1.0 Introduction

Tensions between Kenya and Tanzania escalated in mid-2025 after Tanzanian authorities imposed stringent restrictions on Kenyan traders and transporters operating in border towns such as Namanga and Arusha. These restrictions, which included the denial of business permits and tighter enforcement of territorial licensing rules, reignited long-standing concerns about protectionism within the East African Community (EAC) (Business Daily, 2025). Kenyan officials and business associations have strongly criticized these actions, arguing that they violate the principles of the EAC Common Market Protocol (EAC, 2010). The Tanzanian government has justified the latest restrictions as efforts to enforce licensing regulations and protect local enterprises from unregulated foreign competition. However, critics argue that the pattern of such measures reflects a broader protectionist turn that undermines regional cooperation.

The timing of these tensions coincided with a significant deepening of Kenya’s bilateral relations with Uganda. In July 2025, the two countries signed a series of memoranda covering trade, transport, mining, and agriculture, reflecting a strategic pivot toward coordinated state-to-state partnerships (Plus News, 2025). Against this backdrop, Tanzania’s restrictive stance appears increasingly out of sync with regional integration objectives. This commentary explores four key issues: the resurgence of protectionist trade measures by Tanzania, the EAC’s institutional weaknesses in enforcing common market commitments, Kenya’s evolving bilateralism with Uganda, and the risks of fragmentation posed by corridor competition. While Kenya’s frustration has been vocal, Tanzania has defended its actions as regulatory enforcement to protect local industries and uphold national laws. Together, these developments reveal deeper structural cracks in East Africa’s integration agenda.

2.0 Key Issues

2.1. Tanzania’s Protectionist Policies and Regulatory Retrenchment

Tanzania has increasingly pursued inward-looking trade policies that strain its relationship with regional partners, particularly Kenya. In 2021, Tanzania authorities blocked maize imports from Kenya, citing health risks due to aflatoxins.(Adano,2021) In early 2024, Tanzania suspended Kenya Airways flights in response to the denial of air cargo rights for Air Tanzania (Owere, 2024). Most recently, in 2025, Kenyan traders operating in Tanzanian border towns such as Namanga and Arusha faced permit denials and forced closures, triggering diplomatic protests from Nairobi. (Business Daily, 2025). In 2025 alone, over 200 Kenyan traders operating in Namanga reported being denied licenses, according to the Kenya National Chamber of Commerce and Industry. The Kenya Transporters Association also noted a 17 percent decline in cross-border haulage to Tanzania compared to the previous year. Although the Tanzanian government defends these measures as necessary to uphold public safety, protect domestic industries, and enforce national licensing frameworks, the recurrence of unilateral trade restrictions points to a broader trend of regulatory retrenchment. Tanzania has publicly stated that these steps are critical for managing unregulated cross-border trade, enforcing quality standards, and safeguarding local economic interests, particularly in sectors vulnerable to informal competition. However, these justifications continue to raise regional concerns over consistency with EAC integration principles.

2.2. Inadequate Enforcement of EAC Protocols and Institutional Weakness

The persistence of trade disputes within the EAC reflects a deeper institutional weakness in enforcing regional commitments. While member states have ratified key integration frameworks such as the Customs Union and the Common Market Protocol, implementation remains inconsistent and politically contingent. In theory, these protocols guarantee the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people across borders. In practice, enforcement has been undermined by limited institutional capacity and divergent national priorities. The East African Court of Justice (EACJ), mandated to interpret the EAC Treaty, lacks jurisdiction over complex economic disputes unless explicitly referred by the Summit or Council of Ministers. Its rulings are often seen as advisory rather than binding, and compliance is voluntary in practice (Apiko, 2017). Meanwhile, the EAC Secretariat, which is tasked with coordinating integration efforts, operates without executive authority to sanction non-compliant states. This creates a permissive environment in which states can impose non-tariff barriers, restrict market access, or flout trade rules with minimal consequences. Efforts to resolve disputes typically rely on ad hoc diplomatic negotiations, which are slow, non-transparent, and susceptible to political bargaining. These limitations disproportionately affect informal traders and small and medium-sized enterprises that depend on predictable regulatory environments to operate across borders.

