1.0 Introduction

William Ruto is a bright, hardworking, man with his hands in many policy pots. At times, his policies contradict each other due to changing revolutionary dynamics in world affairs that are linked to political economy. This makes it difficult for him to balance political desires with economic realities and it occasionally lands him in policy trouble. This commentary seeks to appraise Kenya’s Foreign Policy outlook under the Kenya Kwanza government.

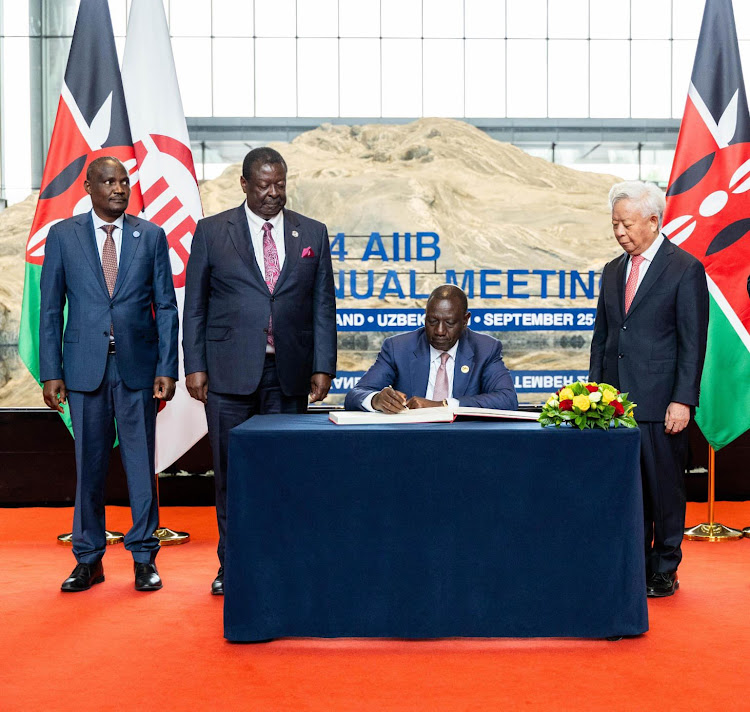

He has been in office for roughly two years and has, more than other leaders in or out of Africa attracted a lot of attention. He likes attention, especially the international ones and does his best to remain in good books with the West while maintaining ‘strategic ambiguity’; he initially seemed to succeed. He was, for instance, so well received in the West as the likely leader of the African continent that he actually took on to talking for the collective Africa to the rest of the world. He travelled the world widely, averaging three foreign trips per month, as the domestic scene continued to deteriorate. He also appeared to be hostage to such forces as the IMF, the World Bank, and what he called ‘friends’. In June 2024, the travels virtually came to a temporary two month halt due to Generation Z or Gen Z demonstrations. This damaged his ‘international reputation’.

Signs of trouble for Kenya’s foreign policy were clear on the inauguration day. First, Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua showed his lack of sense of occasion by disproportionately attacking former President Uhuru Kenyatta. The visiting African heads of state and government pointed out that they had not come to Kenya to witness domestic infighting. Second, after a visit by the Moroccan minister for foreign affairs, Ruto decided to expel the Sahrawi envoy from Kenya, contrary to the AU position on Western Sahara. The boomerang to that knee-jerk decision, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs pointing out that Kenya did not conduct foreign policy through twitter, forced Ruto to beat retreat on expelling the Sahrawi diplomats [Munene 2022].

