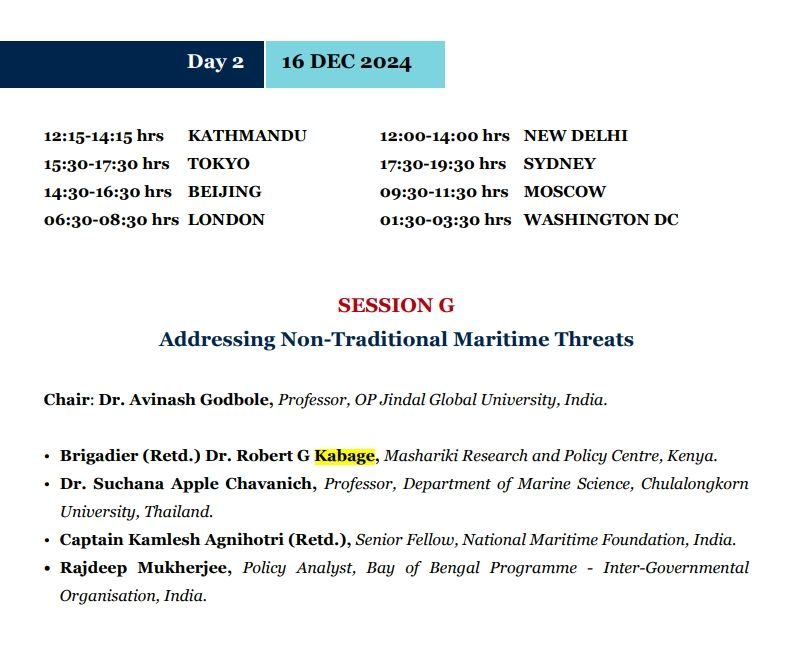

NIICE FORUM 16TH Dec 2024 on ‘Addressing Non-Traditional Maritime Threats’

Presented by Brig (Rtd) Dr R G Kabage, PhD, EBS, CEO, Mashariki Research and Policy Centre, Kenya

Background and Context

I centre my discussion on moving beyond the traditional security understanding that is state-centric and shift towards human security. The use of the terminology ‘non-traditional threats’ remains contested but nevertheless we shall use it in the presentation today. It has been contested because it is a Post-Cold War conceptualization that perceived that nation-states would not go to war with each other. This was the assumption in the post-Cold War era that states would now cooperate for good order in the sea, yet in the present, we see ever-changing global competition on the sea.

Non-traditional threats are contextualized in the literature to refer to interventions not directly related to naval warfare. This discussion fits within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14. This goal is about the sustainable use of oceans, seas, and marine resources. Conserving and sustainably using the oceans, seas, and marine resources. Oceans and seas are essential to human existence and life on Earth. They offer natural resources including food, medicines, biofuels, and other products. Moreover, oceans and seas are the planet’s greatest carbon sink.

This then allows us to reflect on issue areas such as environmental security and related food security threats in the context of non-traditional threats to maritime security. In the non-traditional maritime threats, we can talk about such issues as climate change, drug smuggling, piracy, sea robbery, terrorism, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUUF). These issues are often interlinked and cut across national and physical boundaries. These threats can be linked to state weaknesses, but also insufficient regional and international cooperation.

Focus on non-traditional maritime threats

In this presentation, I shall focus on four issues within the Western Indian Ocean region and later offer some suggestions on how to address these threats.

- Climate change

- Unregulated, unreported, and illegal fishing

- Maritime terrorism

- Ocean acidification

Climate Change and rise in sea levels

Rise in sea levels, linked to climate change, is a major environmental concern for the planet and one issue that is evident as a non-traditional threat. Rising sea levels are impacting coastal states on several scales; they are leading to ‘climate refugees’ due to the associated displacement. In addition, they are leading to flooding, salinity intrusion, and food insecurity. The Maldives Island is one of the developing nations facing this threat even as climate adaptation and mitigation interventions are put in place.

Unregulated, unreported, and illegal fishing

Littoral nations and coastal communities around the Indian Ocean are dependent on fishery for their livelihoods. IUU is referred to in the literature as ‘unsustainable practices that lead to the depletion of fish stocks’. The end result is that they are detrimental to the marine ecosystem. These activities are largely enabled by weak governance mechanisms where states are unable to police their marine resources. This then allows actors such as organized criminal groups to engage in these illegal activities. In the end, the potential of the blue economy, which is critical for socio-economic development, is impacted negatively by these illegalities.

Ocean acidification

Ocean acidification, which is linked further to global warming, is further impacting human security. The immediate implication is the negative impact it has on coral reefs. Coral reefs are a key building block towards coral fisheries. In addition, they are an important cog in food security for coastal populations, in addition to sustaining exotic tourist destinations. Addressing the impacts of climate change is therefore critical in this regard as a way to secure livelihoods while sustaining the earth’s resources.

Marine Terrorism

Maritime terrorism also has no internationally agreed definition (Moreels, 2016). A joint communication from the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the Council defines maritime terrorism as “any violent act with a political purpose against ships, cargo and passengers, ports and port facilities, and critical maritime infrastructure”. In the Indian Ocean region, there have been cases of these acts of sabotage by organized criminal groups, such as on the Somali coastline, and which disrupt maritime trade. The Houthis’ attack on ships in the Gulf of Aden late last year and parts of 2024 further demonstrate these challenges.

Addressing non-traditional security threats: Suggested counter interventions

- Cooperation of littoral states at regional and continental levels in areas of maritime security is important, such as in addressing issues like illegal and unregulated fishing. The Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC) agreed on in 2009 and ratified by up to 20 states is a maritime security agreement that aims to counter threats to the region, including piracy, armed robbery, human trafficking, and illegal fishing.

- Enhancing multilateralism, such as leveraging the opportunities for cooperation around such programs as the Indian Ocean Rim Association. This allows cooperation on matters of marine safety and security, as well as disaster risk management.

- Adherence by littoral states to mechanisms such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries of the United Nations (1995). This Code, which is voluntary, provides standards for marine resource conservation and management. The Code takes into account the economic, cultural, and environmental significance of these resources.

- Governments at bilateral and multilateral levels should initiate policy interventions for climate change adaptation and mitigation, including finding cooperative mechanisms.

- Adopting community-based institutional management of marine resources is a suggested policy intervention. It has been applied in contexts such as Kenya and Madagascar. These have been particularly applied in the context of coral reef management. Community-based approaches help to bring a wide range of stakeholders, which can be deemed as bringing multiple stakeholders to the conservation table. In this way, they also bring local knowledge and experiences to the table.