1.0 Introduction

As the 2025 Burundi elections approach, the country’s political landscape remains fraught with challenges that threaten the core principles of governance and democracy. Ongoing political repression coupled with media suppression configure a precarious environment that would undermine the credibility and transparency of any electoral process.

Burundi is yet to politically stabilize following the civil war that raged from 1993 to 2005. The disputed 2015 constitution particularly worsened the situation following the unconstitutional extension of President Pierre Nkurunziza’s presidential term.[1] Similarly, the country’s ruling party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), has increasingly consolidated its grip on power, instilling a climate of fear and intimidation.[2]

This development not only casts a shadow over the legitimacy of the upcoming 2025 elections but also severely hampers the National Council for Freedom (CNL)’s capacity to engage effectively in the political arena.[3] The suspension of the CNL, which culminated in the ousting of its leader, Agathon Rwasa, while he was abroad in Tanzania, has sparked widespread concern. Prominent African opposition figures have criticized this move as a serious threat to Burundi’s democratic fabric. In a functional democracy, political parties must operate in an environment that supports open campaigning and the free promotion of their platforms. This essential component of political pluralism ensures that voters can make informed choices and that power transitions reflect the true will of the populace. According to the Democracy Index 2024, Burundi’s ranking in terms of democratic freedoms underscores the challenges it faces in establishing such a conducive political climate.[4] These constraints highlight the urgent need for reforms to safeguard democratic participation and political inclusivity.

In light of the discussion above, this commentary will analyze Burundi’s current democratic situation and explore policy recommendations in preparation for the country’s 2025 elections.

2.0 Key Issues

2.1 Political and Media Repression

Governance in Burundi is seriously hampered by high levels of corruption, an absence of transparency, and an eroding rule of law. The executive branch holds disproportionate power,[5] greatly weakening the balancing roles that the legislative and judicial branches of government should play. The result is that accountability for human rights abuses remains a mirage, and the manipulation of independent electoral institutions raises heightened fears of electoral manipulation and fraud.[6]

Citizens, burdened by economic challenges and limited access to essential services, face increasing frustration under a government focused on maintaining its hold on power. Such prevailing discontent poses the risk of heightened tensions and potential unrest, particularly when electoral processes are perceived as lacking transparency or legitimacy.

2.2 Human Rights Violations

The human rights situation in Burundi is alarming with various international organizations documenting a systemic pattern of extra-judicial killings, torture, and enforced disappearances against political opponents and dissenters.[7] Suppression by the government around freedoms of expression and assembly further throttles civil society, prohibiting it from playing a meaningful role in ensuring accountability and democratic governance. As the date of elections draws closer, the potential danger of increased violence and human rights abuses further heightens, especially if opposition campaigns are effective. The past response of the government to dissent gives great cause for concern over its acceptance of free and fair elections.

The political situation in Burundi carries significant implications for regional stability in East Africa. The potential for spillover violence and instability affecting neighboring countries cannot be overlooked. Historical cases have demonstrated that political unrest in Burundi has often triggered refugee flows and cross-border tensions, impacting the region’s overall security. Effective intervention, particularly from regional bodies such as the African Union (AU) and the East African Community (EAC), could be pivotal in shaping Burundi’s political trajectory and mitigating crises. Mechanisms such as early warning systems, dispatching the AU’s Panel of the Wise, and concerted diplomatic engagement are essential to prevent escalation and foster a climate of accountability. In the past, insufficient responses have allowed the Burundian government to act with impunity, perpetuating cycles of violence and repression. Strengthened regional oversight could play a crucial role in breaking this cycle and promoting stability.

