1.0 Introduction

As a global and borderless crisis, climate change remains one of the most pressing global issues of the 21st century. Africa despite being one of the lowest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, it bears the largest brunt of climate change impacts including climate-induced insecurity, aggravated by its large reliance on rain-fed agriculture and natural resources that are highly susceptible to a changing climate. Scientific evidence indicates that our planet is undergoing climatic changes (IPCC, 2023), with temperatures rising, droughts becoming a common phenomenon. Rainfall patterns have also become unpredictable and unreliable. These climate variations have resulted in food insecurity, water shortages, increased socio-economic inequalities, and higher rates of human migration. So are civil wars, and terrorist activities which affects the security of not only East Africa region but also the entire continent.

Studies, such as Bedasa & Deksisa (2024), Cappelli et al. (2024) and Henri et al. (2023) are demonstrating an increasingly imminent linkage between climate change and conflict with the discussions around this nexus gaining traction in different forums including policy-making forums worldwide. Although, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) failed to pass a resolution in 2022 that sought for an integration of climate-related security risks within the UNSC’s work following Russia’s veto on the resolution, the support of the resolution by 113 members of the United Nations (UN), represented the second highest supported draft in the history of UNSC. This underscores the growing recognition of the climate-security nexus as an essential factor in global and regional stability. Further, the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP28) declaration on climate, relief, recovery, and peace, marking a historical acknowledgement of the nexus between climate change and conflict, signifies a big step towards influencing policy and collective efforts in addressing the issue amidst rising geopolitical tensions (COP28UAE).

Regionally, the African Union’s launch of the African Climate Security Risk Assessment (ACRA), marks a great milestone in addressing the various impacts of climate change on security in Africa. This initiative provides a crucial platform for generating more evidence and a comprehensive understanding of the issue. It offers a contextual perspective that can inform regional policies and international frameworks, leading to a holistic approach in addressing climate security, and enable its implementation through inter alia, adequate and accessible financing for sustainable security landscapes beyond the region.

Additionally, the East African Community (EAC) Climate Change Policy offers a regional framework to tackle climate-related issues, including those that lead to conflict. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Climate Adaptation Strategy (2023-2030), on the other hand, provides a framework for coordinated efforts to improve resilience and adapt to the effects of climate change in the Horn of Africa (IGAD, 2023). Such regional efforts play a crucial role in developing a unified strategy to address challenges caused by climate change and promoting sustainable climate security and development.

Despite these efforts, there is still much work to be done to expedite the integration of climate security into policy frameworks, particularly within the international climate change law. This is necessary to enable proactive and anticipatory strategies for addressing climate security in the face of a rapidly changing climate beyond Africa, as articulated by ACRA.

In this context, this commentary delves into the relationship between climate change and conflict in East Africa, aiming to provide a solid foundation for the discussion. This is achieved by highlighting several cases that demonstrate the urgency of resolving these issues through mainstreaming of relevant policies, strategic actions, and frameworks. This includes the integration of climate and conflict early warning and action systems across the continent.

1.1 Perspectives from the region

The State of the Climate in Africa 2020 report highlights that Africa is experiencing ongoing warming, rising sea levels, floods, droughts and landslides with related devastating consequences. Additionally, the glaciers in eastern Africa are rapidly shrinking and are expected to completely melt soon. This indicates a looming and irreversible change to the Earth system (WMO, 2021), in the absence of adequate and holistic climate actions. The changing climate has resulted in increased security vulnerabilities in Africa, characterized by a progressively complex correlation between climate change and conflict, influenced by several factors. Studies suggest that climate change does not directly cause conflicts, but rather intensifies the likelihood of conflicts by magnifying existing vulnerabilities such as population growth and urbanization, socioeconomic inequality, and regional tensions (Cappelli et al., 2024).

