1.0 Introduction

Eastern Africa has re-emerged as a strategic fulcrum in the twenty-first-century geopolitics, attracting converging interests from the Gulf states, China, and Western powers (Pinto, 2024). The region’s proximity to the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Western Indian Ocean positions it as a critical maritime and energy corridor, central to global trade, resource flows, and transnational security (Opondo, 2023). As the global order evolves toward multipolarity, Eastern Africa has become both a beneficiary and a stage for competing visions of influence and development (Kacungira, 2025). The Gulf states, particularly the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have expanded their economic and strategic presence in the region through targeted investments in ports, logistics, and agribusiness hubs, including Berbera, Lamu, and Port Sudan (Hassan, 2023; Khalid & Mwangi, 2024). Concurrently, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is reshaping infrastructure, rail corridors, industrial zones, and digital networks, reinforcing Beijing’s long-term influence by integrating Eastern Africa into Eurasian trade and technological systems (Zhou & Adeoye, 2023). Meanwhile, the United States and European partners have strategically recalibrated engagement, emphasizing maritime security, counterterrorism cooperation, and governance programming to balance rising Eastern influence (Matanga, 2024; White House, 2022). For countries such as Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Tanzania, these intersecting engagements provide economic opportunities but also pose complex policy challenges, including debt exposure, governance pressures, and security externalities (Kabiru, 2024). This commentary examines how Eastern African countries are navigating the Gulf–China–Western rivalry through multidirectional diplomacy and adaptive foreign policy, arguing that strategic balancing, anchored in regional cooperation and institutional resilience, offers the most viable pathway for safeguarding African agency amid intensifying great-power competition (Achieng, 2024).

2.0 Key Issues

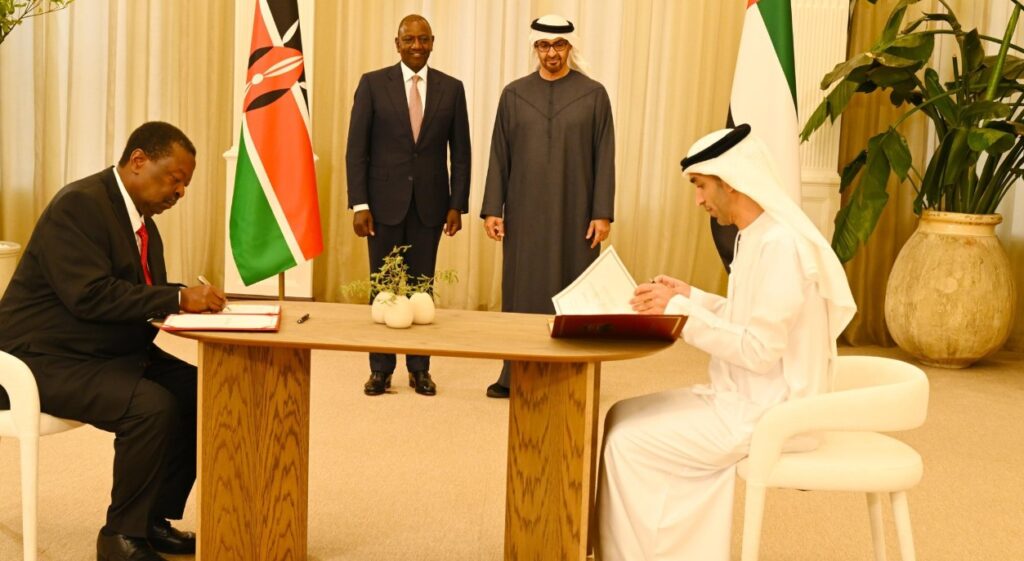

2.1 Gulf States’ Strategic Economic and Security Engagement in Eastern Africa

The Gulf states, particularly the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have deepened their economic and security footprint across Eastern Africa, leveraging investments in ports, logistics, and agribusiness to secure maritime influence, food supplies, and post-oil diversification (Khalid & Mwangi, 2024; Hassan, 2023). Strategic projects such as DP World’s Berbera Port and Saudi land acquisitions in Sudan and Ethiopia demonstrate a long-term approach to regional leverage (Omar, 2023). While these engagements provide critical capital and infrastructure, they also raise governance concerns, including opaque agreements, elite capture, and potential interference in domestic policymaking (Achieng, 2024). Balancing the economic benefits against sovereignty risks remains a key challenge for Eastern African states navigating this Gulf presence.

2.2 China’s Belt and Road Influence and Strategic Engagement

China continues to assert significant influence in Eastern Africa through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), financing railways, ports, industrial parks, and digital infrastructure that integrate the region into Eurasian trade networks (Zhou & Adeoye, 2023; Wu, 2024). While these projects enhance connectivity and economic development, they increase debt exposure and create structural dependencies, particularly in Kenya and Ethiopia (Mbaye, 2024). The Digital Silk Road further introduces complex risks regarding data sovereignty and surveillance technologies. Nevertheless, many Eastern African states view China as a reliable partner offering pragmatic alternatives to Western aid conditionalities. Striking a balance between leveraging Chinese resources for infrastructure growth and managing long-term financial and strategic risks remains essential for regional policymakers.

