | |

As the new EPA agreement kicks off, three trends are already evident as outcomes of the whole EPA process within a broader context of global trade re-alignments. One, the Kenya-EU EPAs has delivered in preserving Kenya’s EU market as well as modest expansion of exports to the EU. As data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) shows (above), Kenya has doubled the value of its trade to the EU from $814m in 2010 to $1.16 billion in 2022. As far back as 2015 the KIPPRA Report on Implications of Economic Partnership Agreement on Kenya already correctly argued that EPA’s would mostly serve to preserve market access by Kenya in the EU and avoidance of market disruption. On that account we can then conclude that EPAs have been effective. Kenya’s European market has not only been preserved but there have been modest gains in value of exports. However, as data from the Kenya Bureau of Statistics also shows, in more recent years, expansion of Kenya’s exports to the EU is dwarfed by the growth of exports to other regions of the world (see table above).

The leading region of growth for Kenyan exports over the past 5 years has been the rest of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Thus, while EPAs have been mutually advantageous to both the EU and Kenya in market preservation, evidence on Kenya’s exports growth also suggests that the threshold of volume expansion and growth in Europe may have reached its zenith. This is further demonstrated by the decline in the percentage of Kenyan exports as a percentage of all EU imports from the peak of 0.54% in 2015 to the present 0.4%. This means that EPAs have worked but growth is elsewhere.

| Kenya exports to the EU +UK | 2008 | 2016 | 2022 | ||||

| Value | Volume | Value | Volume | Value | Volume | ||

| 1. | Tea | $0.9m | 17% | $1.28 | 13% | 1.4b | 10% |

| 2 | Cut flowers | $0.37m | 88% | $0.53 | 77% | $0.65m | 70% |

| 3. | Coffee | $179 | 70% | $218m | 51% | $341m | 51% |

The other discernable trend in Kenya-European Union trade is the gradual (and mutual) reduction of Europe’s role as Kenya’s main trade partner (as well as Kenya decline as an EU trade partner). In 2010 for example, EU accounted for 24% of Kenya’s total exports. That percentage dropped to 21% in 2015 and further down to 15% in 2023. This reduction in reliance on Europe for exports is further demonstrated by the decline in export volumes of some of Kenya’s main exports to the EU as shown above. The percentage of cut flowers, tea and coffee sold to Europe as a percentage of all exports is on the decline. Europe remains a critical trade partner. But as this EPA goes live, it’s important to pay closer attention to the global re-alignment of trade toward Asian countries as the new engines of global demand and exchange. For example, while Germany dominated Kenya’s coffee imports ten years ago, this pole position is now with the US and South Korea. Similarly, while Netherlands still accounts for the biggest share of cut flower exports (41%), Saudi Arabia (6.25%) and Kazakhstan (3%), have emerged as important growth markets. Free trade agreements for market expansion ought to be looking out to these new markets as engines of medium-term growth.