The Integrated Climate Security Framework (ICSF) emphasizes the significance of understanding the effects of climate change on peace-security landscapes in order to develop holistic and targeted solutions. ICSF emphasizes that access to natural resources and livelihoods are important aspects through which climate change impacts can contribute to an increase in the risk of conflict (Pacillo et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2024; WMO, 2021). The East Africa region, like the rest of the continent, predominantly depends on agriculture as its mainstay livelihood. Yet, this activity is susceptible to environmental changes such as water scarcity, decreased productivity, and the depletion of grazing areas. As a result of climate change, agricultural productivity growth has declined by 34%, which is the highest compared to other regions worldwide since 1961 (WMO, 2023).

The decrease in agricultural output resulting from climate change exacerbates the occurrence of food insecurity and intensifies competition for these resources in the region. As communities compete for these dwindling resources and adapt to changes, social unrest escalates, leading to instances of violent conflicts (Bedasa & Deksisa, 2024). The anticipated decline in precipitation and its increasing unpredictability pose a significant and enduring challenge for communities. This has consequences for ongoing conflicts, civil unrest caused by drought, competition for resources, and disputes over migration between herders and farmers. These impacts disproportionately affect the vulnerable communities in the region (WMO, 2023).

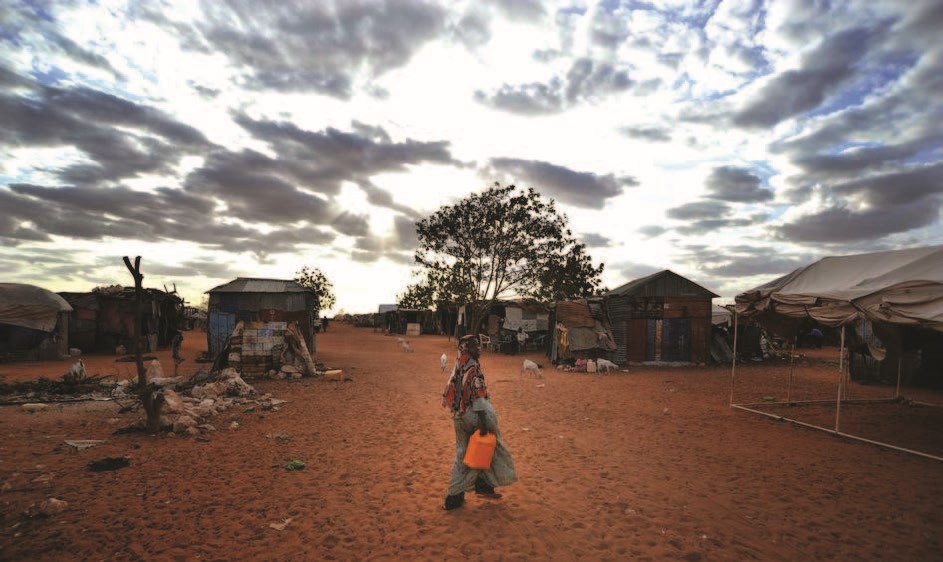

In Kenya, the tensions in the northern part of the country, dominated by pastoralism as the main economic activity, arise from a longstanding competition over land and livestock between semi-nomadic pastoralist communities such as the Pokot, Samburu, Maasai, Tugen, and Turkana. These tensions, which have been ongoing for decades, involve disputes over access to pasture, cattle raids, and alleged historical land issues (International Crisis Group, 2023). In its assessment, Integrity (2024), observed that climate change was one of the key factors exacerbating tensions in the region. It identified among others, the unpredictable and decreasing rainfall, occurrence, and severity of droughts, combined with the increased development on land, limited availability of grassland, water and loss of livestock in the region (Integrity, 2024; International Crisis Group, 2023).

Recently, devastating drought in the Horn of Africa resulted in the loss of approximately 2.5 million cattle over a three-year period from 2020 to 2022 for herders in northern Kenya, wiping out this key livelihood (ibid), with implication for increased cattle theft and violent clashes. The scarcity of grassland and water often compel herders to expand their search for these resources including letting their livestock to graze on commercial farms and private ranges driving conflict between herders, landowners, and security forces, as well as clashes between security forces and cattle raiders threatening the region’s security. For instance, the intrusion of herders into the Laikipia Nature Conservancy in 2021 caused a violent outbreak. Related resource conflicts claimed approximately 240 lives in the region (International Crisis Group, 2023). Despite the intervention by the army and police, the region experienced some stability mainly during the August 2022 elections that saw the region’s security increased (ibid).

