1.0 Introduction

The Greater Eastern Africa continues to face persistent challenges from violent extremism, governance gaps, and fragile security environments, posing serious risks to peace, stability, and development in the region. Extremist groups such as Al‑Shabaab remain operationally capable and lethal, conducting high-impact attacks and exploiting socio‑economic vulnerabilities. In March 2025, Somali security forces ended a 24-hour siege by al-Shabaab militants at the Cairo Hotel in Beledweyne, highlighting the group’s ability to target strategic locales and civilian gatherings (Associated Press, 2025). In the same month, Al‑Shabaab militants raided a Kenyan police reservist camp near the Somalia border in Garissa County, killing six officers and seizing weapons, underscoring persistent spillover dynamics in cross-border regions (AP News, 2025). Regionally, reported data shows a sharp increase in violent extremist incidents and fatalities across the Horn of Africa in early 2025, driven by intensified attacks and retaliatory operations (IGAD report as cited in Eastleigh Voice, 2025). While some recent reports suggest a modest decline in fatalities later in 2025, militant groups are adapting their tactics, including the use of drones, crypto‑financing, and cross-border strikes, demonstrating resilience amidst counter‑efforts (Eastleigh Voice, 2025).

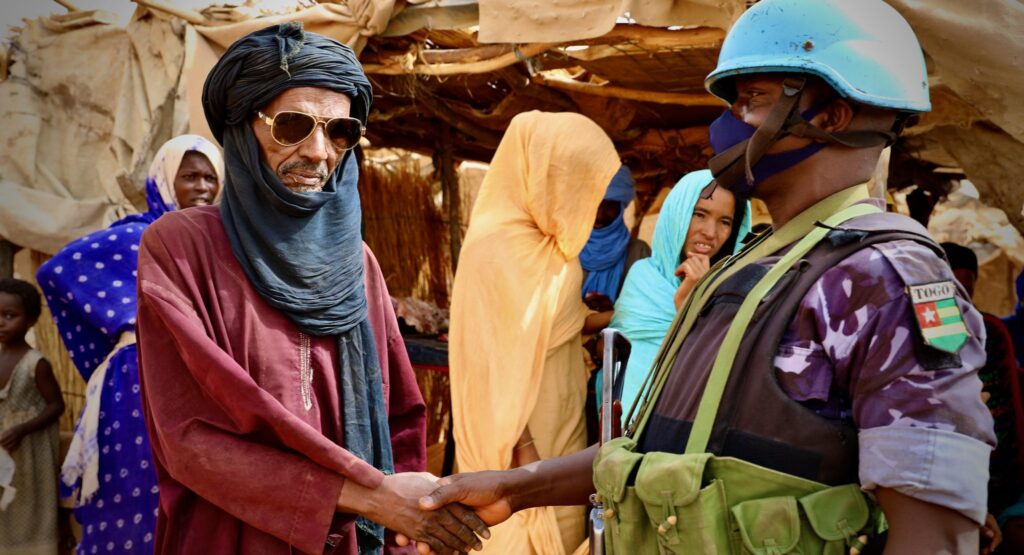

To counter this vice,regional and international cooperation mechanisms are expanding. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) continues to strengthen joint counter-violent extremism coordination and intelligence sharing, and partner states are enhancing operational cooperation. However, extremist networks continue to exploit socio‑economic grievances, youth unemployment, weak governance, and porous borderlands to sustain recruitment and extend influence. This commentary focuses on structural drivers of violent extremism in the Greater Eastern Africa countries and offers targeted policy recommendations designed to strengthen resilience and guide actionable interventions.

2.0 Key Issues

2.1 Active Violent Extremist Actors

Violent extremist actors in Greater Eastern Africa remain highly adaptive and lethal. In March 2025, al‑Shabaab attacked a Kenyan police reservist camp in Garissa County, killing six officers and seizing weapons, illustrating sustained cross-border capability (Associated Press, 2025). In October 2025, militants assaulted Godka Jilaow prison in Mogadishu, causing multiple casualties before being neutralised (IGAD, 2025). Al‑Shabaab continues attacks in Somalia and Kenya while exploiting weak governance and security gaps in Ethiopia and Uganda. The Islamic State–Somalia Province (ISSP) operates in Puntland and northern Somalia, using mountainous terrain for training and planning cross-border raids (Eastleigh Voice, 2025). Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and smaller ISIS-aligned cells in Kenya, Tanzania, and DRC maintain regional networks, facilitating recruitment, logistics, and financing. These groups leverage global jihadist ideologies, local grievances, and cross-border mobility to undermine state authority and social cohesion. Persistent extremist activity demonstrates the need for intelligence-driven, coordinated operations with regional partners, integrating tactical responses and community engagement to limit recruitment, disrupt operations, and strengthen border and national security.