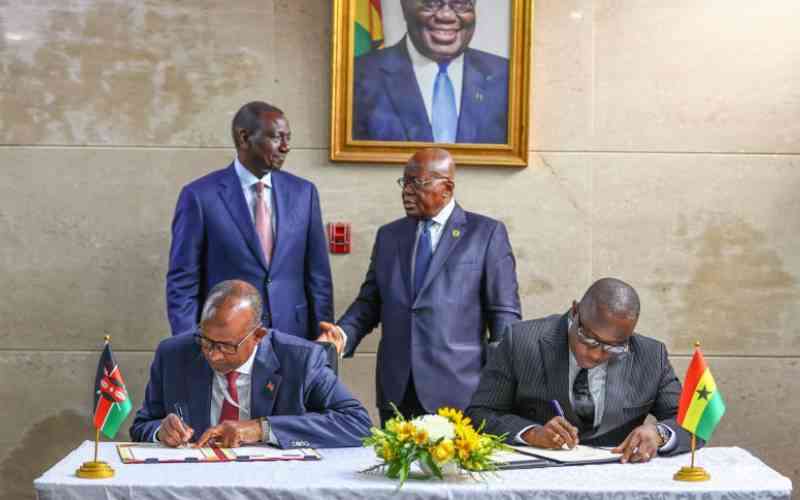

Despite the initial diplomatic weaknesses, Ruto showed determination to make a mark on global issues and probably outshine Uhuru Kenyatta. He outdid Uhuru in global trips and seemed to strike the right cord in the Global South. His ‘strategic ambiguity’, seeking to gain from all sides in geopolitical disputes, helped him seem to overcome initial drawbacks [Mutambo 2022]. He made effort to promote peace and started touring the region to explain his agenda [Mutambo and Anami 2023]. He complained about extra-continental powers summoning African leaders for ‘Summits’ to listen to one person and vowed not to attend such summits, and even called for ‘dedollarisation’ in world trade. On matters trade, the December 2023 Kenya-EU economic partnership agreement, EPA, designed eventually to open up the European markets for Kenyan goods [Pichon 2024] has good potentials for the country . He sounded like a good voice for the region and the Global South (Eickhoff, 2024).

Questions, however, arose about his acumen in world political dynamics and his position consistency. Having vowed not to attend ‘summits’ for African leaders that extra-continental powers like calling, he often finds reason to attend such summits; the latest being the September 2024 one in Beijing with roughly 40 other African leaders. He appeared quick to comment graphically on evolving events. Commenting on Sudan, telling the ‘generals’ to ‘stop the nonsense’, he was later linked to the United Arab Emirates supported RSF leader Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo alias ‘Hemedti’. The remarks and linkage backfired badly on Ruto’s quest for IGAD and African leadership. He was quick to endorse the Israeli position in Gaza before comprehending the full impact of what was taking place, thereby appearing as if Kenya condoned the unfolding ‘genocide’ (cf. Dutta, 2024). He, in a manner pleasing to the French and the Americans, reacted too quickly to upheavals in the Sahel region, dismissing them as ‘coups’ and calling for reinstatement of removed ‘leaders’. Like Emmanuel Macron of France, Ruto ‘condemned’ the coup in Niger which, he said, was a “serious setback for Africa.” He missed the point that Niger was more than a coup; it was a ‘revolution’ that removed French neo-colonialist overbearing.

While getting out of touch with geopolitical developments in the Global South, Ruto seemingly got into US President Joe Biden’s geopolitical web in which Biden was searching for an agreeable African leader. Ruto’s seeming wish to be in good books of the West, therefore, made him attractive especially as he finalized discussions about Kenya sending police officers to Haiti, and the Americans paying for it, amidst stiff reservations. Although the Kenyan courts found the exercise improper, he still went ahead with it on the strength of a ‘bilateral agreement’ between Kenya and Haiti[Muia 2024]. He was rewarded with invitations to attend meetings in Rome and Geneva, probably as the African leader, essentially to endorse Western positions on Ukraine; he did not disappoint. He also received the Biden praises, was given a US state visit, and had Kenya designated as a US ‘Non-NATO Ally’ to strengthen US defense presence in Kenya and the Eastern Africa region. It was the high point of Ruto’s global presence.

In the midst of all that diplomatic accolades, however, were domestic troubles that spoiled Ruto’s image as leader in the Global South. When Kenyans complained about extravagant foreign trips, especially the US state visit, he explained that his foreign ‘friends’ had paid for his luxury jet. . Questions then arose as to how much control such ‘friends’ have on Kenya’s president. While in the US, he defended high taxation as necessary, amidst growing resistance. He insisted on the Parliament passing the Finance Bill 2024 with obnoxious provisions in it as some MPs used offensive language on critics. High tax on bread, argued one MP, would help to reduce obesity and that one should not drive cars if he cannot afford annual taxes. Since the collective attitude in the Ruto government offended common sense, therefore, the simmering public resentment expanded like a balloon that needed a prick to deflate it. The Generation Z, or GenZ, after the passing of the Finance Bill 2024, was the pin that pricked the Ruto balloon.

