1.0 Introduction

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), established in 2000, is a platform designed to strengthen diplomatic, economic, and developmental ties between China and African nations.[1] It focuses on key areas such as infrastructure development, trade, investment, and financial cooperation. A notable example of its impact in East Africa is China’s investment in major infrastructure projects like the Kampala-Entebbe Expressway and the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR). These projects underscore FOCAC’s role in enhancing regional connectivity and economic growth. Between 2010 and 2015, China also extended significant financial aid to the region, committing about US$7.3 billion to various East African countries, with Kenya and Uganda being the largest beneficiaries from 2015 to 2020.[2]

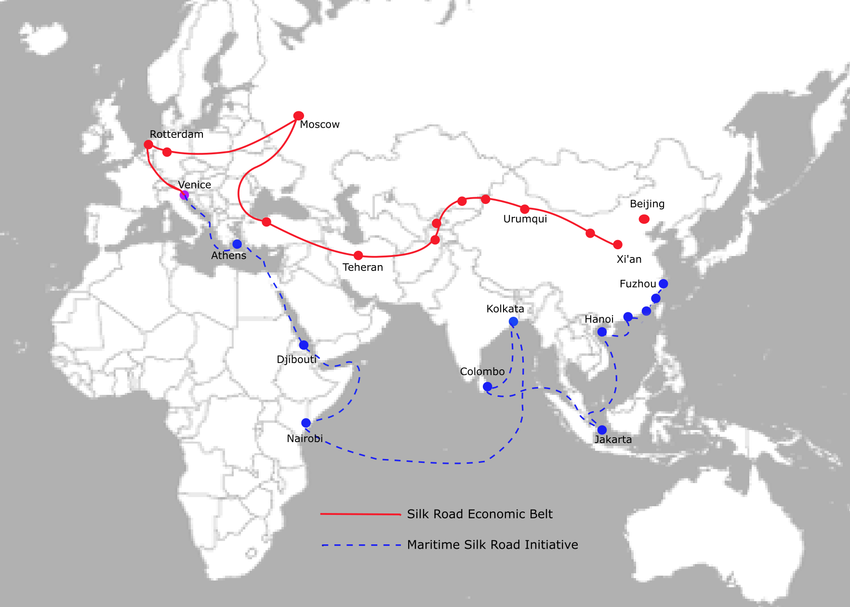

Despite the aforementioned achievements, claims of corruption and mismanagement of these developmental loans still persist. For instance, the Kenya SGR has been highlighted as a mega source of corruption and it has been reported to have been linked to massive irregularities and fraud, including a possible overpayment of KES 777 billion.[3] This was reported to be the third highest value of tainted ventures being implemented globally under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[4] Additionally, corruption has been linked to Chinese funded projects in Uganda specifically the upgrade of the Entebbe International Airport, with findings suggesting that the US$200 million award breached Uganda’s Public Procurement and Disposal of Public (PPDPA) Assets Act.[5] Further, the renegotiated Sicomines mining deal between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Chinese investors has also brought corruption and financial irregularities concerns at the fore.[6] According to a 2017 report by the US-based NGO Carter Center, Sicomines consortium was unable to account for about USD 685 million out of about USD 1.16 billion that had been allocated for infrastructure spending by that time.[7] Moreover, the DRC state Auditor, the Inspector General of Finances, reported in February 2023 that only USD 822 million out of the promised USD 3 billion had been invested in the infrastructure since the agreement’s inception.[8] Such governance challenges not only undermine the benefits of these foreign projects but also cast a shadow over the effectiveness of Chinese development initiatives in the region.

This commentary therefore seeks to review how East African countries can boost transparency and improve governance to better realize the benefits of future FOCAC financial commitments, especially in light of China’s recent pledge of $50 billion in financing over the next three years. The discussion will address institutional strengthening, transparent procurement, and public participation, with actionable recommendations at the end on how to maximize the potential of FOCAC investments.

2.0 Key Issues

2.1 Institutional strengthening and independence

Political interference greatly undermines the potential of institutions in East Africa to effectively manage foreign funds. To ensure value for money from FOCAC investments, respective governments should focus on enhancing the capacity of key institutions that will support these investments, including finance ministries, project management offices, and public procurement agencies. By ensuring these bodies operate with independence, they can make impartial, transparent decisions that secure value for money. For instance, Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway project, built at a cost of about USD 3.2 billion, has attracted criticism for insufficient disclosure of decision-making and skepticism about its economic viability.[9] Independence of an entity such as the Kenya Railways Corporation would have reduced public skepticism and furthered the success of the project.

