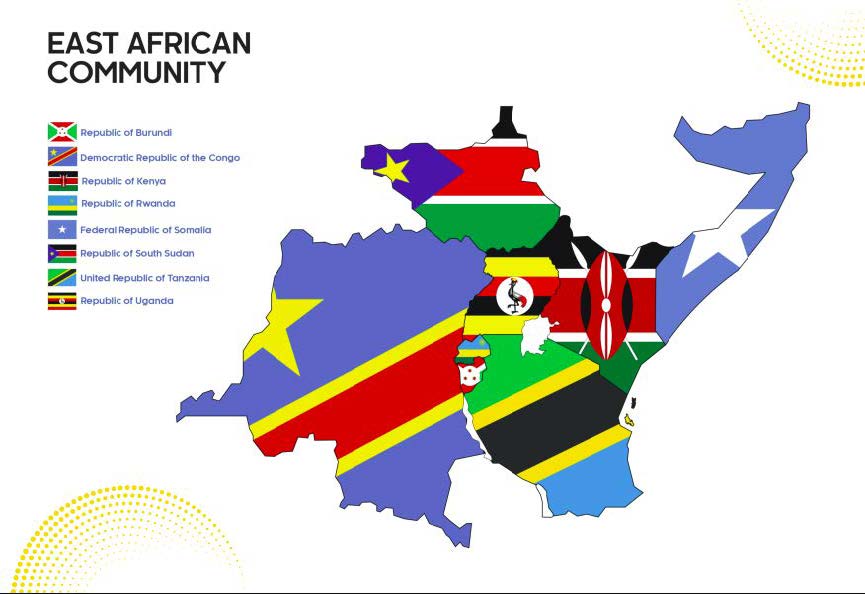

Ethiopia expects to join the East African Community (EAC), as the 9th member of an organization that is expanding both northwards and westwards but not southwards. Ethiopia does not have a northward attraction and is instead geopolitically attracted southwards to Kenya. When admitted, it will be part the EAC’s northward expansion that started with South Sudan which Kenya helped to birth and former irredentist Somalia that Kenya helped to reform and restructure. While Kenya tends to be the centre of geopolitical gravity in Eastern Africa, South Africa tends be that centre in Southern Africa and actually competes with Kenya as a regional magnet. As such, Tanzania finds itself pulled both southwards and eastwards as a founder member of the East African Community. Ethiopia, in contrast, does not face the Tanzanian conflict on which direction to lean on given that there is hostility in the north, in Egypt. It took time for Ethiopia to re-orient its geopolitical interests towards East African Community for two possible and inter-connected reasons that separated it from the others. First, it did not share colonial experiences and subsequent sense of identities. Second, it harbored ambitions of being the centre of geopolitical gravity in Eastern Africa, mainly because of its history and population size. It took time to realize it needed the EAC, not the other way round. This commentary highlights potentials and pitfalls of Ethiopia joining the EAC.

The idea of Eastern Africa regional economic unit has colonial roots, part of the European scramble for Eastern Africa. The imperial competition between Britain, France, and Italy confined equally expanding Ethiopia to its current boundaries as a landlocked country and established modern Kenya, Eritrea, Uganda, Djibouti, and Sudan before the split. Britain and Germany demarcated Tanganyika and Kenya, with Britain acquiring Tanganyika after World War I. With Sudan closely connected to Egypt, Somalia remaining Italian property, while Belgians kept Congo and Rwanda-Urundi, the three British controlled colonies in East Africa gravitated towards each other in commerce and related services. In the 1920s white settlers in Kenya sought ‘closer union’ with Nairobi as the dominion headquarters but the other two rebelled. During World War II, British Minister Ernest Bevin had suggested creating ‘Greater Somalia’ to comprise parts of Ethiopia, Kenya, Italian and British Somaliland but the idea flopped. After World War II, Britain created the ‘East African Common Market Services’ with Nairobi as the headquarters. At independence in the early 1960s, the three colonies united in terms of important and uniting common services such as currency, transport, and postal, but the idea of political federation remained elusive despite its seductive attributes.