2.3 Western Strategic Re-engagement and Influence Counterbalance

The United States and European partners have intensified engagement in Eastern Africa to counterbalance rising Eastern influence, emphasizing maritime security, counterterrorism cooperation, democratic governance, and climate resilience (White House, 2022; Harris, 2023). Initiatives such as the U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa and the EU’s Global Gateway aim to provide transparent financing and sustainable infrastructure alternatives (Njeri, 2025). However, bureaucratic delays, conditionalities, and administrative constraints limit the speed and impact of Western engagement, prompting states to maintain diversified partnerships. Eastern African governments thus navigate between immediate developmental needs and strategic alignment, seeking to benefit from Western expertise while maintaining sovereignty and avoiding dependency, underscoring the necessity of pragmatic, multidirectional diplomacy.

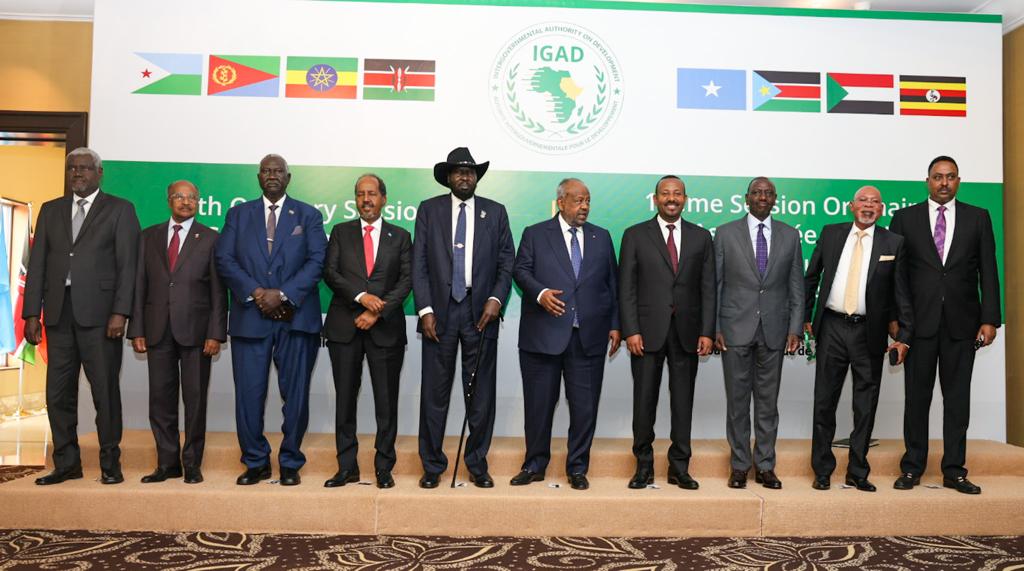

2.4 Eastern Africa’s Multi-Alignment Diplomacy and Strategic Autonomy

Eastern African states, including Kenya, Ethiopia, and Tanzania, increasingly pursue multi-alignment diplomacy to leverage the competing interests of Gulf, Chinese, and Western powers while safeguarding national sovereignty (Mekonnen & Ali, 2023; Omondi, 2025). This approach enhances flexibility, allowing states to maximize investment, technology transfer, and security cooperation. Yet, the strategy carries risks of fragmented policy and inconsistent engagement if not coordinated regionally. Strengthening institutions such as IGAD and the African Union can harmonize policy, improve transparency, and consolidate collective bargaining power (Elmi & Abdi, 2024). Regional cooperation, coupled with strong national frameworks, is essential for converting external competition into opportunities that support strategic autonomy and sustainable development.

3.0 Conclusion

Eastern Africa occupies a central position in the evolving global order, where Gulf, Chinese, and Western ambitions intersect. Multi-alignment diplomacy offers a pragmatic path for states to diversify partnerships, access capital and technology, and maintain strategic autonomy (Mekonnen & Ali, 2023). Success, however, depends on institutional resilience, transparent governance, and regional cooperation, ensuring that external engagement strengthens, rather than undermining, sovereignty and development priorities (Kacungira, 2025). By converting great-power rivalry into constructive collaboration through African-led frameworks, Eastern African states can secure long-term economic growth, regional stability, and geopolitical agency, positioning the region as a model for adaptive, sovereign, and resilient diplomacy (Achieng, 2024).

4.0 Policy Recommendations

4.1 Institutionalize Strategic Autonomy through Regional Coordination

Eastern African states should strengthen institutionalized strategic autonomy by enhancing regional coordination through IGAD and the African Union. By 2030, harmonized engagement frameworks can align foreign investment, debt management, and infrastructure projects with national development priorities, mitigating risks from debt dependency, policy incoherence, and security externalities. Establishing a regional Foreign Investment Code would ensure that Gulf, Chinese, and Western partnerships operate transparently and sustainably. Coordinated monitoring and dispute-resolution mechanisms can prevent elite capture, reduce geopolitical friction, and promote collective bargaining power. This approach positions the region to transform external interest into constructive, Africa-led development rather than reactive dependence.

