This brief explores the key underlying issues affecting the port of Mombasa competitiveness and proposes actionable strategies to restore the port’s vitality. Drawing on expert interviews and documented literature, the analysis focuses on challenges such as transport connectivity and the underlying causes of port inefficiency. These encompass capacity constraints, tariff structures and workforce dynamics. The brief recommends infrastructure enhancements, operational optimizations and initiatives to promote workforce diversity and inclusion. Implementation of these measures is essential for revitalizing the port’s role in facilitating regional trade and fostering economic growth in East Africa.

Introduction

Recent studies conducted by key development institutions such as the World Bank and the African Union have underscored the pivotal role of trade in driving economic performance in Africa and Asia, highlighting its potential to yield substantial gains in economic growth.[1] Trade stands as a fundamental driver of economic development and globalization, facilitating the movement of goods and services across borders and fostering interconnectedness on a global scale. Globalization has hastened the interconnection of economies across the globe, heightening the importance of trade as a catalyst for driving economic progress.

Of particular significance are countries endowed with seaports, which function as vital regional hubs for maritime commerce. These ports leverage their strategic positioning to facilitate the seamless movement of goods within the global supply chain, thereby boosting the efficiency and effectiveness of international trade. Against this backdrop, the interplay between trade, globalization, and the proliferation of seaports emphasizes the critical importance of maritime trade in driving economic growth and fostering global connectivity.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD’s) report on Review of Maritime Transport 2022, highlights that a significant majority of global merchandise trade accounting for over 80% is conducted through maritime transportation via the world’s vessel fleet. In recent years, the Port of Mombasa, situated on the Eastern coast of Kenya, has grappled with a series of challenges that have undermined its competitiveness on the global stage such as transportation connectivity, corruption and bureaucracy, infrastructure constraints, security concerns and competition from regional ports among others. In an era characterized by rapid technological advancements and evolving consumer demands, ports must continually adapt and innovate to remain competitive in the face of fierce global competition. The Kenya Kwanza administration, in an effort to revitalize maritime trade, intends to lease the operations and management of five critical ports of Kilindini Harbour, Lamu Port, Kisumu Port, and Shimoni Fisheries Port. This is aimed at enhancing competitiveness along the northern corridor through a Kshs 1.4 trillion public-private partnership (PPP), intended to revitalize the country’s maritime industry.[2]

Recognizing the strategic importance of revitalizing the Port of Mombasa, this brief aims to delve into the underlying issues contributing to its declined competitiveness and propose a comprehensive set of strategies and recommendations to revive its stature as a leading maritime gateway in the East African region.

Background

Historically, the Port of Mombasa has played a pivotal role in promoting trade in East Africa and beyond. As the largest port in Kenya and a key gateway to landlocked countries in the region, including Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, its significance cannot be overstated. However, the port has been encountering a series of challenges that have eroded its competitiveness and hindered its ability to meet the demands of modern maritime trade[3]. The competitiveness of ports is influenced by a multitude of factors including infrastructure, operational efficiency, regulatory frameworks and institutional capacity.

The Port of Mombasa boasts a diverse and expansive infrastructure tailored to meet the demands of modern maritime trade. At its core are the terminals, specialized facilities designed to handle different types of cargo efficiently. These terminals include container terminals for handling containerized cargo, bulk terminals for commodities such as grain and oil, and general cargo terminals for diverse non-containerized goods. Alongside the terminals are berths, where ships dock to load and unload cargo. These berths are equipped with state-of-the-art cranes and handling equipment to facilitate swift and seamless cargo operations.

The third edition of the World Bank report in 2022,on the Global Container Port Performance Index(GCPI), positioned Mombasa port at 326 out of 348 ports assessed worldwide. This marked a significant decline from its previous placement at 296 in the 2021 GCPI report. Conversely, the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam,showed improvement, ranking at 312 compared to its previous position of 361. Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS),in 2022, indicated a decline in cargo volume at the Mombasa port for the first time in five years, attributed to heightened competition from Dar es Salaam.[4] This resulted in a 2.93 percent year-on-year decrease, bringing volumes to their lowest levels since 2018 when they reached 30.92 million tonnes. According to data from KNBS, the total cargo throughput at the port decreased to 33.74 million tonnes in 2022 from 34.76 million tonnes in the previous year. However, by mid-2023, there was a noticeable improvement at the Mombasa port, with smoother cargo flow despite prior congestion issues at the Dar es Salaam and Djibouti ports. According to the Kenya Port Authority’s data, container traffic at the Mombasa port was on course to surpass its annual target of 1.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), having reached 1.32 million TEUs within the first ten months of 2023.[5]

Methodology

This paper is based on qualitative data gathered from maritime experts’ interviews. The data was collected using interview guides which provided in depth discussion on reviving the Mombasa port competitiveness. The primary data was complemented by secondary data from documented sources and analyzed thematically.