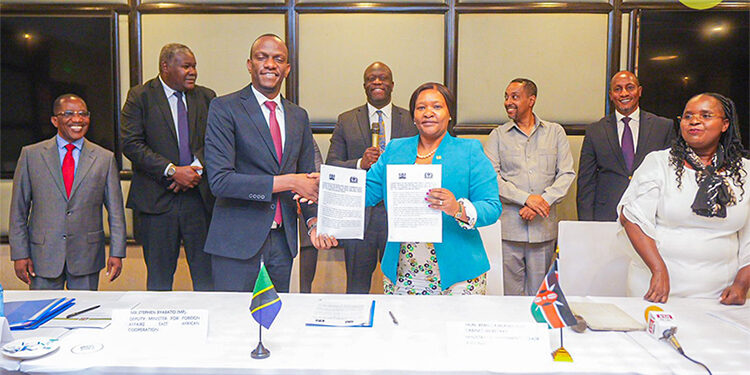

2.3. Kenya’s Deepening Economic Ties with Uganda

In contrast to its increasingly strained trade relationship with Tanzania, Kenya has deepened its bilateral cooperation with Uganda, signaling a shift toward pragmatic regionalism. In July 2025, Presidents William Ruto and Yoweri Museveni signed eight memoranda of understanding covering transport, mining, energy, standards harmonization, and agriculture (The East African, 2025)). These agreements reflect a shared commitment to predictable cross-border trade, infrastructure alignment, and regional value chain development. Transport and energy infrastructure have become key pillars of this partnership. Uganda secured USD 800 million from the Islamic Development Bank to construct a railway linking Kampala to Malaba, complementing Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) extension from Naivasha (Reuters, 2025). This integrated rail corridor is expected to accelerate cargo movement from the port of Mombasa into the interior of East Africa, reducing transit costs and delays. Simultaneously, projects such as the Bujagali–Tororo–Lessos power line have strengthened electricity interconnection and regional energy security. These developments mark a shift toward bilateral instruments as a fallback strategy in the face of EAC-wide implementation gaps. While bilateralism can enhance agility and responsiveness, it also risks entrenching asymmetries and undermining the multilateral foundations of the EAC. Kenya and Uganda’s alignment offers short-term efficiencies but could widen divergence if other member states, notably Tanzania, pursue parallel paths. The challenge for the EAC is to ensure that such bilateral momentum reinforces rather than replaces collective integration goals.

2.4. Corridor Competition and the Risk of Regional Fragmentation

East Africa’s trade architecture is increasingly shaped by competing national infrastructure strategies rather than coordinated regional planning. Kenya has prioritized the development of the Northern Corridor, anchored by the port of Mombasa and supported through investments in the Standard Gauge Railway, upgraded road networks, and inland logistics hubs. This corridor facilitates cargo flows to landlocked countries including Uganda, South Sudan, and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Its competitiveness has been further reinforced by Kenya’s recent infrastructure agreements with Uganda.

According to the Northern Corridor Transport Observatory, as of 2018, Kenya accounted for approximately 67 percent of containerized traffic through Mombasa, while transit trade to neighboring countries such as Uganda and Rwanda constituted around 32 percent. These volumes have grown steadily in recent years, supported by improved corridor performance, reduced transport time, and streamlined customs procedures. In comparison, Tanzania’s Central Corridor, which links the port of Dar es Salaam to Rwanda, Burundi, western Uganda, and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, has faced persistent challenges. While institutional coordination under the Central Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency has improved, the corridor continues to struggle with infrastructure bottlenecks, inconsistent regulatory frameworks, and limited financing. Projects such as the Isaka-Kigali Standard Gauge Railway have been repeatedly delayed, and investor confidence in long-term returns remains subdued. Although the corridor spans over 2,700 kilometers and serves key regional markets, its competitiveness remains lower than the Northern Corridor due to slower cargo movement and limited intermodal linkages. The lack of a joint corridor governance framework among EAC member states has led to duplicated investments, competing cargo routes, and inefficiencies in regional connectivity. Instead of developing complementary corridors that reinforce interdependence and scale, states are increasingly pursuing rival infrastructure projects driven by national interests. This divergence not only undermines regional economies of scale but also weakens the bloc’s collective bargaining power in global trade.

