1.0 Introduction

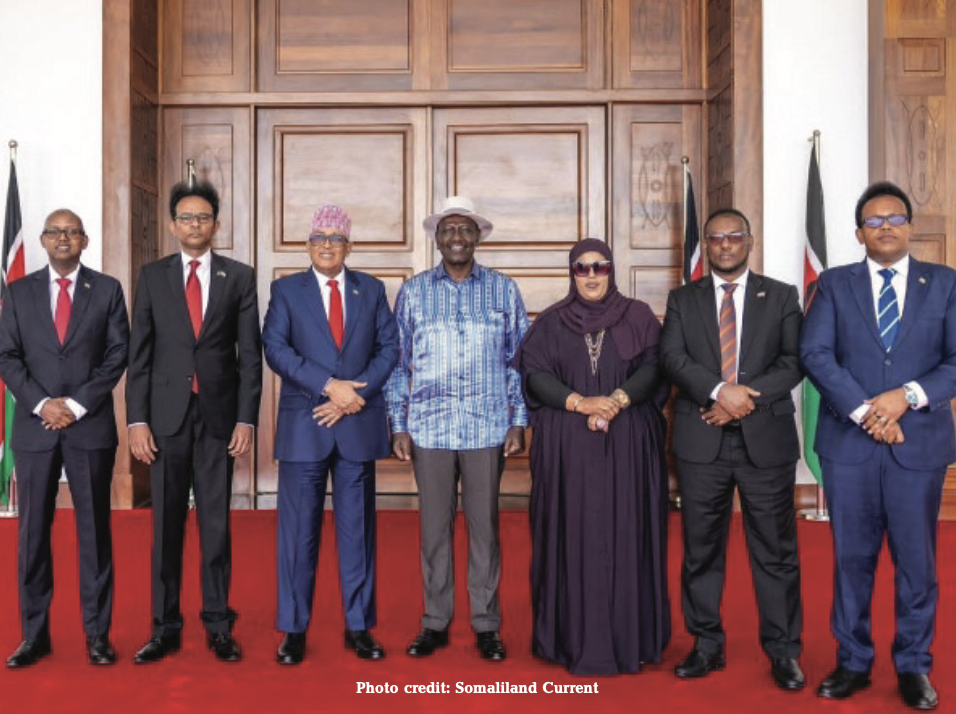

On 29 May 2025, the self-declared Republic of Somaliland inaugurated what it described as an “Embassy” in Nairobi, Kenya. This move occurred despite the territory not enjoying formal recognition as a sovereign state by any member of the United Nations or the African Union. The inauguration followed a high-level diplomatic engagement involving Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi and Kenya’s President William Ruto. Although Kenyan authorities later clarified that the mission is formally a Liaison or Representative Office, the symbolic use of the term “Embassy” triggered notable regional reactions, particularly from the Federal Government of Somalia, which maintains that Somaliland remains an integral part of its sovereign territory (ICG, 2025; Al Jazeera, 2025). This development mirrors similar diplomatic engagements in 2024, when Somaliland opened a representative office in Addis Ababa.

In both instances, host countries—Kenya and Ethiopia—adopted carefully calibrated language and positioning, allowing the missions to open without formally recognizing Somaliland’s sovereignty. These choices reflect nuanced diplomatic strategies that prioritize regional interests while observing established legal frameworks (Walls, 2023; ISS Africa, 2024). Although the Kenyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a Note Verbale affirming its support for Somalia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, the diplomatic implications of Somaliland’s outreach remain significant. These engagements reflect an evolving model of “symbolic diplomacy,” through which territories lacking formal recognition seek to establish international visibility and normalize their status incrementally (Bradbury & Healy, 2023). The Nairobi development also coincides with broader geopolitical shifts in the Horn of Africa, including Ethiopia’s 2024 Berbera port agreement with Somaliland and Kenya’s recent recognition of Kosovo—indicators of growing diplomatic fluidity in the region (Reuters, 2025). This commentary discusses the opening of Somaliland office in Kenya and its implications to future relations between Somalia and Kenya.