Key Findings

This section analyzes key findings leading to port inefficiency, at the Port of Mombasa. The analysis of these key issues is informed by responses from maritime experts and documented literature.

Transport routes connectivity

According to the Shippers Council of East Africa (SCEA) Logistics Performance Survey Report of 2021, which analyzed transport costs in the region, it was revealed that the estimated costs were $1.8 per kilometer per container when using the northern corridor route. The Northern Corridor railway network encompasses the Kenya/Uganda sections, spanning from Mombasa through Nairobi, Nakuru, Eldoret, Malaba, Jinja, and Kampala to Kasese in western Uganda, covering a distance of approximately 1660 km. This contrasts with international best practices, which suggest a cost of $1 per kilometer per container.[6]

The same report reported that the most expensive route for transporting cargo was from Kampala to Mombasa, priced at $2.5 per tonne, followed by the route from Mombasa to Kampala at $2.17 per tonne. Additionally, the transportation cost from Dar es Salaam to Kampala was $1.17 per tonne, while from Bujumbura to Dar es Salaam, it was $1.02 per tonne.

The primary factors influencing freight costs were identified as fuel prices, non-tariff barriers, prolonged clearance times at ports, and slow turnaround times. The report highlighted that Kenya and Uganda recorded the highest frequency of police stops for trucks, ranging between 6-9 stops, whereas Tanzania had 3-5 stops. In contrast, the Central Corridor had streamlined operations by reducing the number of weighbridges from nine to three and minimizing road tolls to enhance overall performance.

Port inefficiency

This section will discuss capacity limitations, port tariffs and workforce dynamics as the key factors leading to port inefficiency. These factors can lead to increased costs, longer turnaround times for vessels, congestion at the port, and ultimately reduced competitiveness in the maritime industry.

1. Capacity Limitations

The port of Mombasa has several capacity limitations including bottlenecks in cargo handling, congestion at terminals, delays in vessel turnaround times, inadequate storage space, and inability to handle larger volumes of cargo. These pressing challenges were underscored in a continental report ‘The Africa’s Port: Fast-tracking Transformation,’ indicating the port’s proximity to reaching full capacity. With its current 19 berths, expansion is limited to Berth 29.[7]

Currently, the Mombasa Port can handle 2.1 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) annually. However, the port handled approximately 1.6 million TEUs in 2023[8]. The Africa’s Port: Fast-tracking Transformation report lists Mombasa alongside Lagos (Nigeria), Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), and Cape Town (South Africa), as among the facilities with infrastructure deficits in the short-term. There is a market of over 385 million people in the Eastern Africa and the unexploited economic opportunities in these countries. Any demand for port facilities beyond berth 29 would necessitate alternative accommodations.

The biggest vessels in the market, such as Maersk Emma, MSC Oscar with capacities nearing 20,000 TEUs, pose a challenge for ports in providing adequate space. Kenya ranked fifth among ports handling the most cargo on the continent, with Mombasa’s average annual throughput standing at 1.6 million TEUs. Egypt’s Alexandria and Port Said led with an average capacity of 6.2 million TEUs, followed by South Africa’s Durban with 4.9 million TEUs, and Morocco’s Tanger Med port with 4.8 million TEUs. Algeria, with approximately 15 ports, occupied the fourth position with an annual handling capacity of 4.8 million TEUs[9]. The inauguration of the Lamu port in 2021 aimed to tap into business from Horn of Africa importers and alleviate congestion at the Mombasa port through trans-shipment. However, data from the Kenya Ports Authority (KPA) indicated that the Lamu port handled fewer than 2000 TEUs, with the Salalah port in Oman being the preferred trans-shipment port. This underperformance was attributed to the underdeveloped connecting roads and planned railways in Lamu, deterring importers from utilizing it.[10]