Kenyan growing food imports and the changing structure of the North’s exports

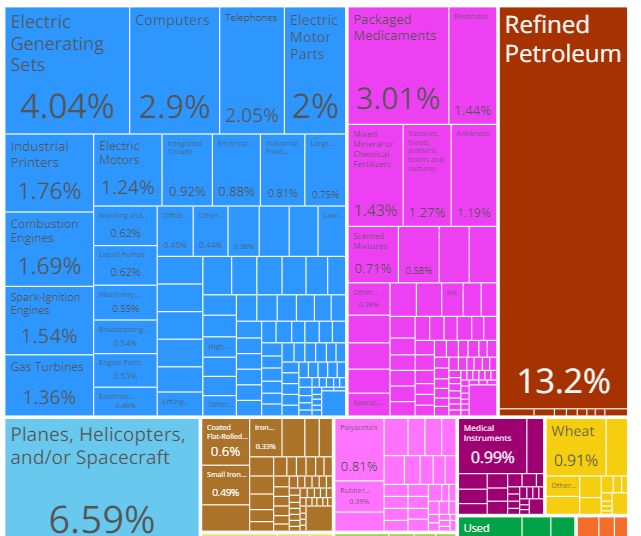

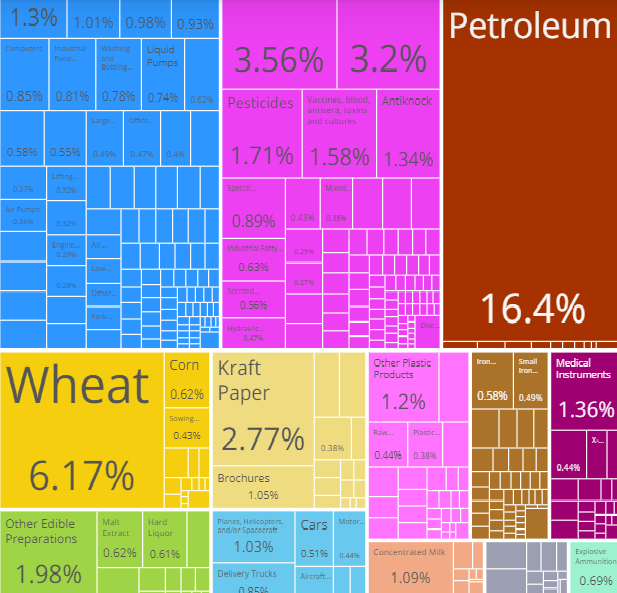

One of the remarkable qualities of the EPAs is how they represent the changing structure of the North’s industrial states exports. There was a time when in typical Prebischan terms, we would expect Europe to be selling to Africa (global South) engines and medicines while we sold them coffee, oil and tomatoes. Times are changing and Spain and France for example are now leading global exporters of tomatoes. As such over the course of the EPA agreement, Kenya-EU trade has witnessed the growing composition of Kenyan food imports from Europe. In 2010 for example, Kenya imported less than 1% of wheat from the EU. In 2022, wheat is Europe’s 2nd biggest export product to Kenya (6% of EU exports) after refined petroleum (16% of EU exports). In 2010, Kenya did not import corn (maize), animal food or edible preparations from Europe. In 2022, the country imported corn worth $12.6m, animal food worth $21.5m and edible preparations worth a whopping $40m from the EU. The trend of growing food import from Europe is of course a touchy affair for domestic producers. However, it seems that old Ricardian ideas of comparative advantage as a principle of organizing global production is hopelessly fickle. We must learn to see Europe as a formidable food producer and exporter.

| EU exports to Kenya 2010 | EU exports to Kenya 2022 |

|

|

How Kenya farming can adjust and capitalize on EPAs

There exist several potentials for Kenyan farmers in the EU- EPA arrangement. This agreement opens opportunities to expand Kenya’s foot print largely in the horticultural sector. This will be enhanced through duty free and quota free access to the EU market which is provided for in the agreement. For Kenya, her traditional exports to the EU have been vegetables, fruits, and cut flowers. For the food products, the EU through its development assistance is keen to engage in a series of capacity interventions for farmers. This includes compliance with EU standards including sanitary and phytosanitary standards (SPS). SPS are World Health Organization (WHO) health regulations that are meant to contain negative effects resulting from harmful additives, contaminants, including disease carrying organisms.

For small scale Kenyan farmers to leverage these potentials, there are several hurdles to overcome. These include inadequate financing and navigating the raft of processes to be export ready. In terms of the export process, farmers have to be in compliance with the quality and compliance of EU standards, including a phytosanitary certificate. Moreover, they have to ensure packaging and labeling compliance in line with EU regulations. It would be prudent for small scale farmers to collectively organize across cooperatives and producer groups for efficiency in the value chain process. The value chain requires several players and indeed investments like cold chains for perishable products such as vegetables and refrigerated trucks. These investments need financing that would be out of hand for individual and small scale farmers. Harnessing their synergies would help close financing gaps, but also to better enhance the compliance standards for the EU market. By organizing around groups, small scale farmers would have easy access to credit and grants, market information, and enhanced policy and regulatory compliances. In terms of regulatory compliance, being organized stimulates better coordination with key government agencies such as the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS), which among other functions is responsible for seed certification, and phytosanitary certification. Furthermore, these groups would co-share research and technology adoption costs to scale their reach and effectiveness in the EU market.

Other potentials for Kenyan farmers lie with the recent Kenya- UAE Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement that awaits ratification by parliament. This agreement in addition provides preferential market access for a series of products such as fruits, vegetables and cut flowers. To leverage on these opportunities, the Ministries of Trade, Investments and Industry, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, should engage in sensitization forums as well as putting policy interventions to expedite adaption and compliance with EPAs in the private sector. These would be critical in scaling the participation of small-and large-scale farmers in the evolving trade opportunities crucial for Kenya’s economic development.

EPAs and the logic of free trade agreements

| Country | Kenya Exports to: | Kenya Imports from: | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | $402m | $477m | Surplus – $75m |

| United Kingdom | $407m | $381m | Surplus – $26m |

| Germany | $158m | $288m | Deficit – $130m |

| United Arab Emirates | $294m | $3.6B | Massive deficit – $3.3B |

Ultimately, the utility of free trade agreements is in how well they improve a country’s trade balance towards a surplus or reducing deficits. Since EPAs have kept their bargain in holding Kenya’s European markets, what can we learn from them about who and when to get into free trade agreements? Is the United Arab Emirates for instance whose Comprehensive Economic Partnership with Kenya that was recently announced by cabinet an ideal candidate for an FTA? In my view, EPAs provide three insights into the logic of most suitable FTA partners: One, the bilateral levels of trade between the two countries should be proximal. Two, the partner country should hold palpable export potential and three; ideally, Kenya should have as broad a range of exports products to that country as possible. On all three accounts Kenya has held decently against the EU and thus EPAs have been mutually beneficial. Kenya for example holds a trade surplus against its leading export destinations in Europe (Netherlands and the UK) and a surmountable trade deficit with Germany. But while Kenya has a decent range of export products to the UAE, a potential Kenya-UAE FTA would raise questions about the likelihood of a potential FTA in narrowing down Kenya’s 3-billion-dollar trade deficit. On the other hand, in the absence of AGOA, a possible FTA with the United States makes sense as it fulfills all these three conditions superbly. And if we are to look east, I would go for Japan and India which though not ideal in condition 1- they hold massive trade surplus against Kenya, they provide greater export potential in the promise and diversity of their imports from Kenya.