1.0 Introduction

The escalating situation in the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) since late January 2025 with the M23 group taking over key towns including the regional capital Goma presents grave security concerns to the region and indeed complicates the peace dynamics in the Great Lakes Region. This recent crisis has once again escalated tensions between Rwanda and DRC. As regional and international actors such as the United Nations, the African Union, the Eastern African Community, the South African Development Community continue to find a way out of the crisis using diplomatic channels, reflecting on longer term interventions remain critical to address the protracted security situation in this region. The region is home to multiple armed non-state actors numbering over 140 including the M23. In the immediate term, building trust levels between the governments of Rwanda and the DRC, addressing the growing humanitarian crisis remain paramount. In the medium term, calibrating the mandates of regional mechanisms such as the SAMIDRC, commitments to the Luanda and the Nairobi processes, while prioritizing security sector reforms remains pivotal in the pursuit of sustainable peace in the eastern DRC.

1.1 Introduction and Context

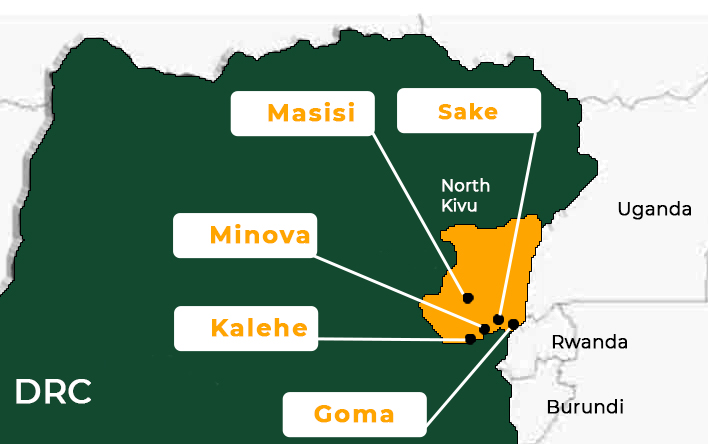

On Sunday 26th of January 2025, The March 23 movement, better known as M23 mounted an offensive on Goma, the regional capital of the Eastern DRC, North Kivu province. The group has in recent months occupied other towns in the eastern region including Katale Masisi, Minova and Sake. This unfolding situation has triggered a humanitarian crisis, creating massive displacement estimated at slightly over 400,000, loss of lives and livelihoods. In addition, it has reopened tensions between Rwanda and the DRC that could escalate into a full blown regional war if the situation is not rapidly deescalated. This could be akin to a regional war that was experienced between 1996 and 2003, with Uganda and Rwanda having been heavily involved in the conflict. These were tied to their regional security interests.

The African Union Peace and Security Council (PSC) held an emergency ministerial meeting on 28th January 2024 on the situation and expressed grave concerns on the evolving situation. The PSC in this meeting resolved to send a fact finding mission, called for a de-escalation of the tensions between Rwanda and DRC through peaceful means. The AU PSC in its communiqué further calls for the implementation of the August 2024 Ceasefire Agreement and the “Harmonized Plan for the Neutralization of FDLR and their Disengagement” of November 2024, adopted under the auspices of the Luanda Process, in addition to a return of the Nairobi process.[1]

The East African Community Head of State Summit convened on 29th January with President William Ruto of Kenya chairing to discuss the crisis in the eastern DRC[2]. DRC did not participate in the Summit. The meeting called for among others the peaceful settlement of the conflict in the DRC including a call for the DRC government to engage with stakeholders in the conflict including the M23.[3] Similarly the United Nations Security Council convened for a third time on the 28th of January 2025 to discuss the Eastern DRC situation. Multiple speakers emphasized among others the need for a ceasefire, including a call for a withdrawal of Rwandan troops in the DRC territory as well as the dismantling of the FDRL armed group[4].

This crisis has seen casualties from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (SAMIDRC) and the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) troops with Tanzania, Malawi and South Africa, and Uruguay incurring losses in their counter-offensive. SAMIDRC replaced the EAC Regional Force from November 2022 to December 2023. Other tensions have related to attacks on diplomatic posts in the Capital Kinshasa in complete violations of the Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic Relations. In the latest escalation, the French Embassy in Kinshasa was set alight, with Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Belgium and US embassies being targeted[5].