By contrast, Rwanda has given the continent a good example, investing a lot in strong institutional governance, reflected in various high rankings on the World Bank’s Governance Indicators.[10] This is partly because of the establishment of autonomous oversight entities-for example, the Rwanda Public Procurement Authority, which ensures that tendering procedures for government contracts are competitive and transparent. Moreover, Rwanda’s relative success in combating corruption and enhancing regulatory quality offers the rest of the East African countries valuable lessons on ways of maximizing investment benefits through FOCAC. Its strength in this area demonstrates how strong governance can assure foreign investment payoffs while minimizing the risks of mismanagement.

Strengthening independent auditing bodies is crucial for improving governance and ensuring accountability in the oversight of FOCAC-funded projects. These establishments, including Kenya’s Office of the Auditor-General, are vital in monitoring public expenditure but often face significant resource and capacity constraints. Enhancing their autonomy, increasing funding, and providing legal protections could help them conduct more rigorous audits. However, a persistent challenge in East Africa has been policy inactions following corruption allegations and accountability failures. For instance, independent audits in Uganda have repeatedly uncovered systemic mismanagement of Chinese-funded road projects, resulting in significant financial losses. Despite these findings, limited corrective measures have been implemented. Strengthening the capacity of Uganda’s Inspectorate of Government, coupled with decisive actions on audit outcomes, is necessary to ensure better value for money from Chinese investments and foster sustainable infrastructure development.

2.2 Enhancing transparent procurement procedures and contracting practices

The opacity of procurement processes and contract negotiations is another major concern with FOCAC-funded projects in East Africa. This can drive up project costs, corruption, and partiality, weakening the benefit of the foreign financial assistance. Infrastructure deals involving Chinese firms have attracted public controversy in Kenya, Uganda, and DRC because of the non-disclosure of the terms surrounding these projects, resulting in increased suspicion over the fairness of loan conditions and repayment schedules. The secrecy in these contracts has made the public and civil society organizations question whether they serve the long-term interests of the country or are skewed toward foreign contractors or particular political elites.

For East African countries to fully benefit from FOCAC financial assistance, procurement and contracting processes must be transparent, competitive, and in line with legal frameworks such as the Public Procurement and Disposal Act and Public Procurement Regulations of 2020. While government bodies like the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA) play a critical role in overseeing these processes, there have been concerns regarding the extent to which they are bypassed. These complaints often point to irregularities, lack of adherence to guidelines, and opaque contracting procedures.[11] PPRA reports submitted to parliament highlight these gaps, emphasizing challenges in enforcing procurement regulations. Likewise, parliament’s Public Accounts Committee (PAC), tasked with scrutinizing public expenditure, need to be empowered to effectively perform its role by addressing issues flagged by procurement audits. Strengthening oversight mechanisms, ensuring adherence to procurement laws and bolstering the capacity of regulatory bodies is also vital to enhancing transparency. By doing so, governments can foster trust, ensure accountability, and better leverage foreign loans for the benefit of East African populations.

2.3 Fostering public participation

Public participation in project planning and implementation is crucial in foreign-funded projects as it ensures openness and accountability. The SGR project in Kenya for example encountered criticism and protests due to limited public engagement, especially at the environmental and land compensation stages.[12] For instance, the route through Nairobi National Park was opposed by environmentalists due to probable damage to natural habitats; sparking protests and calls to have it changed. This public outcry led to a refined design that included raising parts of the railway to allow animals to cross and the inclusion of water points along the route. This shows that early involvement of the public during the planning phase is an indispensable step to help flag environmental and social concerns. Therefore there is need for enhanced consultations with local communities, experts in environmental matters, and civil society to prevent potential conflict and make sure projects are in line with broad public interest. Moreover, the lack of participation of the general public may further worsen socio-economic problems, such as land compensations as seen in the case of SGR. Compensation for the acquisition of land for the project was characterized by delays and controversy for most local communities, citing corruption and manipulation as the key cause. If public consultations had been more effective, such issues could have been addressed in a more transparent manner. The overdependence on the centralized decision-making system by most EA countries without the involvement of the public and the community often leads to mistrust and loss of public confidence in externally-funded projects.

While most EA states have provision for legal frameworks for public participation in project planning, challenges persist such as weak enforcement, corruption, lack of awareness, and logistical issues. Therefore, there is need for governments to set up independent oversight bodies to enforce the law on consultations, transparency, and penalties. Moreover, investing in civic education and capacity building in project affected communities is crucial to raise awareness and logistical support for inclusive and effective engagement.