In Uganda, a similar pattern of conflict is replicated, as Twinomuhangi et al. (2022)’s study links the forceful migration of thousands of people, climate change, and environmental degradation. In their study, Twinomuhangi et al. (2022) found out that slow and rapid climatic and environmental changes largely influenced the human migration patterns in eastern Uganda. As floods and landslides destroyed livelihoods, the affected population sought alternatives in other areas. This strained existing resources, with WMO, 2021 reporting over 1.2 million climate disaster-related (floods, storms and droughts) displacements in the East and Horn of Africa, with implication for resource use conflicts with the host communities.

In Karamoja of northern Uganda, herders and communities fight frequently over pasture and water worsened by long droughts (APaD, 2024; Wennström, 2024). Climate variabilities, specifically, have subjected pastoralists and agro-pastoralists to the detrimental consequences of livelihood losses, including crop failure and livestock deaths, resulting in famine and loss of human life. The difficult conditions have caused unanticipated migration, notably of nomadic herders from Turkana, Kenya, into Uganda and Karamojong herders into Sebei, Teso, and Acholi, causing resource use conflicts. Within the region of Balalo in Northern Uganda, there is a recurring occurrence of pastoralist groups from South Sudan crossing into Uganda with the intention of raiding livestock. This activity has resulted in intense and violent disputes between the landowners and the pastoralist groups (Saferworld, 2023). The permeable borders have frequently witnessed the entry of illicit small firearms, and weapons into the country, where they are used for raiding and killing.

Additionally, drought has reduced harvests, pushing food prices in not only Uganda but throughout East Africa. This presents potential for gender-based violence particularly in households where family heads are unable to provide for their families. Massive crop failures due to prolonged drought in May and July 2022 raised food prices, with a kilo of sesame seeds for instance selling for 12,000 Ugandan shillings in July 2022, up from 6,000 in April 2021 in Gulu, Northern Uganda.This occasioned food insecurity in households, increasing gender-based violence over the use of limited food. Corroborating this observation, a previous study by FAO noted an increase in physical violence between May and June when households experienced food shortages in Uganda, a likely scenario for the rest of the region.

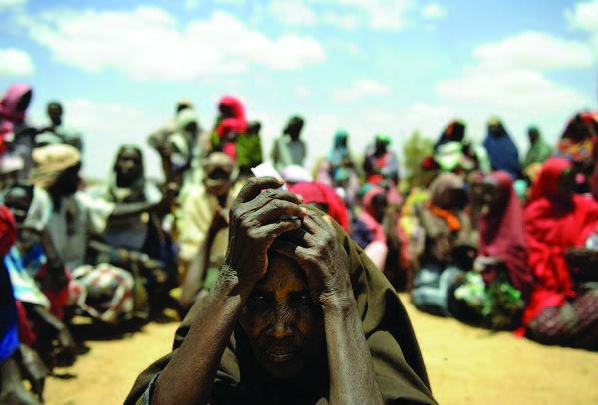

Somalia is no exception to climate-induced tensions and violence. A study by Regan & Young (2022) revealed a positive correlation between annual decreases in mean precipitation and terrorism activities, stressing that reduced rainfall may exacerbate situations resulting in conflict and violence. Similarly, Maystadt & Ecker (2014) found strong evidence that more intense and longer-lasting droughts led to an increase in violent conflicts in Somalia. The prolonged period of droughts has compelled the affected populations to migrate, with Reliefweb reporting that nearly 1.3 million people were displaced by the end of September 2023 and approximately 8.3 million facing a similar crisis or worse acute food insecurity by June 2023. In 2022, the country’s devastating drought following five consecutive failed rainy seasons saw the al-Shabaab militants impose harsh taxes and blockades, targeting food and water.This spurred resentment against the group in certain vulnerable regions, threatening peace and security, and stressing climate change’s impacts as a threat multiplier that creates conditions where violent groups thrive (Charalampopoulos & Feofilovs, 2023).