3.0 Recommendations

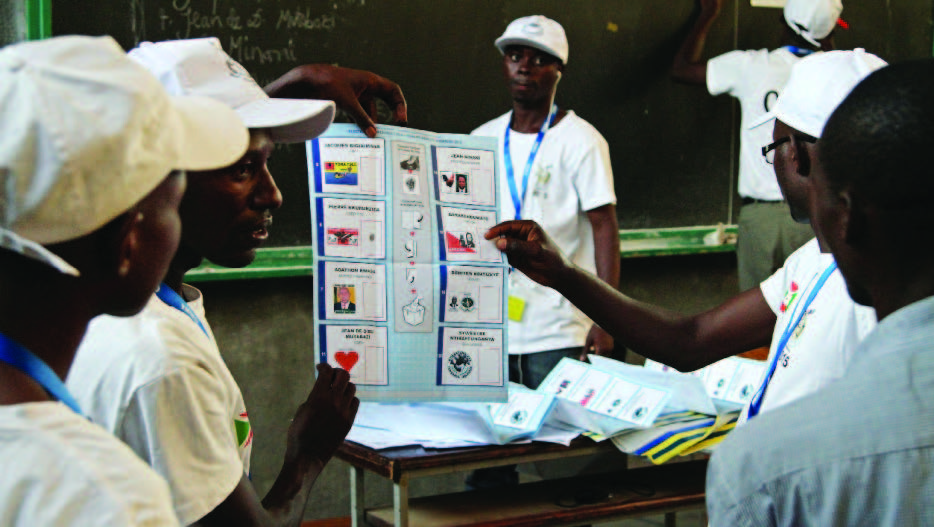

In light of the above analysis, a comprehensive policy approach is essential to create a more democratic and stable environment for the 2025 elections. Key to this is the establishment of an autonomous election commission, whose capacity should be strengthened through support from international partners and regional bodies like the EAC. This commission would be tasked with overseeing the electoral process to ensure its transparency and fairness, handling all aspects from voter registration and candidate vetting to voting supervision, vote counting, and the announcement of results. For this framework to succeed, the commission must be empowered to operate independently, free from government interference, to rebuild public trust in the electoral system—a trust that was notably eroded during the 2020 election in Burundi.[8]

Equally important is the role of electoral observation missions. Previous reports by the AU and EAC have underscored the value of these missions in promoting transparency and accountability. Their presence helps to deter electoral malpractice and provides credible assessments that can guide post-election reforms. Incorporating seasoned electoral observers who can make real-time recommendations and report findings publicly would enhance the legitimacy of the electoral process. The combination of a robust, autonomous electoral commission and the deployment of reputable observation missions would be pivotal in shaping a fair and peaceful election in 2025.

Advocating for a national dialogue that includes all political actors—opposition parties, civil society organizations, and marginalized communities—will be essential. Such dialogue can serve as a critical platform for addressing historical grievances, fostering a more tolerant political atmosphere, and building consensus on electoral reforms. The Arusha Accord of August 2000, which played an instrumental role in ending Burundi’s civil war and setting the stage for peace, is a testament to the importance of inclusive dialogue. This historic agreement highlighted the significance of addressing identity politics, particularly the Hutu/Tutsi dynamics, and underscored the necessity of balancing representation to promote stability.

By drawing lessons from the Arusha Accord, current efforts can be aimed at creating a framework for constructive debate that allows different voices to shape the political landscape. Such an approach not only nurtures reconciliation and cooperation but also reduces the risk of election-related violence. Additionally, it is essential to recognize the influence of regional neighbors, whose roles can either contribute to or destabilize peace efforts, making strong, inclusive dialogue even more critical for sustainable peace and democratic progress.

Equally important is the establishment of an independent international mechanism to monitor human rights conditions, particularly during the electoral period. Such a body should be mandated to investigate human rights abuses, document violations, and provide actionable recommendations for both the Burundian government and the international community. Ideally, this mechanism could be led by regional or international entities such as the African Union (AU), the East African Community (EAC), or the United Nations (UN). Its success would hinge on collaboration with the host state, which would need to permit its operation and ensure cooperation with domestic authorities.