Kenya’s youth led revolution of attitude reverberated globally and left pundits wondering who they were. They were very young children or about to be born in 2003 when Mwai Kibaki became president and ordered all children to go school by saying “Watoto Wasome”, with no fees demanded. They received good education, were exposed to critical readings, grew up in the digital explosion, and became critical thinkers. They noticed and were baffled by the pain, docility, and diminishing sense of hope in their parents. With nothing to lose, and with evidence of malpractices, they decided to question government policies that made no sense. Knowing nothing about atrocities associated with the Daniel arap Moi’s era, they were fearless as they questioned extravagance by a few people squandering public resources, foreign control of public policy, high incompetence and corruption, and high taxes that created poverty instead of wealth production. Their strength was in stressing nonviolent demonstration, constitutionalism, the spirit of the national anthem in Kiswahili, and serious public participation in law making.

In the process, Kenya was politically transformed and descended into an object of geopolitical curiosity in search of itself. No longer able to advise other African countries how they should behave, Ruto stopped foreign trips and even missed a key AU meeting in Accra where he was to give a report on reforms in Africa. Outside Kenya, the GenZs became inspirational to young people in other African countries who suffer similar insensitivity from their governments. Ruto was forced to rethink domestic and foreign policies in a transformed Kenya.

In facing the new domestic and international environment, Ruto appears to have adopted political strategies that could win. First was to deflate the GenZ balloon by appearing to give concessions by withdrawing the Finance Bill 2024, dismissing most of the cabinet secretaries, and engaged in cyber discussions. Second, was to infiltrate the youth who had showed power that was visibly a threat to the political class, whether in government or in the opposition. The subsequent coming together of the political class was reportedly responsible for the emergence of youngish goons as ‘demonstrators’ with the intended effect of discrediting the GenZs. This made the initial revolution of attitude appear like orchestrated anarchy so as to lose public support. Third, Ruto embarked on reclaiming the prominence that he seemingly lost in the one month of the GenZ revolution which might enable him to rebuild his desired international posture. He thought he could rebuild Political Capital and create sense of stability by retaining most of the old cabinet and bringing in some prominent people in the Opposition, particularly ODM.

Although Ruto is determined and is appears to have weathered the storm, in the belief that he has deflated the GenZs, it is necessary for him to rethink strategy in order to confront external challenges that increase his foreign policy difficulties. Nowhere do the prospects look bright with the United Nations already expressing deep concern over police handling of the demonstrators. Having blamed Russia and America for the Gen Z uprising [Mkawala and Chege 2024; Oruta 2024], mending fences might be hard. The US has stopped praising him and is instead advising him on the rights of the youth. As a result US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken called to tell Ruto to treat the demonstrators in humane ways. In addition, a new administration will take over in Washington in January 2025 and since it may not follow the Biden Africa policies, Ruto needs to adopt fresh approaches to the United States. There is a new government in Britain which is likely to pay more attention to the Caribbean, India, and South Africa than to Ruto’s desires for recognition as world leader. He might want to evaluate and then leverage whatever tools Kenya has that would make London listen to Nairobi.

African leaders, especially those facing possible youth upheavals, might want to avoid his mistakes. Divided into assorted ideological camps, they are unlikely to entertain Ruto’s desires as their spokesman. The likely distancing of the West from a Ruto that is domestically increasingly unstable is a warning not to be too cosy to Western enticements. Given that Kenya is not even in the top tier of the Global South influence pecking order, coming below South Africa and North African countries, its domestic tribulations further reduce its continental leadership potential. This reality makes its bid to front Raila Odinga as AU Commission Chairman problematic. It is Kenya’s image and Ruto’s dream of recognition as the continent’s trouble shooter and ‘peace maker’ that needs repackaging and sprucing up. Kenya’s foreign policy Mr. Fix It, Musalia Mudavadi, will have to look for extra energy in order to allay domestic fears that Kenya has lost its sovereignty to unknown foreign entities. The impression that ‘officials’ have ‘sold’ critical Kenyan institutions to foreign entities, for a fee going to the ‘officials’ is part of the reasons that the GenZs gained popularity. Senator Richard Onyonka, a former assistant minister for foreign affairs, reinforced that impression by asserting that someone in authority ‘virtually’ gave away Jomo Kenyatta International Airport to the ADANI of India, with contestation around the deal transparency[1]. This puts Mudavadi’s credibility on the line, despite his assertion in Parliament that the airport has not been ‘sold’. The corruption perception, therefore, creates problems for him to persuade other countries that Kenya is ready to interact in honourable and uncompromising ways. It is an impression that Ruto, Mudavadi, and Kenya have to overcome to have a standing anywhere.