3.0 Conclusion

Good governance and transparency would play a key role in maximizing the benefits from FOCAC investments by East African countries. Whereas Chinese funding has been significant in supporting regional infrastructural development, corruption, weak institutional capacity, and lack of transparency have reduced the potential impact of these projects. Therefore, there is need for strengthening institutional independence, empowering auditing bodies, and ensuring that procurement processes are transparent. Meaningful public participation in the planning and implementation of projects will also help address socio-economic and environmental concerns, leading to greater public trust and acceptance. By fully addressing the highlighted structural challenges, EA states can better catalyze and leverage the financial support accorded by FOCAC to promote sustainable development and economic growth.

4.0 Recommendations

To address specific challenges, countries like Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania should adopt tailored approaches to improve governance and transparency in FOCAC-funded projects.

Kenya needs to reinforce the independence of institutions such as the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA) and the Kenya Railways Corporation (KRC). This will ensure procurement processes for large-scale projects like the SGR strictly adhere to the Public Procurement and Disposal Act. The government should also enhance the oversight role of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) in the National Assembly to scrutinize FOCAC-funded projects. Regular reporting of audit findings and corrective measures to the public will foster trust and transparency.

In Uganda, where mismanagement of FOCAC-funded projects has been recurrent, the Inspectorate of Government should be bolstered through increased funding, autonomy, and enforcement capacity. The country should prioritize improving adherence to the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets (PPDPA) Act by enforcing strict procurement regulations and ensuring that breaches—like those in the Entebbe Airport upgrade—are addressed swiftly. Public disclosure of the terms of Chinese loans and agreements will also reduce the opacity that fuels corruption.

Tanzania can enhance its procurement processes by ensuring that regulatory frameworks like the Public Procurement Regulations of 2020 are rigorously implemented. Strengthening institutions like the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA) and enhancing the accountability of procurement officers involved in Chinese-funded projects will be crucial. Moreover, the country should invest in public participation mechanisms to address concerns related to land acquisition, compensation, and environmental impacts; learning from Kenya’s SGR experience.

Across all three countries, a combination of institutional strengthening, legal enforcement, and public engagement will help mitigate corruption risks and ensure FOCAC-funded projects genuinely contribute to sustainable development.

5.0 References

[1] Origin, Achievements, and Prospects of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. Retrieved from:

http://www.focac.org/eng/lhyj_1/yjcg/201810/P020210830627854979477.pdf

[2] Chinese lending to East Africa: What the numbers tell us. Development Initiatives, 2022. Retrieved from:

https://devinit.org/resources/chinese-lending-to-east-africa-what-the-numbers-tell-us

[3] Ex-government auditor alleges massive irregularities and fraud in SGR funding. Okoa Mombasa, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.okoamombasa.org/en/news/massive-irregularities-fraud-sgr-funding/

[4] Sh394bn of China funded projects linked to graft. Business Daily, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/sh394bn-of-china-funded-projects-linked-to-graft-3590450

[5] Chinese infrastructure development in Uganda: triumphs and trials. Development Policy Centre, 2024. Retrieved from: https://devpolicy.org/chinese-infrastructure-development-in-uganda-triumphs-and-trials/

[6] Uncertainties Remain With Renegotiated Chinese Mining Deal in DRC. Voice of America (VOA), 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.voanews.com/a/uncertainties-remain-with-renegotiated-chinese-mining-deal-in-drc-/7458908.html

[7] A State Affair: Privatizing Congo’s Copper Sector. The Carter Center, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/democracy/congo-report-carter-center-nov-2017.pdf

[8] Long road for DRC as it renegotiates minerals deal with China. Radio France Internationale (RFI), 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20230812-long-road-for-drc-as-it-renegotiates-minerals-deal-with-china

[9] Cost of China-built Railway Haunts Kenya. Voice of America (VOA), 2020. Retrieved from:

https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_cost-china-built-railway-haunts-kenya/6184880.html

[10] What makes Rwanda one of least corrupted countries in Africa? Xinhua, 2019. Retrieved from: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-12/10/c_138621002.htm

[11] An evaluation of corruption in public procurement. A Kenyan experience. Retrieved from: https://eacc.go.ke/default/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Evaluation-of-corruption-in-the-public-procurement.pdf

[12] China-Driven Rail Development: Lessons from Kenya and Indonesia. South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), 2022. Retrieved from: https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Policy-Insights-121-otele-lim-alves.pdf