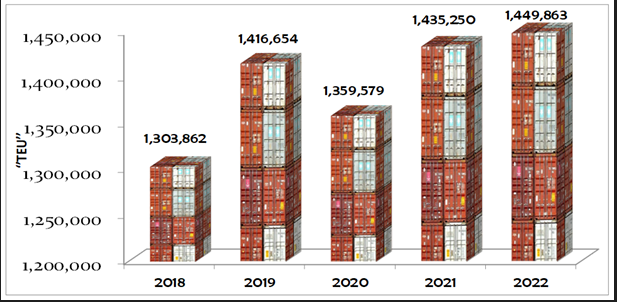

Container Traffic (TEUs): 2018 -2022

The container traffic performance from 2018 to 2022 as reflected in Table 1, shows a positive trajectory. This performance exceeded the set target by 4.5 percent, suggesting that the Port of Mombasa was on track to achieve annual container traffic of 1.48 million TEU by the end of 2023.

2. Port tariffs

Port tariffs pose a significant challenge at the Port of Mombasa, impacting on its competitiveness, financial sustainability, and attractiveness to shipping lines and cargo owners. High port tariffs relative to neighboring ports deter customers from using the Port of Mombasa, leading to a loss of market share and reduced revenue. Data collected from November 2023 indicates that clearing a container from the port of Mombasa is more expensive compared to the Dar es Salaam port, as illustrated in table 2; [11],[12]

| Container type | Kenya($) | Tanzania($) |

| 20ft | 100 | 90 |

| 40ft | 167 | 150 |

Table 2: Container port tarriffs

Excessive port tariffs strain relationships with customers, erode trust hence damaging the port’s reputation. This can be addressed through the landlord port model. In this innovative strategy, the Kenya Ports Authority (KPA) will maintain its role in regulation, strategic planning, and oversight, while operational responsibilities are transferred to private entities. This transition encourages specialization, enhances operational efficiency and facilitates the adoption of modern governance practices. Despite the Kenyan government’s commitment in 2002 to transform Mombasa port into a landlord port, progress in implementation has been slow over the past two decades.

3. Workforce dynamics

Appointment of Managing Director (MD) of KPA, has witnessed the hiring and firing, or resignation of over 10 MDs in the past 16 years, with each MD serving an average of 18 months.[13] It is unrealistic for such an MD to execute meaningful development of the Port on an articulated plan within such short periods. Without consistent leadership, it becomes challenging to sustain progress and implement strategic initiatives that require long-term planning and execution. As a result, the port struggles to address longstanding issues and capitalize on opportunities for growth and improvement.

Ethnicity significantly influences workforce dynamics and skill shortages, particularly when specific ethnic groups dominate the labor market. Challenges related to diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity affect the availability of skilled workers where there is limited access to opportunities for individuals outside of the dominant communities at the port of Mombasa.

A report on ethnic diversity and inclusivity at the Kenya Maritime Authority (KMA) and KPA conducted by a Senate committee on National cohesion, revealed that the Mijikenda community had the highest representation, comprising 25% at KMA and 35% at KPA. This constitutes a violation of the National Cohesion and Integration Act of 2008, which prohibits any single community from occupying more than a third of employment positions in state-owned firms.[14]

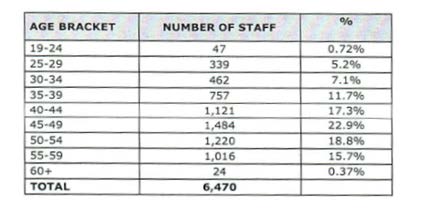

Furthermore, the KPA had a total of six thousand four hundred and seventy (6,470) employees, with five thousand and seventy seven (5077) being male employees and one thousand three hundred and ninety three (1393) being female employees.[15]

An analysis of the age profile of all the 6,470 staff in the authority showed a disproportion in age brackets. The majority of the staff (22.9%) fall within the age bracket of 45 to 49, while those considered youth, aged between 19 and 34, comprise 13.1% of the total staff population, as illustrated in the table below:

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Port of Mombasa faces significant challenges that have hindered its competitiveness in recent years, including transport connectivity, capacity constraints, high port tariffs, and workforce dynamics. These challenges have resulted in declining cargo volumes and reduced efficiency compared to regional counterparts. To address these issues and revitalize the port’s competitiveness, several key recommendations are proposed. They include enforcing merit-based recruitment at the KPA, expediting railway projects to improve rail connectivity, implementing a landlord port model to introduce competition and innovation, fast-tracking infrastructure expansion projects, and initiating tailored mentorship and capacity-building programs. By implementing these recommendations, stakeholders can work towards restoring the Port of Mombasa’s vital role in facilitating regional trade and fostering economic growth in East Africa.

