1.0 Introduction

South Sudan, the youngest sovereign state in the world, became independent on 9th July, 2011 following the secession of the “Autonomous South Sudan” from the Republic of Sudan. Located at the North- Eastern part of Africa, it is a land locked country, with 619, 745 sq. kms in size and a population of 10.91 million people (World Bank, 2022). It shares boundaries with the Republic of Sudan, Central African Republic, Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The geopolitical significance of South Sudan does not only stem from the fact that some of its neighbors are also undergoing various degrees of civil conflict, but also that it shares the strategic River Nile with Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Sudan and Egypt. It is a member of the East African Community (EAC), the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and, of course, the African Union (AU). With a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of only US$ 6.9 billion (IMF,2024), South Sudan is one of the least developed and poorest countries in the world despite possessing enormous natural resources including vast oil reserves and lush and fertile savannah lands.

South Sudan is home to several ethnic groups. The two major ethnic groups, the Dinka and the Nuer account for about 40% and 15% respectively (CIA Fact Book, CIA/State.gov, 2024). Political mobilization and organization, including by political parties and military factions have been generally along ethnic lines. It is instructive that the main protagonists in the power struggle in the country, President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar belong to the Dinka and Nuer respectively. This is important because of the high levels of ethnicization of politics and politicization of ethnicity in South Sudan. About 60% of South Sudanese are Christians. Others are either Muslims (6.2 %) or Animists (32.9%). It is important to note that the major motivation for the historical resistance before independence were the attempts by successive foreign rulers to “Islamize” the region. The Islamization project was initiated by Egyptians who invaded the region on behalf of the Ottoman Empire in the 1820s. In 1899, the British partnered with Egypt to establish a condominium over Sudan. Islamization of the south intensified when the colonial government decided to use government officials from the Arab North to govern the largely Christian and animist South. The Northerners, in collusion with the colonial officers, began to ‘Arabise” the South. The struggle for self-determination in the South continued even after independence was granted to Sudan in 1956. This was because, all the post-independence governments, both civilian and military, continued with the Arabization and Islamization policies. Armed rebellions led to two civil wars (1956 – 1972 and 1985 – 2005). Decades of oppressive “foreign occupation” and rule by colonialists and the Northerners and the resultant civil wars left the South with weak political and social institutions and systems.

