1.0 Introduction

Corruption is a complex problem that faces the world today. Although scholars do not agree on how to define it, it is generally viewed as “…the abuse of public office for private gain (Alfano, Baraldi, & Cantabene, 2020). Current security scholarship frames corruption as a governance and development issue, ignoring its profound implications for peace and security (Chayes, 2015). This makes security policymakers treat it as a secondary concern, despite its centrality in fueling armed conflict, driving instability and organized crime, undermining peace and security agendas, and post-conflict recovery in many countries. Globally, corruption undermines national security by eroding institutional resilience, enabling illicit flows, and hollowing out the rule of law (Chipkin et al, 2018). The defence and security sectors are particularly vulnerable, where opaque procurement deals, patronage networks, and illicit arms transfers undermine global security efforts. Nowhere is this more evident than in Eastern Africa, a region that has a few countries still grappling with protracted conflicts, fragile statehood, and weak institutions. This commentary explores corruption in the defence and security sector as a key driver of insecurity within the Eastern Africa region and argues that the status of corruption and security in this region is a case study as to why anti-corruption efforts should be central to peacebuilding globally. By drawing on secondary research and case studies from Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Sudan, the author makes a case for embedding anticorruption policies in security sector reforms, strengthening oversight, and treating corruption as a core driver of insecurity which should be tackled as a priority if institutional resilience and the rule of law in Eastern Africa is to be achieved.

2.0 Key Issues

2.1 Corruption as a Catalyst of Armed Conflict

Studies show that corruption is a key driver of armed conflict and provides fertile ground for armed groups to flourish by weakening state legitimacy and diverting resources meant for public service delivery (Grindle, 2017). In South Sudan, systemic embezzlement of oil revenues and military procurement funds has not only enriched elites but also fueled cycles of violence (Mutsvairo & Kalinga, 2022). Research by Transparency International (2023) shows that billions of dollars have been siphoned away from state coffers, leaving communities impoverished and reliant on armed factions for survival. The gender impact of this situation, particularly on women, has been dire (Transparency International, 2023). Similarly, in Somalia, corruption within the security sector has hampered stabilization. Ghost soldiers, whose salaries are pocketed by commanders, drain resources while leaving frontlines undermanned against Al-Shabaab (Kubbe, Hogic & Siegel, 2025). Such practices weaken trust in government and embolden extremist groups.

2.2 Organized Crime and Illicit Economies

Currently, corruption is at the centre of illicit arms flows that remain a central driver of insecurity across Eastern Africa, due to weak oversight of arms procurement, coupled with opaque global arms trade practices (Kubbe, Hogic & Siegel, 2025). In Uganda and Kenya, investigations reveal diversion of state-owned arms into black markets, where they reach militias and criminal gangs (Tangri & Mwenda, 2013). In Sudan, years of opaque arms deals with foreign suppliers facilitated human rights abuses in Darfur (Gasiano, 2020). Defence corruption is not merely a governance issue but a direct driver of insecurity and institutional fragility. Inflated contracts, diversion of operational funds, and patronage weaken effectiveness. In Burundi, procurement scandals deepened divisions in the armed forces (Onu & Ngwube, 2024). In Ethiopia, the Tigray conflict illustrates how opaque spending undermines resilience (Mutsvairo & Kalinga, 2022). This cycle destabilizes communities and fuels violence.

2.3 Corruption is a threat to Post-Conflict Peacebuilding Initiatives

Corruption derails peacebuilding by weakening reconstruction, disempowering institutions, and fostering grievances. In Rwanda, while post-genocide recovery is notable, concerns remain about elite capture of resources and restrictions on oversight (Gasiano, 2020). In South Sudan and Somalia, aid intended for rebuilding has often been diverted by corrupt elites, prolonging fragility and undermining donor confidence (Onu & Ngwube, 2024). When peace dividends are siphoned, communities lose trust in law, creating opportunities for violent actors. Corruption corrodes governance integrity, undermines social justice, and obstructs sustainable development. In Tanzania, controversies around extractive industries highlight how corruption deprives citizens of resource benefits, exacerbating inequality (Gasiano, 2020). Patronage networks erode resilience. Citizens who perceive security forces and political elites as self-serving lose trust, leaving states vulnerable to instability. Thus, corruption obstructs both recovery and development, perpetuating fragility across the region.