3.0 Policy Recommendations

3.1 Develop Binding Regional Guidelines to Deter Protectionism

The EAC should establish a framework that clearly defines and restricts unilateral trade actions by member states. This framework should include criteria for invoking trade restrictions, mechanisms for consultation before enforcement, and provisions for independent review. By promoting transparency and accountability, such guidelines would help restore trust among partner states and reduce the recurrence of politically motivated protectionist measures.

3.2 Strengthen the Enforcement Capacity of EAC Institutions

The mandate of the EACJ should be expanded through treaty reform to grant direct jurisdiction over economic and trade disputes, allowing private sector actors and traders to file complaints without requiring referral by state organs. The EAC Secretariat should host a dedicated Trade Compliance Unit with investigative powers and public reporting functions. Further, a peer review mechanism, modeled on the African Peer Review Mechanism, could help monitor national adherence to integration principles.

3.3 Align Bilateral Partnerships with Regional Objectives

Bilateral agreements between member states, such as the Kenya–Uganda infrastructure accords, should be formally reported to the EAC Council of Ministers and assessed for consistency with regional plans. This approach would allow countries to pursue pragmatic cooperation while ensuring that bilateralism complements rather than undermines multilateral integration efforts.

3.4 Establish a Corridor Coordination Mechanism

The EAC should create a regional mechanism to coordinate the development of trade corridors. This body would oversee planning, financing, and policy harmonization across key routes such as the Northern and Central Corridors. Coordinated infrastructure investments would reduce duplication, promote efficient cargo movement, and strengthen the region’s collective competitiveness in global trade.

4.0 Conclusion

The ongoing trade tensions between Tanzania and Kenya reflect deeper structural vulnerabilities in East Africa’s integration project. Tanzania’s protectionist turn and regulatory assertiveness suggest a retreat from the cooperative spirit of the Common Market Protocol. In contrast, Kenya’s bilateral realignment with Uganda signals a growing preference for more predictable and mutually beneficial partnerships, even if they occur outside formal regional mechanisms. These developments highlight a critical inflection point for the East African Community. The institutional limitations of the EAC, including weak enforcement capacity and limited dispute resolution authority, continue to undermine the implementation of agreed frameworks. At the same time, fragmented infrastructure planning and corridor competition risk entrenching parallel economic blocs within the region. To preserve the vision of an integrated, rules-based regional economy, the EAC must reassert its relevance. This will require strengthening institutional authority, improving compliance mechanisms, and ensuring that bilateral cooperation remains anchored in shared regional goals. In the absence of urgent reforms, the current trajectory may lead to deeper fragmentation, eroded trust, and missed opportunities for inclusive growth and collective resilience.

5.0 References

Adano, W. (2021, July 15). Why maize is causing trade tensions between Kenya and its neighbours. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-maize-is-causing-trade-tensions-between-kenya-and-its-neighbours-156797

Apiko, P. (2017). Understanding the East African Court of Justice: The hard road to independent institutions and human rights jurisdiction (Background paper, Political Economy Dynamics of Regional Organisations).

European Centre for Development Policy Management.

https://ecdpm.org/application/files/4916/6487/2178/PEDRO-Paper-13-EACJ-Apiko-December-2017.pdf

Business Daily. (2025). Kenyan traders decry permit denials at Tanzania border posts. Business Daily.

East African Community. (2010). Protocol on the establishment of the East African Community Common Market. Arusha: EAC Secretariat.

https://www.eac.int/documents/category/key-documents

Owere, P. (2024, January 15). Tanzania blocks Kenya Airways flights in reciprocity dispute. The Citizen (Tanzania). https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/tanzania-blocks-kenya-airways-flights-in-reciprocity-dispute-4492578

Plus News Uganda. (2025, July 30). Kenya and Uganda sign eight MOUs to boost bilateral ties and economic growth. Plus News Uganda.

Reuters. (2025). Uganda secures $800 million from Islamic Development Bank for rail link to Kenya. Reuters.

Kitimo, A., & Wachira, B. (2021, December 13). Tanzania stalls Central Corridor modernisation.

The East African. The East African. (2025, July 30). Museveni, Y. K., & Ruto, W. Kenya and Uganda sign 8 bilateral deals during Museveni’s Nairobi visit. The East African.