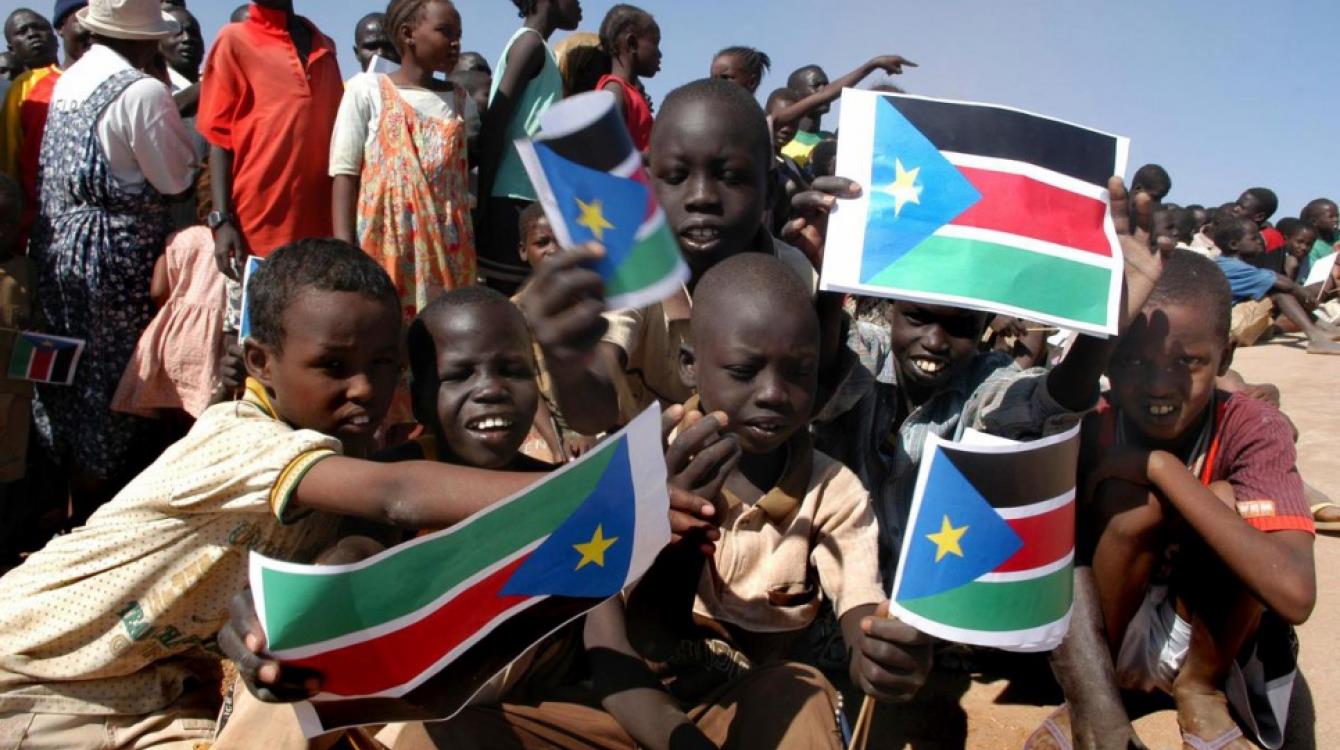

The Republic of South Sudan was birthed by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005 at the conclusion of mediated peace talks between the leadership of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Government of Sudan. The former had fought for self-determination and freedom of the southern Sudanese who, according to them, had undergone decades of discrimination and injustice meted on them by both the colonial and post-colonial regimes that had seemed to favor the Arab North at the expense of the black community of the South. The CPA brought an official end to the 20-year civil war and re-created the “Autonomous South Sudan” but with an “Escape Clause” that gave the South Sudanese the right to secede after six years if they so wished, albeit after a plebiscite. In 2011, an overwhelming majority supported secession in a referendum. However, since independence, the country has experienced one political crisis after another with the most serious one being triggered by what the government called an “attempted coup” in 2013, only two years after independence.

Despite several peace initiatives by both domestic and foreign actors, the country remains politically volatile with several political factions emerging from time to time. Despite several attempts to hold general elections, the South Sudanese have never had the chance to choose both local and national leaders under universal suffrage. The government in power since independence remains a transitional one to date. Inter-communal violence and intermittent violent clashes between the many military factions and militias at national and local levels have led to displacement of people with some fleeing to neighboring countries. The problems and crises that the young country has faced since its independence are the mark of state fragility whose origins go back several decades, especially from the colonial era. The Southern Sudanese polity has exhibited weak political structures and institutions since the colonial era when it was under the British as part of the Sudanese condominium.

The aim of this commentary is to give an account of state fragility in South Sudan, highlighting its implications for both domestic and regional peace and making some policy recommendations on how the situation could be ameliorated.

The on-going post-independence problems in South Sudan have been caused primarily by the lack of political will by various stake holders and parties to respect and implement provisions of several peace agreements they have negotiated. In some cases, the provisions have been violated by various parties. The CPA itself has not been fully implemented. Indeed, disagreements over its implementation have, to a large extent, contributed to the current crisis. Different parties, civil society, and other stake holders have sometimes interpreted certain CPA clauses differently. The 2018 agreement that was supposed to end the crisis caused by the 2013 alleged “coup attempt” by Riek Machar was not fully implemented. It, however, established a Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) with Kiir as president and Machar (leader of SPLM-IO) as first Vice president. This has led to the unnecessarily prolonged transitional period. It is now almost 13 years since independence and the South Sudanese have never had the chance to elect their leaders. President Kiir himself assumed leadership of the “autonomous Southern Sudan” after the death of the then leader, John Garang. He automatically became President of the transitional government on independence in 2011, without elections as per the CPA. Before elections could be held, however, the 2013 crisis set in, putting plans for elections in abeyance. According to the 2018 agreement, elections were to be held within 6 months. This did not happen. A new date was given for 2023. The elections were again postponed indefinitely. The major reason for the perennial postponements has always been claims by various parties and stakeholders that the environment has never been conducive for free and credible elections. Intrinsically, however, the failure to hold elections can be attributed to lack of political will of the major players to ensure full implementation of the provisions of the several aborted agreements, provisions that would create an enabling environment for credible elections.