While independence culminated in the breakup of the common services, derived from the colonial suspicion of Kenya as a regional mini-exploiter of the rest, the desire to maintain a sense of unity led to the creation of the first East African Community among the three. Ethiopia, despite being a continental point of inspiration for having resisted the Italians at Adowa in 1896, and closeness to Kenya, remained outside. Ideological and personality differences, however, led to the breakup of EAC in 1977 only for new leaders in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania in the 1980s to revive it with some safeguards to avoid previous pitfalls. The unity of purpose for Kenya’s Daniel arap Moi, Uganda’s Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, and Tanzania’s Ali Hassan Mwinyi revived the EAC and made it so vibrant that others started craving to join. First were Rwanda and Burundi, there followed newly created South Sudan, then Congo followed by Somalia and now Ethiopia wants in. The common factor in all the new entrants, other than neighbouring member states, is that each was internally unstable. The assumption was that being in the EAC would help to create internal and regional stability. Since Ethiopia needs both internal and regional stability, membership in the EAC might help.

Ethiopia has lost its initial inspirational role first as winner over the Italians in 1896 at Adowa and second as prompter of Pan-Africanism. The inspiration to Pan-Africanism was the realization that white powers, irrespective of ideology, did not care for black people anywhere. The failure of white powers and the League of Nations to stop Italian aggression on elevated Ethiopia’s role as inspiration point for global blackness. Although it temporarily fell under Italian and British supervision during World War II, it retained its image of independence and was a founder member of the United Nations. Africans accepted its offer of Addis Ababa as the headquarters of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), one of whose main principles was the sanctity of inherited colonial borders and the non-interference in the internal affairs of sister republics.

Instead of remaining as the continental inspiration, however, Ethiopia slid into internal and regional disputes over territories and power and became object of global pity. While internal mainly ideological ‘liberations’, led to the separation of Eritrea which landlocked Ethiopia, ethnic rebellion against Amharic and Tigray dominance made the country unstable. The instability paved the way for the emergence of Ahmed Abiy.His purported MOU with Somaliland in January 2024 over access to the Red Sea has attracted global wrath and has seemingly backfired. Isolated all around, Abiy seeks a geopolitical way out and noticing Somalia’s success in gaining admission to the EAC also seeks admission.

Ethiopia in the EAC portends negative and positive possibilities. The negative include the trans-nationalization and regionalization of Ethiopia’s problems. Ethiopia generates a lot of refugees who theoretically would be free to roam the region. It will add to EAC’s financial burden, given that the EAC depends on ‘donors’ for its operating budget since members rarely honour their pledges. On the positive side, membership in the EAC means an expansion of the regional market to roughly 500 million and would encourage local manufacturers to produce needed goods while reducing imports from extra-continental sources. Ethiopia might also be induced to shelf its ambition in Somalia and instead turn to promoting Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project for both security and commercial reasons. The personal relationship between Ethiopian and Somali leadership under the EAC auspices would improve and lessen tension.

In conclusion, the inclusion of Ethiopia in EAC, just like that of DR Congo and Somalia will change the meaning of EAC as an African regional body. No longer confined to the challenges of the original three British colonies in East Africa, it has the potential of becoming a continental force if those who join embrace the initial EAC spirit that entailed dreams of political federation. It might actually become a serious organ for creation of regional stability by enabling increased regional commerce and free movements of people, goods, and services. While Ethiopia’s presence, with its huge population, will add vigor to the organization, it will need to make cultural and geopolitical adjustments in order not to appear to threaten the rest. EAC might become a new theatre of Ethio-Somali rivalry in the hope that both countries will subject themselves to the interests of the region. Given the seeming new Somali geo-strategy of adapting, integrating, and control is regionally effective, Ethiopia might consider re-adjusting its own regional policies. In the process, Abiy will have to shelve his dreams of surpassing Menelik II’s imperial ambitions of acquiring access to the sea.