1.2 Complex Security Environment

This latest offensive by the M23 further complicates the security situation in the Eastern side of DRC, a context marked by over 100 armed groups including the Allied Defense Forces (ADF) that operates on the Uganda- Congo borderlands. Other actors in this conflict include the FDRL. For context, M23 which is alleged to receive backing from Rwanda[6] with numerous reports from the UN On the same with Rwanda vehemently denies those claims. M23 was formed in 2012 after the breakdown of a previous accord signed in 2009 between the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), a Tutsi-led rebel group, and the DRC government to stop a revolt led by the Tutsi people in eastern DRC. Key to this agreement among others was the integration of the Tutsi group to the DRC national army as a way to secure her people interests. M23 in her formation claimed its objective of safeguarding the ‘Congolese’ Tutsi against the Hutu rebel group that fled to Congo in the aftermath of the Rwandan Genocide (FDRL).

Analyzing the evolving situation in the eastern DRC immediately invokes the post-1994 genocide against the Tutsi in 1994. In 1994 when the then Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) stopped the genocide and assumed power, they pushed the ‘genocidaires’ out to the Eastern DRC. Rwanda has been keen to safeguard her national security interests by pre-empting threats from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDRL). Moreover, DRC is concerned by violations of her territorial integrity and sovereignty with the presence of numerous armed groups, regional and international actors who operate proxy groups in the Eastern side. The DRC owing to multiple state weaknesses that have been systematic due to her unique history characterized by poor leadership and dictatorships such as the Mobutu regime, and numerous proxy actors owing to her extensive natural resources. These resources are at the heart of the conflicts in the eastern DRC.

1.3 Regional Efforts

Regional actors including the African Union, the Eastern Africa Community, the Southern Africa Development Community, the UN, as well as bilateral actors such as Kenya, and Angola have over the years made efforts to address the perennial crisis in this region. Notably two recent interventions such as the Luanda Process that commenced under the leadership of Angola in 2022 with a goal to defuse tensions between Rwanda and DRC. The DRC accuses Rwanda of fighting alongside the M23 rebel whereas Rwanda accuses the DRC of supporting the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) – a Hutu rebel group active in eastern DRC. The Luanda process was relaunched in 2024, with a ceasefire agreed by 30th July 2024. A meeting held in Rubavu in Rwanda bringing Rwanda and DRC intelligence chiefs elaborated on several key themes including neutralizing the FDRL and the withdrawal of Rwandan forces in the DRC. The complexities around the implementation of the Rubavu agreement and by extension the Luanda process also have to account for the DRC mobilization of the Mai Mai armed groups who operate under the Wazalendo group to counter the M23. [7]

1.4 Proposed Interventions to Deescalate the Tensions

There are several interventions that should be taken if this current situation is to be deescalated.

- Open dialogue channels between the governments of Rwanda and DRC to deescalate the situation.

- Addressing the evolving humanitarian situation in the eastern DRC even as a negotiated settlement to the crisis is ongoing.

- The resumption of the EAC Nairobi process remains paramount. This process that commenced in April 2022 had two dimensions; dialogue and the military approach. The dialogue envisaged engaging with armed groups and the DRC government to understand the latter grievances. The military approach would include the voluntary displacement of armed groups as well as the repatriation of non-Congolese armed groups to their state of origin post disarmament.[8]

- Immediately enhance the mandate of SAMIDRC to include the neutralization of the FDRL and the containing of the M23.

- The DRC government should embark on a formulating a ceasefire with the M23 rebel group and its ally the AFC (Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC).

- Long term support by the international community and regional actors in security sector reforms particularly in strengthening the DRC National Army

- Long term regional dialogue on addressing citizenship and identity questions that are at the root cause of the conflict in the eastern DRC.

2.0 Notes

[1] https://papsrepository.africa-union.org/handle/123456789/2271

[2] https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/ruto-calls-urgent-eac-meeting-as-congo-conflict-worsens-4903292

[3] https://www.eac.int/communique/3291-communiqu%C3%A9-of-the-24th-extra-ordinary-summit-of-the-east-african-community-heads-of-state

[4] https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/01/1159511

[5] https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/fighting-rages-in-congo-s-goma-while-embassies-attacked-in-capital-4904422

[6] https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20250129-dr-congo-and-rwanda-leaders-in-crisis-talks-as-m23-rebels-on-brink-of-seizing-goma

[7] https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-revived-luanda-process-inching-towards-peace-in-east-drc