Note: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author.

2.0 References

[1] https://www.occrp.org/en/scoop/documents-reveal-details-of-adani-groups-controversial-bid-to-run-kenyas-largest-airport

Aggrey Mudambo and Luke Anami, “Kenyan President Ruto outlines his regional diplomatic strategy,” The Citizen, January 8, 2023

Aggrey Mutambo, “William Ruto diplomacy gamble: Riska and opportunities,” Nation, September 26, 2022

Amos Khaemba, “Wilson Sossion says Gen Zs are Product of Mwai Kibaki’s Free Education: ‘Highly Informed’” https://www.tuko.co.ke/kenya/556154-wilson-sossion-gen-zs-product-mwai-kibakis-fr… July 23, 2024

Basilloh Rukanga, “William Ruto and Bola Tinubu: Africa’s ‘flying presidents’ under fire,” BBC News 19 February 2024

Brian Ngugi, “Ngugi wa Thiong’o: Ruto is selling the country cheap,” The Standard, May 30, 2024

Brian Obara, “Ruto’s Big Flaw? Lack of Imagination,” Voices, July 25, 2024

Brian Oruta, “Foreign powers behind Gen Z protests, Isaac Mwaura alleges,” The Star June 23, 2024

David Pilling, “Kenya’s populist has misread the popular mood,” Financial Times, July 17, 2024.

Eric Pichon, “Economic Partnership Agreement with Kenya(East African Community)” EPRS: European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2024

Karoline Eickhoff, “Winning Hearts and Minds Abroad or at Home? Kenya’s Foreign Policy under William Ruto’’ Policy Brief 24 March 2024

https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/policy-brief-24-winning-hearts-and-minds-abroad-or-at-home

Khasai Makhuto, “Taking Charge: Gen Z Leads Historic Protests in Kenya,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, CSIS, June 27, 2024

Macharia Munene, “PM’s task to reset ‘new Britain’ in changing world,” Sunday Standard, July 14, 2024

Macharia Munene, “William Ruto starting badly in Africa: The Sahrawi blunder,” Sunday Standard, September 18, 2022

Mbui Wagacha, “Kibaki legacy: Thriving economy, free education,” The East African, Saturday, April 23, 2022

Michelle Gavin, “America’s Dilemma: Washington Erred in Embracing Ruto-but Now Must Double Down on Helping Him Succeed,” Foreign Affairs, July 23, 2024

Mohan Dutta. Resisting an unfolding genocide: reflections from radical struggles in the Global South. QuarterlyJournal of Speech, 110(2), 294–304, 2024

https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2024.2328588

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, “An Open letter to Kenya President William Ruto,” The African Dream, June 1, 2024.

Oliver Mathenge, “President Ruto’s Jet, diplomacy, trade and UAE push to grow its influence,” Sunday Nation, June 02, 2024.

Sharon Wanga, “US Secretary Blinken tells Ruto to respect youth and civil society,” The Standard, July 27, 2024

Steve Mkawale and Daniel Chege, “Ruto accuses Ford Foundation of sponsoring Gen Z Protests in Kenya”, July 15, 2024

The East African, “Friend or foe? President Ruto admission exposes UAE hand in Horn of Africa,” Saturday, June 1, 2024

The Economist, “Kenya’s deadly ‘Gen Z’ protests could change the country,” The Economist, July 9, 2024

Waikwa Maina, “Auditor report reveals rampant corruption, mismanagement in county assemblies,” The Nation, April 16, 2024

Wycliffe Muia, “Kenyan President Ruto says Haiti mission to go ahead despite court ruling,” BBC News, January 31, 2024