Introduction

Peace is a contrived reality that comes into being when various players agree that it should be contrived. The reasons for striving to make peace range from the hurt associated with negative conflicts, pressure from interested groups who act as mediators, and the possibility of a unifying ‘enemy’ emerging. Players can also destroy existing peace because it seemingly does not serve specific interests. This appears to have been the case in Sudan where leaders, once comrades, have turned on each other and plunged the country into conflict. The effort to restore peace in Sudan has seemingly hit hard rocks in all the three aspects that can be expected. The first aspect is that of the antagonistic internal forces agreeing to stop fighting because it makes sense and is in their common interest. The second aspect is that of the neighbors’, through the agency of IGAD as the regional body in which Sudan is a member, using their influence to mediate the feuding sides because it is in their individual and collective security interest to stabilize the region. The third aspect is that of relying on extra-continental forces that have power and resources to act in concert to pressure the quarrelling sides to patch up their differences. A convergence of the three aspects might bear fruits but it currently looks unlikely. This commentary reflects on the local, regional and extra- continental dynamics relevant to building peace in the Sudan.

Internal Aspect with Sudan

The possibility of internal groups agreeing to be peaceful faces many challenges that include Sudan’s territorial size, socio-culturally fragmentation, and competing religious and nationality identities. Its political boundaries are essentially products of the 19th Century European imperial competition for territories in Africa with Britain taking the lead which lumped together many peoples and tried to force them to be one in the service of the colonial state. Having acquired Egypt in the north, Britain grabbed British East Africa and set Ethiopia’s southern boundaries with Uganda and Kenya. It also secured Sudan’s borders with Italian claimed Libya in the northwest and Eritrea on the Red Sea. In the process, the three European powers made Ethiopia landlocked by grabbing the Somali coast and parts of the Red Sea. Similarly, British agreements with the French set Sudan’s borders with Chad and Central African Republic in the west. In the process, Britain kept France and Italy from Sudan in order, so its apologists argue, to protect its perceived strategic interests in the Nile River as a way of safeguarding the Nile, Egypt, the Suez Canal, and India.

Post-colonial Sudan was therefore a colonial construct in search of elusive nationhood because socio-cultural fragmentations and contradictions made national cohesion a distant ideal.

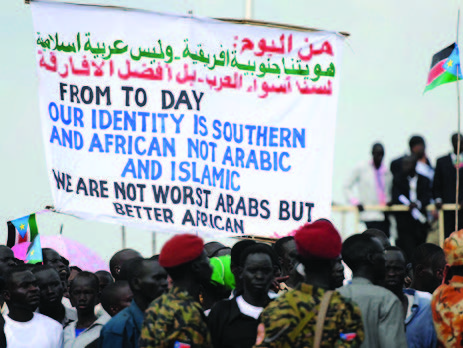

To start with, non-Arab sections had suffered multiple colonialism in which the people experienced Arab domination, under Anglo-Egyptian thumb, and answerable to England. Sudan’s official 1956 independence, therefore, was independence for the Arabs but not for the Africans.

This reality led to a prolonged civil war that had religious and ethnic divisions which visions of nationalism could not bridge. Subsequently, the term ‘nationalism’ became synonymous with rulers in Khartoum suppressing given identities which in turn generated resistance. The suppression of identities was mainly twofold. First, was Khartoum’s attempt at both forced Islamisation and Arabisation. Second, were the contradictions within each region mostly over ethnic affiliation and power play. These culminated in the independence of South Sudan in 2011 which reduced the territory of Sudan.

Since the phenomenon of suppression and resistance was not confined to the relations between the north and the south, national cohesion seemed to be increasingly distant. The distance was religious, mainly between Islam and Christianity, and also acquired regional characteristics. It was statewide and involved such other regions as Darfur, Kordofan, Gezira, and Abyei. They generated crises of cohesion as rivalries of political identities and leadership dominated interethnic relations. The number of ethnic groups within regions and the country, each with ambitious politicians seeking power, therefore, made creating sense of Sudanese nationalism difficult. Instead, attention turned to creating small political identities in rivalry with other emerging little political entities competing for national and international attention. The internal aspect of attaining peace in Sudan, therefore, has serious challenges.