2.2 Youth Unemployment and Economic Marginalisation

Youth unemployment in Greater Eastern Africa is a key driver of extremist recruitment. In 2025, over 60% of the IGAD region’s population was under 25 years, with most lacking formal employment opportunities (IGAD, 2025). In Kenya’s north eastern counties, limited jobs, poor infrastructure, and chronic underdevelopment have facilitated repeated Al‑Shabaab attacks targeting young recruits from Garissa and Wajir Counties(Associated Press, 2025). Extremist groups exploit economic vulnerability, offering income, social recognition, and ideological belonging. In Somalia, Puntland’s underdeveloped districts report youth participation in ISSP-linked activities due to a lack of vocational training and livelihood support (Eastleigh Voice, 2025). Without short-term cash transfers, apprenticeships, and digital skills programs, and long-term support in entrepreneurship, microfinance, and job creation, young people remain highly susceptible. Coordinated interventions between governments, civil society, and private sector actors are essential to provide immediate income support, expand skills, and integrate youth into productive economic roles. Addressing youth marginalisation not only reduces recruitment but also strengthens community resilience and contributes to regional stability across Greater Eastern Africa.

2.3 Governance Deficit and Political Exclusion

Weak governance and political exclusion in Greater Eastern Africa’s borderlands and peripheral regions increases vulnerability to violent extremism. In Somalia, ongoing insurgencies in Galmudug and Jubaland limit federal government service delivery, leaving communities dependent on informal authorities (IGAD, 2025). In Kenya’s north eastern counties, perceptions of elite capture and corruption reduce citizen trust, creating fertile ground for Al‑Shabaab recruitment among disaffected youth (Associated Press, 2025). In Uganda and Tanzania, local populations report limited participation in decision-making and uneven resource allocation, which extremists exploit to gain legitimacy. Lack of transparency, accountability, and grievance redress mechanisms undermines institutional credibility and civic engagement (Eastleigh Voice, 2025). Strengthening participatory governance, including community councils, consultative platforms, and anti-corruption measures, is essential to rebuilding trust. Inclusive political processes and equitable service delivery reduce grievances that extremist actors manipulate. By fostering accountability, transparency, and local involvement, states can limit radicalisation, increase community resilience, and reinforce social cohesion, providing a foundation for sustainable security and development across Greater Eastern Africa.

2.4 Porous Borderlands and Regional Security Gaps

Porous borders across Greater Eastern Africa continue to enable the movement of militia fighters, weapons, and illicit financing, facilitating extremist operations. In 2025, repeated incursions by Al‑Shabaab militants occurred along the Kenya–Somalia border in Mandera, Wajir, and Garissa counties, including ambushes and kidnappings targeting security personnel and civilians (Associated Press, 2025; OSAC, 2025). Militants exploit weak coordination between national security agencies, limited intelligence sharing, and uneven border patrol coverage, allowing cross-border mobility and recruitment. In northern Somalia, ISSP and allied cells have used remote, lightly governed districts for training, logistics, and planning attacks on both Somali and Kenyan territories (Eastleigh Voice, 2025). IGAD and regional partners have called for integrated border management, joint patrols, and real-time information sharing, yet gaps remain in enforcement and community engagement. Strengthening cross-border security architecture, investing in technical capacity for monitoring, and empowering local communities to report suspicious activities are critical. Effective collaboration and surveillance reduce extremist mobility, disrupt financing, and enhance stability across borderlands in Greater Eastern Africa.

3.0 Conclusion

Violent extremism in Greater Eastern Africa persists due to active extremist groups, youth marginalisation, weak governance, and porous borders. Intelligence services, police counterterrorism units, and defence forces must conduct coordinated operations to disrupt extremist networks. Labour, youth, and education authorities, alongside microfinance institutions and private-sector partners, must expand employment and skills programmes for at-risk youth. Interior ministries, local governments, and anti-corruption agencies must strengthen inclusive governance and equitable service delivery. Border security agencies, immigration, and customs authorities, together with regional platforms, must implement integrated border management. Coordinated action, accountability, and monitoring across these sectors will reduce extremist recruitment, enhance social cohesion, and stabilise vulnerable communities.

4.0 Policy Recommendations

4.1 Countering Active Violent Extremist Actors

National intelligence agencies, police counterterrorism units, and defence forces in the Greater Eastern Africa must conduct coordinated operations against Al‑Shabaab, ISSP, and affiliated networks. Interior ministries should deploy cross-border rapid-response teams along high-risk corridors in northeastern Kenya, Puntland, and Galmudug to interdict fighters, weapons, and financing. Security agencies must implement real-time intelligence sharing, joint threat assessments, and integrated operational planning. Local authorities and community leaders should establish early-warning systems for suspicious activities. Rehabilitation programs for defectors must expand with community-based reintegration. Oversight bodies must enforce civilian protection standards. Interagency coordination, clear leadership, and performance monitoring with strict timelines ensure measurable outcomes. Combining tactical counterterrorism with community engagement disrupts extremist planning, limits recruitment, strengthens public confidence in security institutions, and stabilises vulnerable regions. These steps provide a practical framework to neutralise threats while maintaining trust and resilience in affected communities.