The involvement of a recognized and credible body, such as the AU’s African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights or the UN Human Rights Office, would lend legitimacy and enhance the scope of the monitoring process. This mechanism could be empowered to deploy observers, hold consultations with civil society, and issue periodic reports that highlight violations and suggest responsive measures. By providing continuous oversight and publicizing findings, such a framework could deter potential human rights abuses and send a clear message to the Burundian authorities that the international community is vigilant and committed to upholding human rights and democratic principles.

Targeted sanctions against individuals and entities implicated in human rights violations and electoral process manipulation should be another cornerstone of the international effort. Diplomatic pressure should be wielded to ensure that the Government of Burundi respects its commitments to international standards for human rights and democratic principles. As a matter of fact, these measures may actually dissuade the government from further actions that undermine the electoral process or violate human rights.

Supporting civil society organizations (CSOs) is crucial, as they play a vital role in election monitoring and human rights advocacy. To this end, international partners should prioritize providing the technical and financial assistance needed for CSOs to fulfill their mandate effectively. Empowering civil society contributes to stronger democratic processes, fostering greater public participation and heightened accountability. However, it is important to consider the regulatory environment in which these organizations operate. In some instances, restrictive laws and policies can limit the ability of CSOs to conduct activities such as civic education or election monitoring. For example, stringent regulations may require excessive registration procedures or impose limitations on foreign funding, hindering CSOs’ operations. Ensuring that these organizations can function without undue constraints is essential for creating an environment where they can actively engage in promoting democracy and holding institutions accountable.

As Burundi reaches this critical juncture in the elections, all forms of political repression and human rights abuses, combined with social discontent, pose formidable challenges. At the same time, an opportunity exists for domestic and international actors to work together to forge an electoral environment that is not only more inclusive, but also more transparent. Upholding human rights and fostering genuine democratic governance are not only crucial for the future of Burundi but also pivotal in ensuring stability in the broader EAC region. Such a commitment can create the way for a peaceful transition and a democratic process that would contribute toward long-term stability that is desperately needed by the people of Burundi.

4.0 Conclusion

In conclusion, the Burundi elections of 2025 will mark a very vital moment for governance and democratic trends in the country. The interplay between entrenched political power, systemic human rights abuses, and societal grievances demands serious attention regarding how to secure an absolutely free and fair electoral process. With such a multi-faceted policy approach to highlight independent electoral oversight, inclusive dialogue, human rights monitoring, and support to civil society, Burundi can hopefully sail through this difficult period into a brighter future characterized by commitment to democratic values and observance of human rights. Only with sustained engagement and proactive measures might the people of Burundi see the cycle of violence and repression broken and, thereafter, a way towards a more peaceful and prosperous future.Top of FormBottom of Form

5.0 References

[1] BBC News, “South Africa: Students Protest Over Fees,” April 20, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-32588658.

[2] Amnesty International, “Burundi: Four Years into Evariste Ndayishimiye’s Presidency, Repression of Civic Space Continues Unabated,” August 8, 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/08/burundi-four-years-into-evariste-ndayishimiyes-presidency-repression-of-civic-space-continues-unabated/.

[3] Africa News, “Burundi: The Main Opposition Party Suspended,” June 7, 2023, https://www.africanews.com/2023/06/07/burundi-the-main-opposition-party-suspended/.

[4] Kenya, Uganda, Burundi score poorly on governance, democratic reforms. The East African, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/kenya-uganda-burundi-score-poorly-on-governance-democratic-reforms-4528006#google_vignette

[5] Bertelsmann Transformation Index, “Burundi Country Report,” 2024, https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/BDI.

[6] ReliefWeb, “Critical Juncture for Burundi: Special Rapporteur’s Mandate Remains Vital,” August 15, 2024, https://reliefweb.int/report/burundi/critical-juncture-burundi-special-rapporteurs-mandate-remains-vital.

[7] Human Rights Watch, “Burundi: Country Chapter,” World Report 2024, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/country-chapters/burundi.

[8] Deutsche Welle, “OHCRC: Burundi’s Elections Aren’t Credible and Free,” May 30, 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/ohcrc-burundis-elections-arent-credible-and-free/a-53513705.