2.4 Global Arms Trade and Eastern Africa’s Vulnerability

The global arms trade, marked by secrecy and weak oversight, amplifies Eastern Africa’s vulnerability (Kubbe, Hogic & Siegel, 2025). Suppliers exploit opaque procurement systems, offering bribes and kickbacks that lock states into unnecessary contracts. Kenya has faced scandals where inflated arms deals deprived the state of resources and weakened security readiness (Gasiano, 2020). This nexus between arms dealers and local elites perpetuates corruption, undermining rights and fueling conflict. Lack of transparency in transfers, combined with limited civil society oversight, makes reform urgent. Such practices entrench authoritarianism, weaken accountability, and destabilize institutions. By exploiting weak procurement systems, global actors collude with elites, sustaining cycles of insecurity. Without transparency, military corruption will remain entrenched, diverting scarce resources from development priorities. This nexus shows corruption’s dual domestic and international dimensions, requiring coordinated responses that integrate anti-corruption with peace and security agendas.

3.0 Conclusion

Corruption in Eastern Africa is not a peripheral governance issue but a central driver of insecurity. By fueling conflict, enabling organized crime, facilitating illicit arms flows, and undermining peacebuilding, corruption threatens security, institutional resilience, and the rule of law. Defence corruption should be treated as a security threat, not an administrative concern. Peace and security agendas must embed anti-corruption in reforms, prevention, and reconstruction. Transparency in arms transfers, civil society oversight, and regional cooperation will disrupt entrenched corruption networks. Tackling corruption safeguards peace, advances justice, and ensures sustainable development. Although countries differ in progress, coordinated regional efforts are essential to avoid spirals of fragility. Embedding anti-corruption in security frameworks is critical for resilience and stability.

4.0 Policy Recommendations

4.1 Disrupt Illicit Economies through Anti-corruption and Oversight

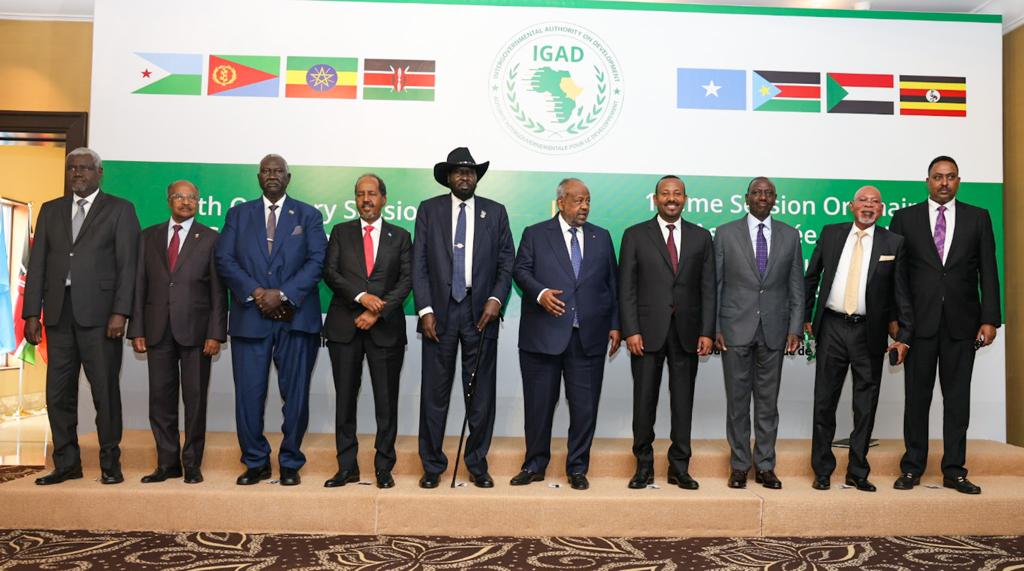

Addressing corruption as a conflict driver requires embedding anticorruption into peacebuilding efforts. Eastern African governments should institutionalize transparent defence procurement and create oversight mechanisms to monitor payroll systems, preventing ghost soldiers. Regional actors such as IGAD and AU must frame corruption as a direct threat to peace and demand accountability from member states. International donors should condition aid on transparency benchmarks, ensuring resources reach communities. Women’s participation should be prioritized in security reforms, recognizing their disproportionate vulnerability. Finally, whistleblower protections are essential to safeguard those exposing corruption. These measures will not only deter embezzlement and elite capture but also strengthen legitimacy, weaken armed factions’ recruitment strategies, and restore citizens’ confidence in post-conflict governance and peace processes.