In South Sudan, four years of flooding adversely affected two-thirds of the country, compelling its population, including ethnic groups such as the Dinka, to acquire arms to protect their herds from raids as they moved in large numbers to the Equatoria region. This heightened tension with the host communities. In places like Darfur and Gezira, where there were already conflicts, it was challenging for herders to move around in search of pasture for their livestock. Such restrictions become a recipe for violent conflict, particularly when herders encountered the farmers competing over limited resources during the onset of rains (FOA, 2024).

The aforementioned conflicts are poignant examples of how climate change aggravates existing vulnerabilities and tensions, threatening peace and security in the region, with a similar trend in the rest of the countries in the region. Without holistic measures conceived, created, and implemented with impacted communities to address environmental and socioeconomic causes of conflict, violent conflicts over decreasing resources are expected to escalate with the fast changing climate dynamics.

2.0 Conclusion

The intricate interaction between climate change and conflict in East Africa is undeniable, as the changes put significant strain on the region’s economic and social fabric. The rapidly changing climate patterns are exacerbating pre-existing vulnerabilities in the region, which heavily relies on agricultural and natural resources. The rising resource use competition for the dwindling resources poses a threat to peace and security beyond the region. Climate change is increasing the probability of violence and instability by acting as a stimulant for threats. An urgent global recognition and comprehension of the imminent link between climate change and conflict and adoption of a systems-thinking approach that emphasizes integrated strategies for peace, security and sustainable development in alignment with both regional and global goals are indispensable.

Notably, peace and security frameworks in the region must include climate mitigation and adaptation strategies to strengthen the regions adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change and related conflict risks. By integrating climate concerns into security policies, conflicts can be avoided before they escalate. In addition, cooperative frameworks that involve all relevant stakeholders, such as state and non-state actors including local communities in the region are needed to ensure equitable access and sustainable use of transboundary resources like water, pasture, and migratory routes, reducing the risk of conflicts and strengthening regional stability and cooperation.

Moreover, the establishment and allocation of resources to strengthen existing peace committees, comprising of governments, local communities, and civil society organizations, are crucial for resolving conflicts including those arising from resource use and forced migrations. This will enable the active involvement of all relevant actors in decision-making processes, guaranteeing that peace committees also include marginalized groups. This strategy is in line with the overarching objective of promoting inclusivity and enabling local participants to assume responsibility for peace processes, hence enhancing the credibility and durability of peace efforts as envisioned by Kenya’s and regional Peacebuilding Architecture.

Equally, increased government and development partner investments in climate-resilient agricultural practices and livelihood diversifications will reduce the reliance on climate-sensitive sectors by affected populations, easing resource competition and mitigating potential conflicts in the region.

Considering the positive political good will demonstrated through the declaration on climate, relief, recovery, and peace at the COP 28 (COP28U AE), this commentary anticipates further discussions and commitment at COP 29 towards improving global collaboration to address security risks caused by climate change, particularly in vulnerable regions such as Africa and Eastern Africa in particular. It is important to emphasize the necessity of increased financial support for climate adaptation and resilience-building initiatives in conflict-stricken regions. Additionally, there is a need to expedite the integration of climate considerations into peacebuilding and security planning and development of more robust international frameworks to oversee the management of transboundary resources and enhance efforts to establish peace in response to climate change.

3.0 References

APaD. (2024). Conflict and Climate Assessment Report: Karamoja Cluster (p. 42). The Agency for Cross Border Pastoralists Development (APaD).

https://hornresiliencelearning.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Conflict-and-Climate-Assessment-Karamoja.pdf

Bedasa, Y., & Deksisa, K. (2024). Food insecurity in East Africa: An integrated strategy to address climate change impact and violence conflict. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 15, 100978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2024.100978

Cappelli, F., Costantini, V., D’Angeli, M., Marin, G., & Paglialunga, E. (2024). Local sources of vulnerability to climate change and armed conflicts in East Africa. Journal of Environmental Management, 355, 120403.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120403