Aspect of the Neighbors ‘and IGAD

The aspect of Sudan’s neighbors’ doing something positive appears promising but it ends up encountering geopolitical obstacles. These include having to contend with the interests of its geographical neighbors’ whose activities, internal or external, directly affect it. Sudan’s major neighbors’ are Egypt in the north and Ethiopia in the east and neither is in a position to bring peace to Sudan. From its time as co-ruler of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, mainly to ensure control of the Nile River flow, Egypt treats Sudan as a junior surrogate. Under the British rule, colonial officials in Egypt, Sudan, and Uganda ignored Ethiopia in signing the 1929 Nile River Treaty that gave Egypt rights to the Nile. In 1959, independent Egypt and Sudan signed another Nile Treaty and still ignored Ethiopia and other Nile riparian zones. Probably for that reason, Ethiopia repeatedly collides with Egypt and Sudan over the use of the waters of the Nile and both sides do not appear likely to agree because their priorities and perceptions of national interests and national security are diametrical to each other. Ethiopia decided to build the Grand Renaissance Dam despite Egyptian objections. Although Egypt is currently pre-occupied with the Israeli connected crisis in Gaza, it backs al-Burhan further complicating mediation efforts. Sudan and Ethiopia also tend to exchange periods of instability partly based on religious differences with Ethiopia claiming to be Christian while Sudan is mostly Islamic and its rulers claim to be Arabic. Egypt and Ethiopia are unlikely to help Sudan out of its condition of un-peace.

