America First policies have begun to ripple across East Africa, and Kenya finds itself at the epicenter of this shifting tide. The dissolution of USAID’s assistance, which once formed the backbone of Kenya’s health and development programs, has triggered a fiscal reckoning with far-reaching consequences. With over 252 billion shillings in annual aid frozen and further cuts anticipated from European partners, Kenya faces a stark dilemma. In the wake of declining external assistance from traditional donors, will Kenya’s policy response hinge on debt accumulation? What will happen to critical sectors including health, agriculture, and social protection, which have historically depended on foreign funding? This commentary aims to analyze the fiscal repercussions of ongoing aid cuts, assess Kenya’s current policy responses, and evaluate whether further debt accumulation is becoming an inevitable course of action.

Key Issues

- The Scale of Aid Cuts and Immediate Economic Consequences

The reduction in foreign aid is not a gradual phasing out but a seismic policy shift. The United States, under the renewed America First orientation, implemented a 90-day suspension of foreign aid, a move quickly mirrored by Germany and the United Kingdom. The freeze has affected more than 34,000 jobs, predominantly in donor-funded NGOs and joint government programs, and has resulted in the halting of several critical projects in health, agriculture, and internal security.

USAID alone contributed more than 108 billion shillings annually to Kenya’s economy.[1]Of this, over 24.9 billion shillings supported health sector programs focused on HIV and AIDS treatment, maternal health, and tuberculosis response. The anticipated withdrawal of European Union support—Kenya’s second-largest donor bloc—places additional strain on efforts to meet Sustainable Development Goals related to poverty, public health, and inclusive growth.

These aid cuts are already causing tangible disruption across sectors. In health, over 6.4 million Kenyans risk losing access to essential HIV treatment and immunization services, heightening the danger of preventable disease outbreaks. The National Treasury has responded by slashing 68 billion shillings from the broader health budget, a decision that, while fiscally defensive, jeopardizes long-term public health gains.[2] Meanwhile, job losses across the NGO sector have led to a decline in household incomes, weakening consumer demand and reducing government tax revenues. Compounding this is the reduction in foreign currency inflows, which poses a threat to Kenya’s already volatile exchange rate. Although diaspora remittances estimated at $4.94 billion in 2024 have cushioned the immediate impact, this buffer remains insufficient to stabilize reserves in the medium term.[3]

- Kenya’s Rising Debt Burden and Fiscal Fragility

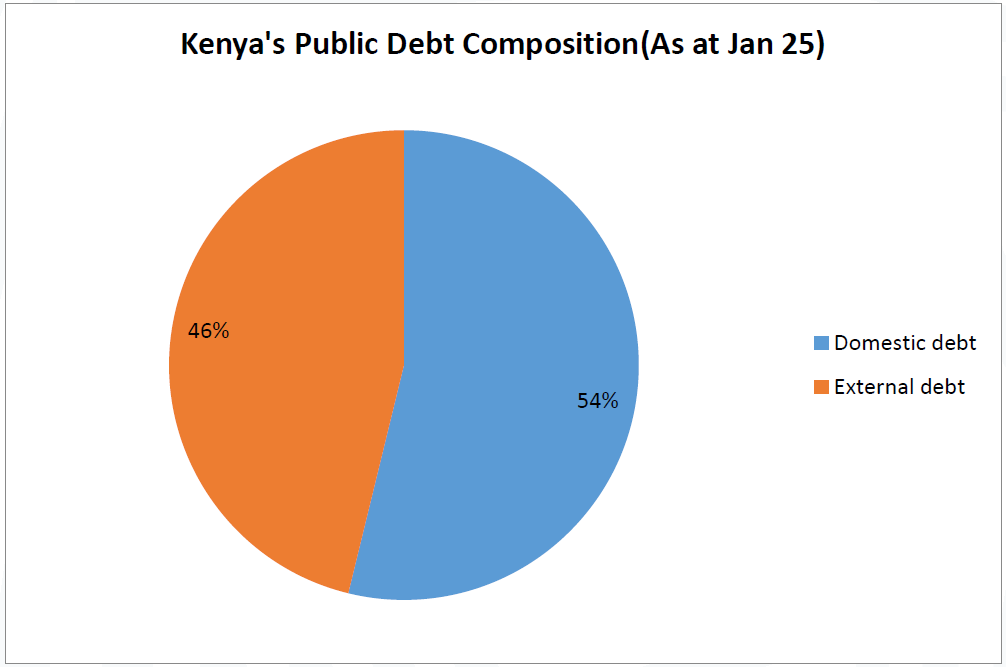

As foreign assistance dwindles, Kenya’s mounting public debt casts a long shadow over its financial resilience. By January 2025, total public debt had reached 11.02 trillion shillings, with 5.93 trillion sourced domestically and 5.09 trillion externally.[4]Alarmingly, debt servicing now consumes more than 60 percent of annual government revenue, squeezing out critical investments in education, infrastructure, and social protection.[5]

Source: The National Treasury

The country’s exposure to external debt has heightened its vulnerability to currency depreciation. Since 2024, Kenya has lost an estimated 1 trillion shillings purely due to exchange rate fluctuations, underscoring the risks of borrowing in foreign denominations.[6] At the same time, increased reliance on domestic borrowing, now accounting for 75 percent of new debt as per the 2025 Medium Term Debt Strategy, is creating a crowding-out effect. Private sector access to credit is diminishing as the government borrows more from local markets, pushing up interest rates and discouraging business expansion.