4.2 Reducing Youth Unemployment and Poverty

Youth in Greater Eastern Africa are highly vulnerable to extremist recruitment due to unemployment and economic marginalisation. Governments and relevant authorities must implement targeted employment programs in high-risk areas, including north eastern Kenya, Puntland, and borderland districts in Uganda and Tanzania. Vocational training centres, digital skills initiatives, and apprenticeships should focus on market-relevant skills. Short-term interventions, such as cash transfers and job placements, must complement long-term programs supporting entrepreneurship, microfinance, and small business development. The private sector should be incentivised to create inclusive value chains and employment opportunities for youth. Local leaders and community groups must engage young people in civic activities, mentorship, and social programs to strengthen belonging and resilience. Coordinated efforts across education, labour, finance, and social services reduce susceptibility to extremist narratives, empower youth economically, and contribute to social stability.

4.3 Strengthening Governance and Political Inclusion

Interior ministries and decentralised local governments must institutionalise inclusive governance in marginalised and borderland regions. County and municipal administrations must establish consultative councils, participatory planning, and accessible grievance-redress mechanisms. Anti-corruption agencies must enforce transparency, audit compliance, and address elite capture. Line ministries must prioritise equitable delivery of security, education, health, water, and infrastructure services. Religious, traditional, and community leaders must be engaged in civic education, mediation, and social cohesion initiatives. Performance contracts, service-delivery benchmarks, citizen-feedback mechanisms, and independent audits must ensure sustained governance reform. These measures reduce grievances, limit extremist influence, rebuild institutional legitimacy, strengthen civic trust, and create accountable, responsive local administrations capable of supporting long-term peace and stability.

4.4 Securing Porous Borderlands

Border security agencies, immigration services, customs authorities, and coast guards must implement integrated border management across land and maritime corridors. Joint patrols, command centres, and interoperable communications must support real-time coordinated operations. Intelligence units must share watchlists, risk assessments, and movement data immediately. Community policing units must formalise surveillance networks involving traders, pastoralists, transport workers, and fishing communities. Training academies must upgrade operational skills, readiness, and accountability. Infrastructure authorities must provide posts, sensors, vessels, and mobility equipment. Regional coordination platforms through EAC and IGAD must synchronise operations, exercises, procurement, and maintenance. Funding, timelines, oversight, and performance reporting ensures sustainability and convert borderlands from permissive spaces into stabilising security zones that prevent extremist movement and illicit flows.

5.0 References

Alio, I. (2025). Framing jihad and marginalisation: A critical discourse analysis of Al-Shabaab’s recruitment propaganda in Greater Eastern Africa. Edition Consortium Journal of Literature and Linguistic Studies, 7(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.51317/ecjlls.v7i1.600

Associated Press. (2025, March). Al-Shabaab militants end 24-hour siege at Cairo Hotel in Beledweyne. Associated Press.

Associated Press. (2025, March). Six Kenyan police reservists killed in al-Shabaab raid near Somalia border. Associated Press.

AP News. (2025, March). Al-Shabaab militants raid a police reservist camp in Garissa County. AP News.

Barno, R., & Kamotho, J. (2025). Understanding terrorism in East Africa. In Palgrave handbook of terrorism in Africa (pp. 133–155). Springer Nature Switzerland.

East African Community. (2024). EAC calls for cross-border cooperation to counter terrorism and transnational organised crime. https://www.eac.int/press-releases/154-peace-security/3005-eac-calls-for-cross-border-cooperation-to-counter-terrorism-and-transnational-organised-crime

Eastleigh Voice. (2025). Rising violent extremist incidents and adaptive tactics in the Horn of Africa. Eastleigh Voice.

Intergovernmental Authority on Development. (2025). Regional security situation report: Violent extremism trends in the Horn of Africa. IGAD Secretariat.

Overseas Security Advisory Council. (2025). Kenya 2025 crime and safety report. U.S. Department of State.

Security Council Report. (2025). Counter-terrorism: Briefing on the Secretary-General’s strategic-level report on ISIL/Da’esh. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2025/08/counter-terrorism-briefing-on-the-secretary-generals-strategic-level-report-on-isil-daesh-9.php

United Nations Security Council. (2025). Resolution 2776 (2025). https://docs.un.org/en/S/RES/2776(2025)

United Nations Security Council. (2025). Letter dated 21 July 2025 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council (S/2025/482). https://docs.un.org/en/S/2025/482