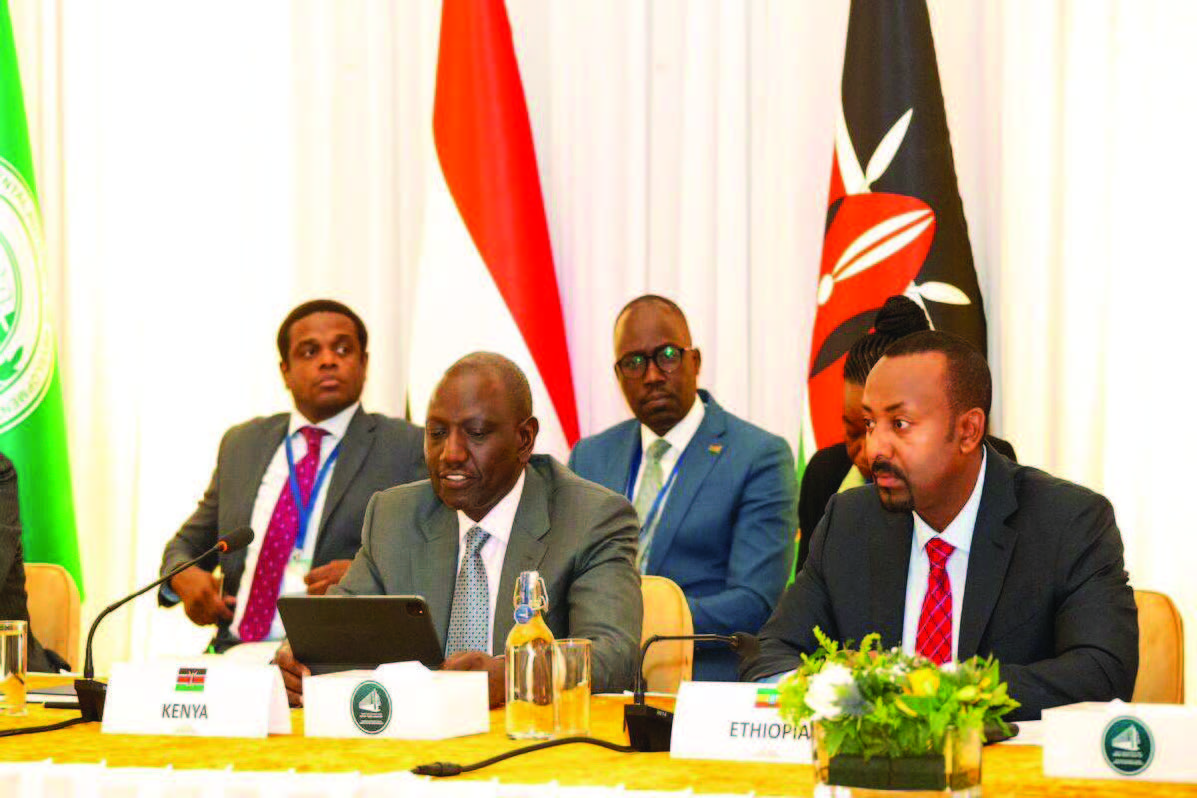

Attention turns to Kenya which likes playing Eastern Africa regional peace maker and at times peace keeper but it currently has a serious dispute with Sudan. It succeeded in helping to separate South Sudan from Sudan partly by soothing Omar al-Bashir into accepting the reality of separation. Kenya does not seem to command the same respect as it used to have when it helped to birth South Sudan. With the chaos in Sudan, South Sudan has become a recipient of refugees from Sudan and intensifies instability which affects Kenya’s sense of security. Kenya is thus in a fix and has lost its previous role as a regional peace maker and IGAD does not have capacity to force feuding parties into agreements. Neither Kenya, nor IGAD, knows how to handle feuding Sudanese generals, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan who leads the Sudanese Armed Forces ((SAF) and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti) and his Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Previously, the two generals were allies and al-Bashir’s Janjaweed operators in Darfur. They also worked together in ousting Al-Bashir but their alliance did not last as mutual suspicion about power grab, each commanding a strong militia, turned them into power rivals. When IGAD designated Kenyan President William Ruto as chair of a mediation team, the exercise was doomed because Burhan objected by claiming that Ruto was overly friendly to Hemedti and could not, therefore, be a fair arbiter to the Sudan internal dispute. Subsequently the IGAD mediation mission became a cropper because of the intense mistrust within Sudan and within IGAD as a regional organization. IGAD and the neighbors’ are thus incapable of delivering peace to Sudan

Part of the reason that IGAD has no capacity, besides mutual distrust and suspicions, is that IGAD, as an organization, is excessively dependent on extra-continental forces for finances and logistical support, especially the European Union, in whatever it decides to do. The problem is not just an IGAD one, it also afflicts individual member countries who continue to look up to extra-continental powers to do what needs doing. The implication is that IGAD will not bring peace in Sudan for it has neither the will nor the capacity. This has the effect of transferring the responsibility for bringing peace in Sudan to many competing extra-continental interests, each with its own agenda.

Extra-Continental Involvement

IGAD’s incapacity to deliver peace in the region raises the question of who exactly runs Sudan and its resources. External forces appear to be the ones with that capacity but they are split and seemingly not interested in peace in Sudan despite their repeated calls for restoration of peace and offers to host talks. Both al-Burhan and Hemedti have wealthy and influential backers, including United States, Russia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Turkey. The main concern for the United States is to check both Russian and Chinese influence in Sudan and the Horn of Africa region. It thought it could achieve that by pressuring Burhan and Hemedti to go civilian only to be forced to evacuate its officials to escape the violence. Its ability to press either side to peace is thus limited.

Other players have geo-strategic interests in the Red Sea and compete more for regional influence than trying to end the Sudan conflict. Saudi Arabia wants to control most of the Red Sea and seemingly had leverage on both camps. Previously, under al-Bashir, both al-Burhan and Hemedti had supplied Sudanese fighters for Saudi War in Yemen. This possible leverage enabled it to get Burhan and Hemedti to travel to Jeddah for mediation, although the talks did not bear fruits. Burhan has close links with Egypt and Turkey where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has desire to revive the Ottoman Empire and spread Turkish cultural influence in Africa. Although he offers to host peace talks, he appears to lean on and has received Burhan in Ankara, but not Hemedti and thus is not serious as mediator. While Burhan has close links with Egypt and Turkey, Hemedti has linkages with Russia whose interest is in acquiring a port on the Red Sea as well as getting a large supply of Sudanese gold. Russia’s Wagner group helps Hemedti to humiliate al-Burhan in the on-going fighting. Hemedti also works closely with the United Arab Emirates, which funds his activities, and seemingly is a rival to Saudi regional agenda.

The likelihood of the extra-continental forces promoting peace in Sudan is therefore not high because of competing and entrenched interests. Whether the reason for their inability is geopolitical rivalry, desire to deny each other opportunities to do well, access to Sudanese resources, and support for individual ‘generals’, it is unlikely they will foster peace in Sudan. Instability and chaos enables them to thrive in pushing specific agenda which coincides with the individual power interests of the two fighting generals who used to be Janjaweed colleagues. The prospects for peace in Sudan, therefore, do not look promising.

Conclusion

Peace is a contrived reality that calls for the parties involved to be willing to design that peace despite the odds. That willingness appears to be absent when it comes to the Sudan conflict partly because of conflicting dynamics. Restoring peace in Sudan, examined from the three possible aspects or angles, will thus be difficult. Although it makes sense to imagine antagonistic internal forces agreeing to stop fighting for their common interest, the imagination is also not realistic. The people of Sudan have yet to accept that they are nationals of Sudan rather than quarrelling ethnic and religious regional entities each trying to assert its identity. The second aspect of expecting IGAD and the neighbours to help is a good dream of an ideal that has many handicaps. These include personal and country rivalries, mutual suspicions, unwillingness or inability to pay, and excessive dependence on extra-continental interests to fund IGAD or individual expenses. In the third aspect, relying on extra-continental forces is itself unreliable because of the competing geopolitical interests that work at cross purposes with each other and to the detriment of peace in Sudan. While a convergence of the three angles of promoting the peace agenda in Sudan might have a chance, actualizing it would be a tall order.