The transitional government may soon lose legitimacy and support from the citizens should the situation remain as it is. The power wrangles between the main protagonists, Salva Kiir and Riek Machar, shall continue so long as free and credible elections are not held soon. As the stalemate in Juba continues, the military factions and militias in other parts of the country will continue to wreak havoc, resulting in deaths and displacements. Perhaps it is this concern that may have led Kiir’s government to schedule elections for December, 2024.

To avoid further deterioration of the situation, certain measures need to be taken by domestic and external actors and stake holders. On the dispute over the recently released election schedule, the AU, IGAD, UN, EAC should provide their multilateral platforms to bring together to negotiate and strike an agreement on the election time table. The electoral programme developed by the National Elections Commission (NEC), as contentious as it has become, should form the basis for negotiation. Consensus could be reached on the issues generating conflict. SPLM-in-O and several other stakeholders, especially those that are party to the 2018 Revitalized peace agreement like Real-SPLM and the “Hold Out Groups” (those who refused to sign the 2018 agreement) have argued that the electoral programme is not realistic. They argue that there are some minimums to be met before elections are held, and that they cannot be met by December, 2024, the proposed date for elections. These include the creation of a “Unified Force” through the reintegration of thousands of rebel forces into the national military, resettlement of the Internally displaced persons, facilitation of the return of refugees and the holding of a national census. On the other hand, the Transitional Government of National Unity and the ruling party, SPLM in Government, maintain that elections have to be held to end uncertainty and that the transitional period has been too long. The UN, one of the guarantors of the peace agreements have supported the electoral program, arguing that, even though some of the provisions of the 2018 agreement have not been satisfactorily implemented, observing that a “critical mass” has been achieved in implementation (The East African, April 13 – April 19, 2024, p.5).

There is also need to strike a broad consensus on the election program. This may require that the issues raised by the stake holders be discussed at round table meetings convened by third parties, especially regional organizations like IGAD, AU, UN and EAC, of which South Sudan is now a member and current chair. This is important in order to avoid a post-election fallout that might lead to an escalation of violence. It is important to have the election calendar approved by all stakeholders, if not a majority of them. It may not be possible for all the parties and stake holders to agree on all the contentious issues. However, it is possible for the parties to agree on selected minimum requirements for a fairly free and credible election. The parties could borrow a leaf from Kenya’s Inter-Parliamentary Parties Group (IPPG) elections deal of 1997, that broke a similar impasse of elections for that year.

On the issue of reintegration of military factions into a unified national force, IGAD should appoint a neutral mediator to bring leaders of the factions, including government forces, together to negotiate a new timetable that needs not be tied to the elections schedule. It is instructive that retired General Sumbeiywo of Kenya, recently appointed by President Ruto, on behalf of IGAD, has already managed to persuade a majority of the “Hold Out” groups to begin negotiations with the government of South Sudan in Nairobi. Similar negotiations with other factions are likely to lead to a broad consensus on the issue of the “unified force.”

The EAC is uniquely privileged to play a mediation role. This is because the Republic of Sudan is one of its members, and more importantly, President Kiir is the current chair of the EAC Summit. Kiir’s counterparts in the Summit could collectively and individually engage him.

The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) should be engaged to facilitate the return of IDPS and resettlement of refugees, about 2 million of whom are living in camps in neighbouring countries. However, given the complexities involved in the two exercises, and the intermittent outbreak of violence in some states, the return of refugees and resettlement of IDPS may not have to determine the election timetable.

The US, the AU and the UN security council could give diplomatic support to the negotiations which should be held on each major contentious issue separately but simultaneously.

In conclusion, there appears to be renewed political will on the part of the major parties and stakeholders to break the impasse on the implementation of outstanding issues in the CPA, the 2018 and 2020 agreements. It is particularly encouraging that on 9th May, 2024, President Ruto, launched the UTUMAINI INITIATIVE at a significant meeting in Nairobi that brought together representatives of the Transitional Government led by President Kiir and two other parties in the peace process including leaders of the Real-SPLM and the South Sudan United Front.