1.0 Introduction

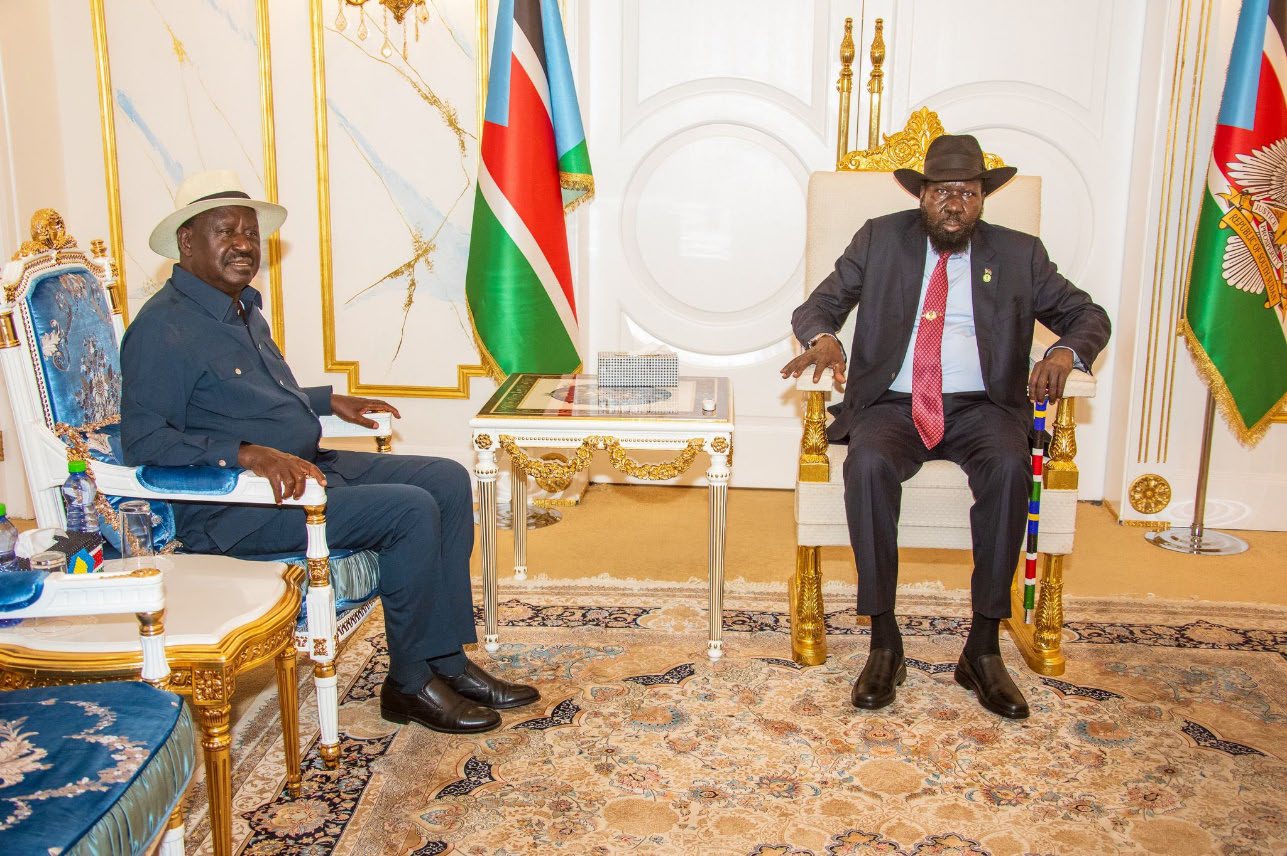

The troubled Republic of South Sudan has sunk, yet again, into an even, more profound crisis in the last couple of weeks. The current situation was triggered by President Kiir’s recent decision to unilaterally replace the governor of the Upper Nile state, General James Odhok, an ally of First Vice President Riek Machar, with his loyalist, General James Koang. On March 18, 2025, Machar withdrew his Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO) from the existing power-sharing arrangement. Kiir responded by placing Machar under house arrest. Tensions have continued to rise with stakeholders in the ongoing peace process raising alarm that, if not nipped in the bud, the crisis could exacerbate the already volatile situation. Kenya’s president, Ruto, the current Chairman of the East African Community (EAC), of which South Sudan is a member, sent an envoy, Raila Odinga, on a fact-finding mission to Juba. Odinga, however, could only meet with Kiir as he was denied the chance to meet Machar. President Museveni of Uganda has also visited Juba. The Inter-Governmental Authority for Development (IGAD), the guarantor of the ongoing peace process, has convened an emergency meeting. The international community, led by the UN, has raised the alarm as well. This commentary seeks to discuss the escalating crisis in South Sudan and recommend measures that could assist to bring lasting peace in the country.

The Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS), signed on September 12, 2018, had birthed a Transitional Government of National Unity. It ended the 2013-2018 civil war that had ravaged the young republic that had become independent only in 2011. The agreement provided for a power-sharing arrangement in which President Kiir would share power with Riek Machar’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO) and other smaller political parties. Kiir would remain President with Riek Machar becoming First Vice-President. It was also agreed that appointment and replacement of senior officials like cabinet ministers and state Governors would be made after consultations. Machar has repeatedly complained about Kiir’s unilateral decisions, especially on appointments and other issues in violation of the provisions of the agreement.

The latest crisis is just one in a series of many challenges South Sudan has faced since its independence. There have been intermittent violent conflicts between ethnic communities in a country awash with several ethnic militias. There are several rebel movements at sub-territorial, regional and provincial levels. Jonglei, Upper Nile and Equatorial states, in particular, continue to witness violence instigated by warring rebel groups. Power struggles at the national level, especially after the death of Garang, the founder leader of SPLM and the first post-secession President, led to a split SPLM into three factions: the Kiir-led SPLM in government, Machar-led SPLM-In Opposition and the Real SPLM. There are many other splinter political parties backed by armed militias.

The national military has also not been spared internecine wars as top commanders have divided loyalties. The multi-pronged inter-communal, intra-regional, intra-provincial and national power struggles continue to undermine peace and security in South Sudan. Indeed, the South Sudanese had to endure a five-year civil war between 2013 and 2018.

It would seem that South Sudan has had a false start as an independent state. No elections have been held since the 2011 secession referendum that ushered in independence. Many a time, scheduled elections have had to be postponed because of differences between various parties. For instance, elections scheduled for December, 2024 were postponed at the last minute. The failure to grant citizens the opportunity to choose their leaders has undermined the legitimacy of the leadership.

Intermittent internecine wars and violent clashes have seen several Sudanese displaced internally, while others have fled to neighboring countries as refugees. The 2013-2018 civil war alone left thousands dead, one in three people displaced and more than 2 million people fleeing to neighboring countries.

Economically, South Sudan remains one of the poorest countries in the world despite its rich biodiversity with lash Savannah and rain forests. Although the country has huge agricultural potential, it has remained susceptible to frequent famine and hunger. There are also huge deposits of petroleum, gold, diamonds, limestone and silver.

Despite several attempts by domestic and international stakeholders to stabilize the country, peace in South Sudan has largely remained elusive. Several peace agreements have been negotiated only to be undermined and rendered nugatory by parties signatory to them. The current peace process, the R-ARCSS, seemed to hold greater promise but it has also been so systematically violated that it is no longer the beacon of hope it had been. The major question now is: what will it take to bring lasting peace to South Sudan?

First, South Sudanese citizens should be afforded the opportunity to elect their leaders in free, credible and fair elections. This should be the top priority even as regional and international actors strive to solve the current crisis. Elections might produce a fresh leadership cadre committed to peace and stability. Such leadership could be free from the age-old personality differences and mistrust among current leaders. However, the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) as currently constituted may not be trusted by many domestic stakeholders, including SPLM-IO, to organize national elections. So, who should organize elections? The UN should be tapped to organize a national conference or convention bringing together all the stakeholders including community leaders, political parties, religious organizations, and the TGoNU. The UN security council can oversee the work of the convention until elections are held and a new leadership is in place. The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) could be revamped and granted peace enforcement powers to ensure security in the interim period. The convention could turn itself into a constituent assembly with the mandate to write a new constitution and to prepare the ground for national and regional elections to be organized and supervised by the UN.

Second, in acknowledgement of the strong ethnic currents in the power struggles and conflicts in the country, some form of consociational parliamentary democracy within a federal framework could be embraced. Each federal state could have a bicameral legislature with the upper house having representatives from each recognized ethnic group.

Third, the military should have a unified command with a rotational succession plan for senior ranks. Perhaps, Kenya’s Tonje Rules that have brought stability among military officers by establishing predictability in the promotion and retirement in the military ranks could act as a guide.

Fourth, there should be a deliberate plan to depoliticize and de-ethnicize the military and other security agencies. The re-integration plan envisaged by the R-ARCCS should be fully implemented. According to the plan, various military and militias outside the national command were to be demobilized and absorbed into the national military infrastructure.

Fifth, the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) of the African Union (AU) could establish a permanent South Sudanese mission within its Conflict Early Warning System to monitor the situation in South Sudan on a continuous basis. The CEWS could collaborate with other interested parties like the International Crisis Group in this exercise.

Sixth, the regional groupings to which South Sudan belong, especially the EAC and IGAD should deploy the leverage they have to insist on the implementation of the R-ARCSS. It should be recognized that the greater responsibility for implementation lies with the president of South Sudan who is a member of the Summits of the two organizations. If need be, the two organizations could lobby the UN security council to institute urgent measures to ensure compliance by parties to the agreement.

Seventh, should national elections be held, the current crop of the top leadership should be persuaded not to vie. They could be incentivized to do so in many ways: to include assured blanket amnesty and immunity from prosecution for any perceived crimes, plum retirement benefits for themselves and their associates and assignment of honorary diplomatic duties by regional and international organizations.