Bibliography

- Saadia Touval, “Treaties, Borders, and the Partition of Africa,” The Journal of African History, Volume 7, Issue 2, July 1966, pp. 279-293

- Jeffrey Herbst, “The Creation and Maintenance of National Boundaries in Africa,” International Organization, 43, No. 4, 1989, pp. 673-692

- W.F.S. Miles, Scars of Partition: Postcolonial legacies in French and British borderlands (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2014

- Wafula Okumu, “Resources and border disputes in East Africa,” Journal of Eastern African Studies, Volume 4, No. 2, July 2010, pp. 279-297

- Tasew Gashaw, “Colonial Borders in Africa: Improper Design and its impact on African Borderland Communities,” Africa Up Close: A blog of the Africa Program (Washington DC: Wilson Center Africa Program, November 17, 2017)

- Jason Burke, “ A war of our age: how the battle of Sudan is being fueled by forces far beyond its borders,” The Guardian, April 30, 2023

- Ishaan Tharoor, “Behind chaos in Sudan is a broader global power struggle,” The Washington Post, April 18, 2023

- Ashok Swain, “Ethiopia, the Sudan, and Egypt: The Nile River Dispute,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, Volume 35, No. 4, 1997, pp. 675-694

- Andrew Carlson, “Who Owns the Nile: Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia’s History- Changing Dam,” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective(Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University, March 2013)

- Salam Abdulgadir Abdulrahman, “Agreements that favour Egypt’s rights to Nile Waters are anachronism,” The Conversation, November 4, 2018

- Marina Ottaway, “Egypt and Ethiopia: The Curse of the Nile,” Middle East Program Viewpoints (Washington DC: Wilson Center, July 7, 2020)

- Alex de Waal, “Sudan Crisis: From Ruto to Sisi, leaders vie to drive peace process,” BBC NEWS, 13 July 2023

- Matthew Chandler de Waal, “The Future of IGAD amidst Turmoil in the Horn,” African Arguments, March 26, 2024

- Talal Mohammad, “How Sudan Became a Saudi-UAE Proxy War,” Foreign Policy (FP), July 12, 2023

- Declan Walsh, Christoph Koetti and Eric Schmitt, “Talking Peace in Sudan, the UAE Secretly Fuels the Fight,” The New York Times, September 29, 2023

- Sean Mathews, “Sudan: Conflict tests limits of Gulf powers’ new diplomacy,” Middle East Eye, 28 April, 2023

- Andrew Harding, “Sudan fighting: Why it matters to countries worldwide,” BBC News, April 20, 2023

- Christopher Tounsel, “Sudan’s plunge into chaos has geopolitical implications near and far-including for US strategic goals,” The Conversation, April 28, 2023

- Declan Walsh and Abdi Latiff Dahir, “War in Sudan: Who is Battling for Power , and Why It hasn’t Stopped,” The New York Times, Dec. 19, 2023

- Jonas Horner and Ahmed Soliman, “Coordinating International Responses to Ethiopia-Sudan tensions,” Chatham House Research Paper, 12 April, 2023

- Ezgin Akin, “Turkey’s Edorgan hosts Sudan’s Burhan as conflict in Khartoum drags on,” Al-Monitor, September 13, 2023

- Jihad Mashamoun, “Turkey and Sudan: An enduring relationship?” Middle East Institute, July 20, 2022

- Medya Zirvesi, “Erdogan’s neo-ottoman ambitions and offensive policy in Africa,” Middle East Research Center, MENA, 30 January, 2023

- Macharia Munene, “Geopolitical Dynamics in the Horn of Africa Region,” The Horn Bulletin, Volume V, Issue I, January-February 2022, pp. 1-11

- Macharia Munene, “Sudan Conflict: Why Kenya will need a smart ‘grand strategy’,” The Standard, April 24, 2023

- Macharia Munene, “China interest in Sudan could shift power alliances in resolving crisis,” The Sunday Standard, April 30, 2023

- Macharia Munene, “Conflict and Post-Colonial Identities in the East/Horn of Africa,” in K. Omeje, editor, The Crises of Postcoloniality in Africa (Dakar: CODESRIA BOOKS, 2015), pp. 123-142.

Macharia Munene is Professor of History and International Relations at USIU- Africa. The views expressed herein are his own.