2.0 Key Issues

2.1 Kenya’s Diplomatic Balancing Act: Legal Norms and Strategic Interest

Since it declared independence in 1991, Somaliland has operated as a de facto autonomous entity, developing institutions, maintaining relative security, and conducting elections. Nonetheless, it continues to lack international recognition (Menkhaus, 2023). Kenya’s willingness to host Somaliland’s office—albeit within the confines of a non-recognition framework—signals a complex balancing of principles and pragmatism. Kenya remains a committed member of the African Union, which emphasizes the inviolability of existing borders. At the same time, Nairobi’s engagement with Somaliland reflects practical considerations, including access to the Berbera port, enhanced regional trade prospects, and opportunities for coordinated responses to transnational security threats such as Al-Shabaab (Odhiambo,2025; ISS Africa, 2024).

Kenya’s approach, often described as “constructive ambiguity,” enables a degree of functional cooperation without constituting formal diplomatic recognition. This strategy, while tactically useful, is not without diplomatic sensitivities. It requires continuous communication to prevent misinterpretation and maintain equilibrium in Kenya’s broader foreign policy posture (ICG, 2025).

2.2 Impacts on Kenya–Somalia Relations

The historical relationship between Kenya and Somalia has been shaped by mutual security concerns, migration dynamics, and economic ties. However, issues such as border disputes and maritime claims have at times strained bilateral trust. The inauguration of Somaliland’s office in Nairobi has introduced renewed tension. From Mogadishu’s perspective, such moves—regardless of stated intentions—may appear to confer legitimacy on Somaliland’s political aspirations (Al Jazeera, 2025).

This concern is both symbolic and strategic. Symbolically, Somaliland’s diplomatic footprint in Kenya may be viewed as undermining Somalia’s sovereignty. Strategically, it could embolden other federal member states or regional authorities to seek similar arrangements, thereby complicating Somalia’s ongoing state-building agenda (UNDP Somalia, 2024).

Despite the Kenyan government’s prompt diplomatic reassurances, historical precedent indicates that such issues can have lasting effects. Notably, in 2021, a previous visit by Somaliland’s leadership to Nairobi led Somalia to temporarily recall its ambassador, highlighting the deep sensitivities involved (ISS Africa, 2023).

2.3 Geopolitical Dimensions and Ethiopia’s Expanding Role

The Horn of Africa is witnessing evolving geopolitical dynamics, influenced by the strategic interests of regional and external actors. Ethiopia’s 2024 memorandum of understanding with Somaliland, which facilitates maritime access through the Berbera corridor, reflects Addis Ababa’s growing assertiveness in regional economic integration and security planning (African Development Bank, 2024; ICG, 2024). Concurrently, Kenya’s own infrastructure and logistics ambitions—exemplified by the LAPSSET Corridor and Lamu Port initiatives—require diversified partnerships. Engagement with Somaliland may therefore be viewed as part of a broader strategy to enhance regional connectivity and economic resilience (LAPSSET Authority, 2025). However, these alignments carry potential diplomatic implications. The Federal Government of Somalia has voiced strong opposition to the Ethiopia–Somaliland agreement and may perceive Kenya’s interactions with Somaliland as further challenging Somalia’s territorial status. In this context, Kenya needs to maintain strategic impartiality while advancing shared regional interests (AU Peace and Security Council, 2024).

2.4 Implications for Somalia’s Statebuilding and Stabilization Efforts

Somalia continues to navigate a complex political and security landscape marked by institutional fragility, persistent threats from non-state actors, and humanitarian pressures. Kenya has played a substantive role in Somalia’s stabilization process, including participation in the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) and support for refugee protection and cross-border development (UN Security Council, 2024; NRC, 2025). Somaliland’s distinct governance trajectory and relative stability present both opportunities and challenges. While there is a pragmatic case for regional cooperation with Somaliland on trade, health, and security, overt engagement risks perceptions of legitimizing secessionist claims. Kenya must therefore adopt a principled, inclusive, and carefully calibrated approach that supports Somalia’s unity while recognizing on-the-ground realities (Healy, 2023; Bradbury & Walls, 2024).

3.0 Conclusion

The establishment of Somaliland’s liaison office in Nairobi highlights the growing complexity of diplomacy in the Horn of Africa. As de facto governance arrangements increasingly intersect with traditional state structures, Kenya’s diplomatic posture will have significant implications for regional stability, integration, and influence. By articulating a coherent and principled framework—rooted in legal clarity, inclusive dialogue, and mutual interests—Kenya can position itself as a credible and constructive actor in regional peacebuilding and diplomacy.