Charalampopoulos, N., & Feofilovs, M. (2023). Climate Change: A Multiplier for Terrorist Activity. CONECT. International Scientific Conference of Environmental and Climate Technologies, 149. https://doi.org/10.7250/CONECT.2023.117

Henri Aurélien, A. B., Bruno Emmanuel, O. N., Hervé William, M. A. E., & Thierry, M. A. (2023). “Does climate change influence conflicts? Evidence for the Cameroonian regions.” GeoJournal, 88(4), 3595–3613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10824-7

IGAD. (2023). THE IGAD CLIMATE The IGAD Climate Adaptation Strategy (2023-2030) (p. 184). Intergovernmental Authority on Development Centre of Excellence for Climate Adaptation and Environmental Protection (IGAD CAEP). https://igad.int/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IGAD-Climate-Adaptation-Strategy-2023-2030-.pdf

Integrity. (2024). Northern Kenya Violence and Confict Assessment (p. 74). USAID/Bureau for Conflict Prevention and Stabilization. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-05/20240202_PEARL-Kenya-VCA_V3.pdf

International Crisis Group. (2023). Absorbing Climate Shocks and Easing Conflict in Kenya’s Rift Valley. International Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/b189-kenya-climate-shocks_1.pdf

IPCC. (2023). Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

Maystadt, J.-F., & Ecker, O. (2014). Extreme Weather and Civil War: Does Drought Fuel Conflict in Somalia through Livestock Price Shocks? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96(4), 1157–1182. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aau010

Pacillo, G., Liebig, T., Carneiro, B., Medina, L., Schapendonk, F., Kenduiywo, B., Craparo, A., Basel, A., Minoarivelo, H. O., Villa, V., Belli, A., Caroli, G., Madurga-Lopez, I., Scartozzi, C., DuttaGupta, T., Ramirez-Villegas, J., Estrella, H. A., Mendez, A. C., Resce, G., … Läderach, P. (2023). Measuring the climate security nexus: The Integrated Climate Security Framework. https://doi.org/10.31223/X5795K

Regan, J. M., & Young, S. K. (2022). Climate change in the Horn of Africa: Causations for violent extremism. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 16(2), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2022.2061032

Saferworld. (2023). There’s absolutely no rain, I don’t know what to do next”: Perspectives on climate change and conflict in Uganda and Kenya. https://www.saferworld-global.org/resources/news-and-analysis/post/1002-athereas-absolutely-no-rain-i-donat-know-what-to-do-nexta-perspectives-on-climate-change-and-conflict-in-uganda-and-kenya#:~:text=In%20Balalo%20in%20Northern%20Uganda,used%20against%20animals%20and%20people.

Twinomuhangi, R., Sseviiri, H., Mfitumukiza, D., Nzabona, A., & Mulinde, C. (2022). Assessing The Evidence Migration, Environment & Climate Change Nexus in Uganda (p. 92). International Organization for Migration.

https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1411/files/documents/assessing-the-evidence-migration-environment-climate-change-nexus-in-uganda.pdf

Wennström, P. (2024). Cattle, conflict, and climate variability: Explaining pastoralist conflict intensity in the Karamoja region of Uganda. Regional Environmental Change, 24(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-024-02210-x

WMO. (2023). State of the Climate in Africa 2022 (WMO-No. 1330). World Meteorological Organization (WMO). https://library.wmo.int/records/item/67761-state-of-the-climate-in-africa-2022

Zhu, H., Zhang, Q., & You, H. (2024). A Water–Energy–Carbon–Economy Framework to Assess Resources and Environment Sustainability: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Energies, 17(13), 3143. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17133143

https://reliefweb.int/disaster/dr-2015-000134-som

https://southsudan.crisisgroup.org/https://www.usip.org/publications/2017/05/how-drought-escalates-rebel-killings-civilians

https://www.cop28.com/en/cop28-declaration-on-climate-relief-recovery-and-peace

https://www.nscpeace.go.ke/news-blog/171-kenya-s-peacebuilding-architecture-review-2023