4.2 Strengthen Measures to Curb Organized Crime and Corruption

To combat organized crime linked to corruption, Eastern Africa must strengthen border management and establish joint regional task forces to disrupt illicit networks. Governments should ratify and implement the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), enhancing transparency in procurement and preventing diversion of arms. Civil society and the media must be empowered to monitor defence spending and expose collusion between officials and syndicates. International partners should provide technical support to track narcotics and arms flows through ports such as Mombasa. Parliamentary oversight of security budgets must be enhanced to block patronage and mismanagement. Integrating anti-corruption into organized crime prevention policies will safeguard resources, reduce illicit economies, and weaken insurgent groups’ recruitment and financing capacities.

4.3 Address Corruption Risks in Post-Conflict Recovery

Addressing corruption in post-conflict settings requires donor coordination and strict monitoring of aid disbursement to prevent elite diversion. Governments should establish transparent resource allocation systems that guarantee equitable distribution of peace dividends, including health, education, and livelihoods. Strengthening community oversight through civil society participation ensures accountability in recovery projects. Regional organizations like AU and IGAD must support inclusive governance frameworks to reduce inequalities that fuel instability. Establishing independent anti-corruption commissions with prosecutorial powers will deter patronage in reconstruction processes. Ultimately, tackling corruption in peacebuilding enhances trust in governance, promotes reconciliation, and fosters stability. Embedding anti-corruption safeguards in donor programs is essential to restore legitimacy, prevent grievances, and sustain long-term institutional resilience in fragile states.

4.4 Implement Frameworks for Transparency and Accountability in the Global Arms Trade

To reduce vulnerability from global arms trade corruption, Eastern African states should adopt strict transparency measures for defence procurement, ensuring contracts are publicly disclosed and subject to audit. Governments should strengthen parliamentary committees on defence to review all arms deals, reducing secrecy. Joining international regimes such as the UN Register of Conventional Arms promotes accountability. Civil society oversight mechanisms must be protected to expose corrupt deals without fear of reprisals. At the regional level, IGAD should create an arms monitoring body to track transfers and prevent diversions to non-state actors. International suppliers should also be held accountable under anti-corruption clauses. These measures will safeguard resources, strengthen military effectiveness, and reduce cycles of fragility caused by corruption.

5.0 References

Alfano, M. R., Baraldi, A. L., & Cantabene, C. (2020). The Effect of Fiscal Decentralization on Corruption: A Non-Linear Hypothesis. German Economic Review, 20(1), 105-128. doi:10.1111/geer.12164

Chayes, S. (2015). Thieves of state: Why corruption threatens global security. WW Norton & Company.

Chipkin, I., Swilling, M., Bhorat, H., Qobo, M., Duma, S., Mondi, L., Peter, C., Buthelezi, M., & Friedenstein, H. (2018). Shadow State: The Politics of State Capture. Wits University Press.

Gasiano, B. (2020). The Revival of the East African Community: Challenges and Prospects. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14(2), 310–328.

Grindle, M. S. (2017). Good governance, RIP: A critique and an alternative. Governance, 30(1), 17–22.

Kubbe, I., Hogic, N., & Siegel, J. (2025). The Ghost Soldier Trap: How Corruption Undermines Security and Stability. Working Paper Series.

Mutsvairo, B., & Kalinga, O. (2022). Corruption, governance, and security in Africa: Rethinking accountability. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 16(2), 243–260.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2022.2043125

Onu, G., & Ngwube, A. (2024). Political Leadership, Corruption, and Development in Burundi. African Renaissance.

https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-aa_afren_v2024_nsi2_a7

Tangri, R., & Mwenda, A. (2013). The Politics of Elite Corruption in Africa: Uganda in Comparative African Perspective. Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203626474

Transparency International. (2023). Corruption Perceptions Index.

https://www.transparency.org