4.2 Enhance Transparency and Accountability in Foreign Investment

Governments should adopt comprehensive disclosure frameworks for bilateral and multilateral infrastructure, security, and investment agreements. Publishing loan terms, feasibility studies, and procurement details will reduce corruption, elite capture, and structural vulnerabilities, while enhancing public trust. Regional institutions such as the African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions(AFROSAI) can develop auditing standards for cross-border projects, and strengthened parliamentary oversight to enforce compliance. Embedding transparency in strategic projects, including ports, railways, and industrial parks, ensures that partnerships with Gulf, Chinese, and Western actors deliver measurable development outcomes. By 2030, this proactive transparency will empower states to negotiate equitable terms, safeguard national interests, and maintain strategic flexibility in a competitive multipolar environment.

4.3 Build Local Capacity for Negotiation and Implementation

Eastern African governments must strengthen technical and institutional capacities to negotiate complex foreign agreements, ensuring long-term risk management and sovereignty protection. Specialized units within finance, trade, and foreign affairs ministries, supported by regional think tanks such as MRPC, can conduct scenario analysis, debt risk assessment, and project evaluation. Training policymakers in negotiation, contract management, and implementation oversight will reduce asymmetric dependencies on external powers. Applied consistently across infrastructure, security, and technology deals, this capacity-building approach equips states to anticipate challenges, safeguard African agency, and leverage partnerships for economic resilience. By 2030, robust local expertise will anchor multi-alignment diplomacy in informed decision-making rather than reactive compliance.

4.4 Diversify Partnerships while Prioritizing African Agency

Eastern African states should maintain African agency as the central principle guiding foreign engagement, leveraging diversified partnerships with Gulf, Chinese, and Western actors to maximize development benefits. Strategic diversification should prioritize transparent, interest-based cooperation aligned with national and regional priorities, rather than ideological alignment. Integrating these engagements with AU Agenda 2063 and IGAD frameworks ensures that infrastructure, technology, and finance projects advance collective economic security, regional integration, and sustainable development. By adopting this approach, Eastern Africa nations can mitigate external dependencies, strengthen bargaining leverage, and convert competitive pressures into opportunities for innovation, peace, and inclusive growth.

5.0 References

Achieng, L. (2024). Governance and foreign investment transparency in Eastern Africa: Navigating elite capture in strategic projects. African Policy Review, 12(2), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1186/apr.2024.055

Elmi, M., & Abdi, H. (2024). Gulf–China–US competition and African agency: The case of the Horn of Africa. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 18(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2024.2011056

Harris, J. (2023). The return of Western engagement in Africa: Security, climate, and connectivity. International Policy Quarterly, 9(3), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.5235/ipq.2023.077

Hassan, F. (2023). Ports, power, and politics: Gulf economic diplomacy in the Horn of Africa. Journal of African Geostrategy, 5(2), 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/jag.2023.009

Kabiru, D. (2024). Strategic autonomy and regionalism in Eastern Africa: Lessons for the African Union. Policy and Governance Review, 11(1), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/pgr.2024.088

Kacungira, N. (2025). Multipolar competition and African strategic balancing: A new era of pragmatic diplomacy. Africa Affairs Insight, 14(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/aai.2025.009

Khalid, R., & Mwangi, J. (2024). Ports of power: The UAE’s maritime strategy in the Red Sea corridor. Middle East and Africa Studies Review, 10(2), 112–130. https://doi.org/10.2307/measr.2024.112

Matanga, P. (2024). Western counterbalances to China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Eastern Africa. Strategic Studies Journal, 13(2), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1057/ssj.2024.065

Mbaye, K. (2024). Digital Silk Road and African sovereignty: Emerging challenges in cyberspace governance. African Technology Policy Journal, 7(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1109/atpj.2024.048

Mekonnen, L., & Ali, S. (2023). Non-alignment in practice: Eastern Africa’s multi-vector foreign policy. African Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, 9(4), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/ajdir.2023.033

Njeri, T. (2025). Recalibrating Western aid: Europe’s Global Gateway and Africa’s development sovereignty. Development and Cooperation Review, 8(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/dcr.2025.058

Omar, Y. (2023). Faith and finance: Saudi soft power in the Horn of Africa. Middle East–Africa Policy Perspectives, 6(2), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/meapp.2023.022

Omondi, C. (2025). Debt diplomacy and strategic dependence: Africa’s negotiating capacity in the multipolar era. African Economic Governance Review, 15(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/aegr.2025.081

Pinto, L. (2024). Geopolitical shifts and the new scramble for Eastern Africa. Global Policy Forum, 12(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/gpf.2024.019

White House. (2022). U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/08/us-strategy-toward-sub-saharan-africa

Wu, Y. (2024). Infrastructure and influence: Assessing China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Eastern Africa. Asian–African Economic Studies, 5(3), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/aaes.2024.097

Zhou, P., & Adeoye, M. (2023). China’s long game in Eastern Africa: Infrastructure, digital power, and diplomacy. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 41(3), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/jcas.2023.121