4.0 Policy Recommendations

4.1 Clarify the Legal Status and Functions of Liaison Offices

Kenya should institutionalize a clear framework defining the roles, limits, and nomenclature of liaison or representative offices, particularly those affiliated with non-recognized entities. This will ensure transparency and reinforce 05MRPC Commentary Kenya’s commitment to the principles of international law and African Union norms (AU Legal Affairs Directorate, 2024).

4.2 Support Structured Dialogue Between Somalia and Somaliland

Kenya could serve as a neutral platform for constructive dialogue between Mogadishu and Hargeisa. While full recognition may not be on the agenda, cooperative engagement in areas such as trade, public health, and security can foster mutual understanding and reduce tensions (UNDP Somalia, 2024; Rift Valley Institute, 2025).

4.3 Enhance Regional Security Cooperation

Kenya should prioritize trilateral security coordination involving Somalia, Somaliland, and itself to address shared threats such as terrorism and illicit cross-border activities. Collaborative frameworks can help build trust while enhancing regional stability (ISS Africa, 2024; NRC, 2025).

4.4 Promote Inclusive Economic Integration

Kenya’s leadership in regional infrastructure initiatives provides an opportunity to foster economic interdependence across politically sensitive boundaries. By designing inclusive economic corridors and port linkages that benefit all stakeholders, Kenya can contribute to a shared vision of regional prosperity and peace (World Bank, 2025).

5.0 References

African Development Bank. (2024). Ethiopia Country Strategy Paper 2024–2028. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/ethiopia-country-strategy-paper

African Union (AU). (2024). Decisions and Declarations of the Assembly on Territorial Integrity. https://au.int/en/decisions-territorial-integrity

AU Legal Affairs Directorate. (2024). Guidelines on Diplomatic Representation and Recognition. https://au.int/en/legal-affairs-guidelines

AU Peace and Security Council. (2024). Briefing on the Horn of Africa Geopolitical Developments. https://au.int/en/psc-briefing-horn-africa

Al Jazeera. (2025, May 30). Somalia Reacts to Somaliland’s ‘Embassy’ Opening in Kenya. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/5/30/somalia-reacts-somaliland-embassykenya

Bradbury, M., & Healy, S. (2023). Recognising Somaliland: What Are the Options? Rift Valley Institute. https://riftvalley.net/publication/recognising-somaliland

Bradbury, M., & Walls, M. (2024). The Long Road to Recognition: Somaliland’s Foreign Policy. https://riftvalley.net/publication/long-road-recognition

Healy, S. (2023). Horn of Africa Diplomacy in Flux: De Facto States and Shifting Sovereignties. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/ horn-africa-diplomacy

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2024). Ethiopia’s Red Sea Gambit and Its Risks. https://www.crisisgroup.org/ethiopia-red-sea-gambit

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2025). Diplomacy and Symbolism: Somaliland in Nairobi and Addis. https://www.crisisgroup.org/somaliland-diplomacy-nairobi-addis

Institute for Security Studies (ISS Africa). (2023). Kenya–Somalia Relations: Past Lessons, Future Pathways. https://issafrica.org/publication/kenya-somalia-relations

Institute for Security Studies (ISS Africa). (2024). Somaliland and the Horn’s New Diplomatic Frontiers. https://issafrica.org/publication/somaliland-diplomatic-frontiers LAPSSET Authority. (2025). Strategic Infrastructure and the Northern Corridor Vision. https://lapsset.go.ke/strategic-infrastructure-visionMenkhaus, K. (2023). State Fragility and Alternative Governance in Somalia. https://examplejournal.org/doi/10.1234/afsj.2023.5678

Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). (2025). Kenya–Somalia Borderlands: Humanitarian and Security Perspectives. https://www.nrc.no/resources/kenya-somalia-borderlands Odhiambo, A. (2025). Strategic Dilemmas: Kenya’s Somaliland Policy in Context. Mashariki Policy Review. https://mashariki.org/strategy/kenya-somaliland-policy

Reuters. (2025, May 29). Somaliland Opens Nairobi Office as Kenya Recognizes Kosovo. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/kenya-somaliland-office-kosovo-2025-05-29

UNDP Somalia. (2024). Pathways to Peace: Inclusive Governance and Regional Dialogues. https://www.undp.org/publications/pathways-peace-somalia

UN Security Council. (2024). Report of the Secretary-General on ATMIS Operations. https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/report/atmis-2024

Walls, M. (2023). Somaliland’s Quest for International Legitimacy: Strategic Shifts and P D Realpolitik. https://www.afraf.oxfordjournals.org/content/122/487/561