Recommendations

- The Public Service Commission should enforce merit-based recruitment at KPA. This will ensure that selection process rely solely on merit, qualifications, and relevant experience through transparent standardized tests and competency-based interviews.

- The Kenya Railways Corporation (KRC) should expedite the completion of railway projects, such as the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) 2B, to improve rail connectivity between Naivasha to Malaba.

- The Ministry of Roads and Transport and the Kenya Ports Authority should implement a landlord port model, leasing terminal facilities to private operators, thereby introducing competition, innovation, and potentially lower costs for port users.

- The Kenya Ports Authority should fast track the expansion of berth 19B, of the second container terminal which is projected to increase capacity by 400,000 TEUs.

Bibliography

Ali, E., & Ayelign, A. (2022). The impacts of port characteristics and port logistics integration on port performance in Ethiopian dry ports. International Journal of Financial, Accounting, and Management, 4(2), 163-181.

Ansorena, I. L. (2021). On the benchmarking of port performance. A cosine similarity approach. International Journal of Process Management and Benchmarking, 11(1), 101-114.

Baştuğ, S., Haralambides, H., Esmer, S., & Eminoğlu, E. (2022). Port competitiveness: Do container terminal operators and liner shipping companies see eye to eye? Marine Policy, 135, 104866.

Farzadmehr, M., Carlan, V., & Vanelslander, T. (2024). How AI can influence efficiency of port operation specifically ship arrival process: Developing a cost–benefit framework. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 1-28.

Kong, Y., & Liu, J. (2021). Sustainable port cities with coupling coordination and environmental efficiency. Ocean & Coastal Management, 205, 105534.

Kunambi, M. M., & Zheng, H. (2024). Contextual Comparative Analysis of Dar es Salaam and Mombasa Port Performance by Using a Hybrid DEA (CVA) Model. Logistics, 8(1), 2.

Luo, M., Chen, F., & Zhang, J. (2022). Relationships among port competition, cooperation and competitiveness: A literature review. Transport Policy, 118, 1-9.

Nayak, N., Pant, P., Sarmah, S. P., Jenamani, M., & Sinha, D. (2024). A novel Index-based quantification approach for port performance measurement: A case from Indian major ports. Maritime Policy & Management, 51(2), 174-205.

Oyenuga, A., Dooms, M., Sys, C., & Verhoeven, P. (2023, September). Towards a next phase of port reform in Africa: an analysis of context, drivers, performance and options. Paper presented at the International Association of Maritime Economics (IAME) Annual Conference 2023, Sept 5-7, 2023, Long Beach, California, USA: New Realities in the Global Economy.

Saini, M., & Lerher, T. (2024). Assessing the factors impacting shipping container dwell time: A multi-port optimization study. Business: Theory and Practice, 25(1), 51-60.

Notes

[1] ElGanainy, A. A., Hakobyan, S., Liu, F., Weisfeld, H., Allard, C., Balima, H. W., … Pohl, M. M. (2023). Trade Integration in Africa: Unleashing the Continent’s Potential in a Changing World.

[2] https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/president-ruto-revives-plans-to-lease-five-ports-in-sh1-4trn–4255160

[3] Juma, C. T. (2012, November). Perceived challenges of importation through the port of Mombasa faced by countries in the Great Lakes region

[4] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Economic Survey 2022.

[5] https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/mombasa-port-to-beat-performance-target–4447078

[6] https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/northern-corridor-cited-most-costly-in-the-world-3904946

[7] Africa’s Ports: Fast-Tracking Transformation. (2020, October). Africa CEO Forum

[8] Kenya Ports Authority(2023). Press release: Port of Mombasa posts record performance.

[9] Africa’s Ports: Fast-Tracking Transformation. (2020, October). Africa CEO Forum

[10] https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/counties/article/2001433039/lamu-port-signals-good-tidings-despite-slow-growth

[11] https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/cargo-tariffs-set-to-rise-as-agents-set-minimum-fees

[12] Tanzania Ports Authority. (2023, November). Tariff book: Sea ports

[13] Gharib, M. S. G.). There is an ocean of economic opportunities at the Kenyan coast. Unpublished manuscript.

[14] Report on ethnic diversity and inclusivity at the Kenya Maritime Authority(KMA) and Kenya Ports Authority(KPA)

[15] Report on ethnic diversity and inclusivity at the Kenya Maritime Authority(KMA) and Kenya Ports Authority(KPA)