Bibliography

Alex de Waal and Mulungeta Gebrehiwat Behr, “Ethiopia Back on the Brink: Abiy’s Reckless Ambition and Emrati Meddling- Are Fueling Chaos in the Horn,” Foreign Affairs, April 2024

Harold G. Marcus, “The Foreign Policy of the Emperor Menelik 1896-1898: a Rejoinder,” Journal of African History, Volume 7, No. 1, 1966, pp. 117-122

Judy Njeru, Pontian Okoth, and Frank K. Matanga, “Political Factors Influencing Integration in the East African Community (EAC) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Bloc,” Journal of Education and Research, Volume 6, No. 8, August 2018, pp. 211-224

Luke Anami, “Kenyatta’s EAC agenda: Admit more countries to regional bloc,” The East African, September 6, 2021

Macharia Munene, “Abiy’s unbridled ambitions stoking tensions in neighbouring countries,” The Standard, Monday, January 15, 2024

Macharia Munene, “Conflict and Postcolonial Identities in East/Horn of Africa,” in K. Omeje, editor, The Crisis of Postcoloniality in Africa (Dakar, Senegal: CODESSRIA Books, 2015), pp.123-142.

Macharia Munene, “Geopolitical Dynamics in the Horn of Africa Region,” The Horn Bulletin, Volume V, Issue 1, January-February, 2022, pp. 1-11

Martija Seric, “Kenya: A Regional Power in Africa and the Indo-Pacific-Analysis,” eurasiareview: news & analysis, April 24, 2024

Musinguzi Blanshe, “East Africa: Geopolitics and self-interest stifle ambitions for economic integration,” The Africa Report, February 6, 2024

Mvemba Pheso Dizolele, “State Of Eight: Challenges Facing The East African Community,” Transcript of Into Africa Podcast, (CSIS: Center for Strategic & International Studies, April 4, 2024).

Namha Thando Matshanda, “Ethiopia’s Civil War: Postcolonial modernity and the violence of contested national belonging,” Nations and Nationalism Volume 28, Issue 4, 2022, pp. 1282-1295

Nic Cheeseman and Yohanness Woldemariam, “Abiy Ahmed Crisis of Legitimacy: War and Ethnic Discrimination Could be the Ethiopian Prime Minister’s Undoing,” Foreign Affairs, December 30, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/2020-12-30/abiy-ahmeds-crisi-legitimacy

Nigusu Adem Yimer and Hailu Gelana Erko, “ Middle East: State Rivalry in the Horn of Africa. Key Drives, Geopolitical Implications, and Security Challenges,” Conflict Studies Quarterly July 2023, pp. 78-97

Paulo Santos, Geopolitical Imperatives of Ethiopia’s Quest for Red Sea Access: A Historical and Strategic Analysis,” Ethiopian Institute for Strategic Studies, October 2023

Robert Klosowicz, “The role of Ethiopia in the regional security complex of the Horn of Africa,” Ethiop.j.soc.lang.stud 2(2), 2015, pp.83-97

Sankalp Gurjah, “Ethiopia-Somaliland Port Deal and Geopolitics of Western Indian Ocean-Analysis,” Geopolitical Monitor.com January 9, 2024

Tafi Mhaka, “Abiy Ahmed’s imperial ambitions are bad for Africa, and the world,” Al-Jazeerah Opinion, November 14, 2023

Thomas Otieno Juma, “Amity and Enmity of Regional Integration; the East African Communty (EAC) Experience,” International Journal of World Policy and Development Studies, Volume 8, Issue 2, 2022, pp.57-65

Walter Oyugi and Jimmy Ochieng, “East Africa Regional Politics and Dynamics,”June25,2019 https://oxfordre.com/politics/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228673.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228

Yirga Abebe, “Contemporary Geopolitical Dynamics in the Horn of Africa: Challenges and Prospects for Ethiopia,” International Relations and Diplomacy,” September 2021, Volume 9, No. 09, pp.361-371