Legal constraints have been breached as well. Kenya’s debt-to-GDP ratio now stands at 63.7 percent, well above the statutory ceiling of 55 percent.[7]This breach has prompted calls for immediate austerity from the Controller of Budget and raised alarms among multilateral lenders. The International Monetary Fund’s decision to withdraw from its final loan review in early 2025 signaled deteriorating confidence in Kenya’s fiscal discipline and the sustainability of its economic policies.

- The Policy Response: Approaches and Implications for Economic Stability

In response to this fiscal crunch, the Kenyan government has adopted a tripartite policy approach consisting of fiscal consolidation, debt management reform, and alternative financing exploration. While these steps aim to stabilize the economy, they also raise questions about long-term effectiveness and the burden placed on different segments of society.

The first leg of the strategy involves reducing public spending and increasing revenue collection. The National Treasury has reallocated 24.9 billion shillings from development projects to support the health sector and cut non-essential government expenditure. On the revenue side, the government is enhancing digital tax systems, raising taxes on luxury goods, and introducing new levies targeting high-earning digital platforms. These efforts may help ease short-term pressure but also carry potential downsides. Increased taxation could hurt small and medium enterprises already struggling with high costs, while cutting development spending risks slowing down the very investments needed for future growth.

The second leg focuses on managing public debt more sustainably. The 2025 Medium Term Debt Strategy outlines a shift toward concessional loans and longer repayment periods to reduce the risk of refinancing challenges. The government is targeting a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio to 57.8 percent by 2028. Achieving this will require more than better borrowing terms—it will depend on sealing fiscal leakages, strengthening transparency, and improving how public funds are used. Without meaningful reforms, debt sustainability will remain out of reach.

Closely related is the concern around replacing foreign aid with additional borrowing. Kenya faces debt service obligations of 2.47 trillion shillings by 2027.[8] While more borrowing may provide short-term relief, it carries serious risks. Heavy reliance on loans, especially those that are non-concessional or lack transparency such as some Chinese financing agreements raises issues of long-term dependency and control over strategic national assets. Managing these relationships must be guided by national priorities, not short-term fixes.

The third leg of the response involves exploring alternative financing options. The government is seeking to grow the diaspora bond market, attract private investment through public-private partnerships, and issue green bonds linked to environmental goals. These initiatives could unlock new sources of funding, but they require strong institutions, clear regulation, and stable political conditions to be effective.

At the same time, some of the measures being implemented to manage the situation are beginning to affect ordinary citizens. Subsidies on fuel and food are being reduced, and proposals to raise value-added tax are under discussion. These steps are likely to hit low-income households the hardest, widen inequality, and strain the relationship between the state and the public. With unemployment and living costs already high, public unrest especially in urban areas, is becoming increasingly likely.

Conclusion

Kenya’s deepening fiscal crisis compounded by foreign aid cuts and unsustainable debt obligations, has exposed the structural fragility of its development model. Short-term fixes such as reallocating budgets and increasing domestic borrowing can only go so far. Without a paradigm shift in how the country mobilizes and manages its resources, Kenya must seize this moment not with patchwork fixes, but with bold, forward-looking strategies to build resilience, equity, and inclusive growth.

Policy Recommendations

Kenya cannot borrow its way out of this crisis. What is needed is a decisive shift from stopgap measures to structural transformation.

First, the country must diversify its sources of development financing. Scaling up public-private partnerships in infrastructure, healthcare, and education can unlock both domestic and foreign capital. The issuance of green and social bonds should be expanded to attract Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG)-aligned investors.

Second, governance and accountability must be strengthened. A comprehensive audit of existing debt obligations is necessary to identify and eliminate wasteful expenditure. Underperforming state-owned enterprises must be either restructured or privatized. Transparency and public participation in fiscal planning will be essential to restoring trust and improving resource allocation.

Third, Kenya should leverage diplomatic channels to renegotiate debt terms with both multilateral and bilateral partners. Efforts must be made to lobby for debt relief packages linked to SDG progress, not conditional austerity. Engagement with Eastern lenders such as China must be conducted on equal and transparent terms, avoiding collateralized loan traps and opaque contracts.

Finally, productivity-enhancing investments must take precedence. Rather than cutting spending indiscriminately, the government should prioritize investments in agriculture, digital infrastructure, and manufacturing. These sectors have the potential to generate employment, broaden the tax base, and reduce reliance on both aid and debt.

References

- Kenya HIV patients live in fear as US aid freeze strands drugs in warehouses. March 11, 2025.

- National Treasury of Kenya. 2025 Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy (MTDS). January 2025.

- Kenyan News Agency. Kenya unveils 2025 Medium-Term Debt Strategy to strengthen public debt management. March 26, 2025.

- Amnesty Kenya. What challenges does Kenya face post-aid cuts?. March 10, 2025.

- Trading Economics. Kenya Government Debt to GDP. March 2025.

- Mwananchi Version of MTDS Report. Kenya’s 2025 Medium-Term Debt Management Strategy. March 2025.

- Kenyan News Agency. Retrenchments loom as USAID cuts health funding in Kenya. February 12, 2025.

- CEIC Data. Kenya Government Debt: % of GDP, 2009–2025. September 1, 2024. Strategy